On Jan. 3, after a mass exodus of evicted tenants, many of whom had been living without running water for months, Avista shut off power to Syringa Mobile Home Park. The park is closed and everyone made it out safely, but our work is not over.

After several years getting to know Syringa residents in the context of their ongoing sewage and water problems, I tried to advocate for them when the park's closure was announced. No county or city plans existed to handle this kind of mass relocation. UI Legal Aid Clinic's class action lawsuit exposed the park owner's refusal to maintain a properly functioning sewage and water infrastructure. Even so, comments around town tended to cast blame on Syringa residents.

Most Syringa households survived on limited incomes - working low-wage service jobs, running small businesses on a shoestring or living on Social Security. Residents had the privacy of a mobile home, with lot rent of $275 a month. How does a family wrap its head around paying at least twice that much to rent a two-bedroom apartment in Moscow? Several families lived in Syringa for decades. Nestled in the idyllic Palouse countryside, with a million-dollar view of Moscow Mountain, Syringa was home. It provided a sense of community for people who otherwise felt invisible when they went to Moscow to work and spend their hard-earned money.

In my view, we failed our neighbors in Syringa. Over and over I heard or read there was nothing local, elected leaders could do. Their hands were tied. Instead, private community members and organizations did what we could to help, without government leadership. Syringa residents helped each other. This effort could be interpreted romantically, as an example of what good-hearted communities do. But, leaving it to disparate entities to coordinate a response to such a crisis is impractical, especially when the emergency was clear and inevitable. Residents were stressed, yet didn't seek hand-outs - they needed their elected representatives to offer help, to utilize their community networks, to present options, to advocate. They needed kindness. We need to craft a blueprint soon, and collaboratively, for emergency relocation responses in the future.

Who helped? Sojourners' Alliance Executive Director Steve Bonnar was instrumental. Tyler Williams of Idaho Department of Health and Welfare and Katti Carlson of Family Promise of the Palouse met with families with children. Lysa Salsbury, director of UI Women's Center, and Moscow City Councilor Anne Zabala helped me raise over $13,000 to fill gaps not covered with federal homelessness prevention funds. The Unitarian Universalist Church of the Palouse contributed and raised over $4,000 of this. Sojourners' staff - Cliff McAleer, Rebecca Rucker and Janna Jones - allocated private and federal funds.

UI sociology majors Cynthia Ballesteros and Denessy Rodriguez interviewed residents and organized events. Helping individual residents pack and move were Graham Stevens with sons Sam and Daniel; Tom Lamar; B.J. and Cliff Swanson; Chris Norden; Andy Carman, daughter Stella and friends from Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints; Dave McGraw; Brian Alexander Points; Tellan Lloyd; and Finan Bryan. Russell Paul moved heavy structures. Paul Kimmel organized Avista's donation of two portable toilets to Syringa residents after water was shut off in June. Latah County Sheriff Richie Skiles looked after residents' safety with humane care and sensitivity. Views expressed in this op-ed are my own.

Syringa is our community's canary-in-the-coal-mine, exposing the undeniable fact that housing insecurity is prevalent and whole communities are at risk. There are a lot of talented and experienced people in this region. Are you willing to help plan for future housing emergencies and affordable housing solutions?

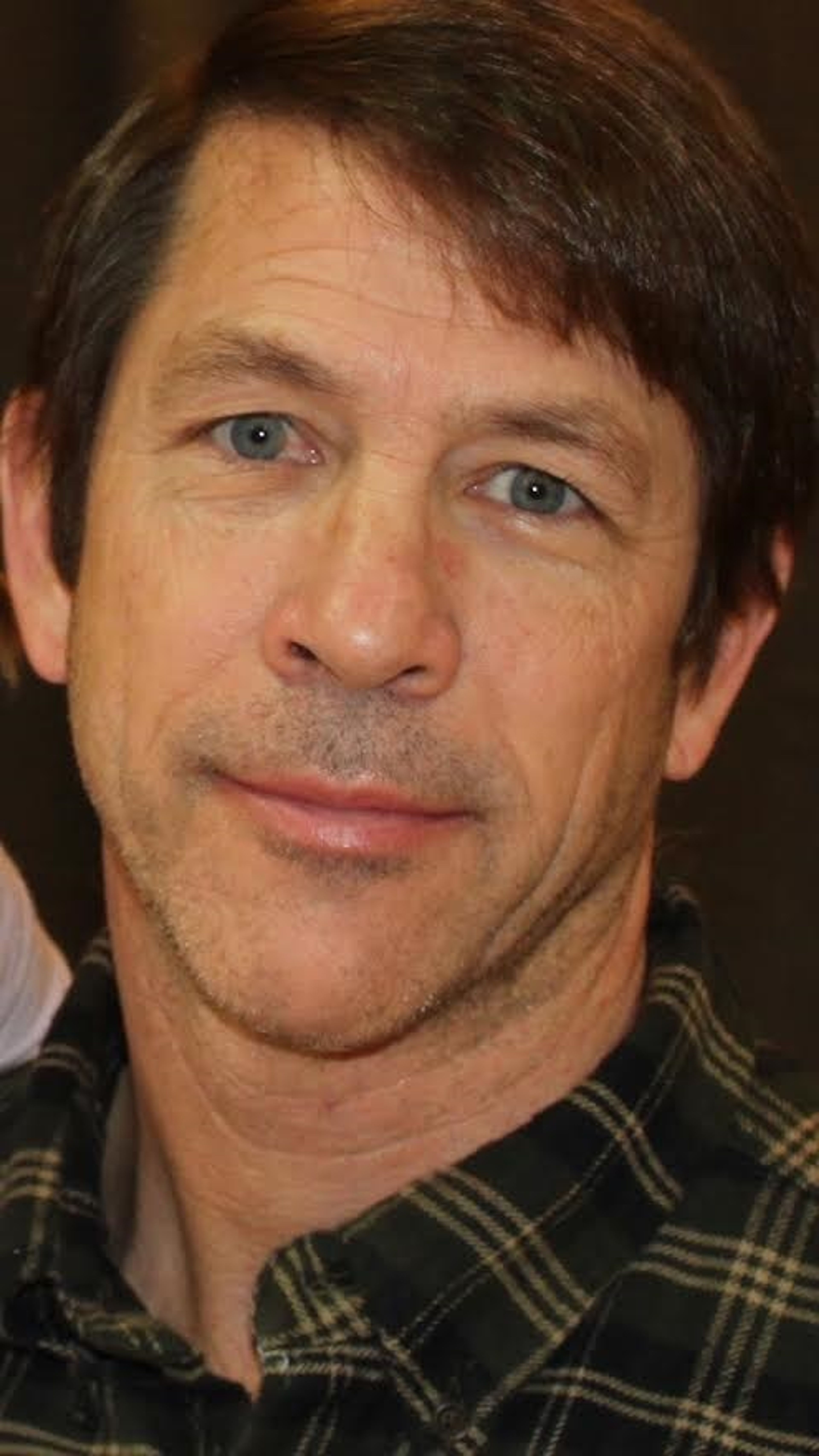

Leontina Hormel is a professor and the director of the Women's, Gender and Sexuality Studies Program at the University of Idaho.