In 1976, as a way of celebrating our nation's bicentennial, I published an article on the religious views of our founding thinkers. I was inspired to write this piece when I heard on the radio that Teddy Roosevelt had called Thomas Paine "a dirty little atheist." I have continued my research by extending it to our 16th president.

Abraham Lincoln never mentions the name of Christ in his writings, and when he was asked if he was a Christian, he refused to answer. When Willam Herndon drafted a speech for Lincoln, the president asked him to replace the word "God" with "Providence," because the former word implied a personal deity.

There is a story that when news of Lee's surrender reached the White House, Lincoln and his cabinet all knelt spontaneously in tearful prayer. Lincoln's treasury secretary, Hugh McCullough, later testified this claim was "not only absolutely groundless but absurd."

Jesse Fell, a close friend and Republican leader, once stated Lincoln did not believe in "the innate depravity of man, the Atonement, the infallibility of the written revelation, the performance of miracles, or future rewards and punishments."

Other sources indicate Lincoln did not believe in the deity of Christ or in the special creation of human beings. He was especially critical of the idea that God forgives sins, because that doctrine would undermine the idea that moral laws are absolute. Jesse Fell explained that Lincoln "maintained that law and order, not their violation or suspension, are the appointed means by which Providence is exercised."

Lincoln adhered firmly to the Doctrine of Necessity and scholars believe this fatalism came from his parent's belief in predestination, a belief so extreme their church did not believe in missionary work.

When Lincoln ran for a seat in the Illinois state Legislature, he was accused of being an infidel and of calling Jesus an illegitimate child. At that time, Lincoln refused to respond to these charges.

When he ran for Congress in 1846, his opponent, the Rev. Peter Cartwright, raised the same issues. This time Lincoln did answer by saying it was true he was not a member of any church, but it was not correct he denied the truth of the Bible.

This statement did not take care of the problem, because when he ran for president in 1860, all the ministers but three in his hometown opposed his candidacy.

After receiving a Bible from some former slaves grateful for their emancipation, Lincoln wrote to them saying: "All the good the Saviour gave to the world was communicated through this book. But for it we could not know right from wrong."

This statement is consonant with the first American presidents, who defined Christianity as, first and foremost, a religion of morality. As John Adams once said: "I believe that all honest men are Christians."

Some scholars have proposed Lincoln's religious views changed with the death of his son Willie and the carnage of the Civil War. The suggestion is Lincoln came to believe God intervened in history to eliminate slavery and to punish both the North and the South for their sins. The further claim that Lincoln also became a Christian at this time is most likely untrue.

It is clear Lincoln was a religious liberal in the original meaning of the Latin word liberalis, "pertaining to the free person." A liberal society would always protect the freedom of its citizens to form their own religious beliefs or reject religion altogether if that is their choice.

James Madison summed up this religious liberalism in this concise motto: "Conscience is the most sacred of all property."

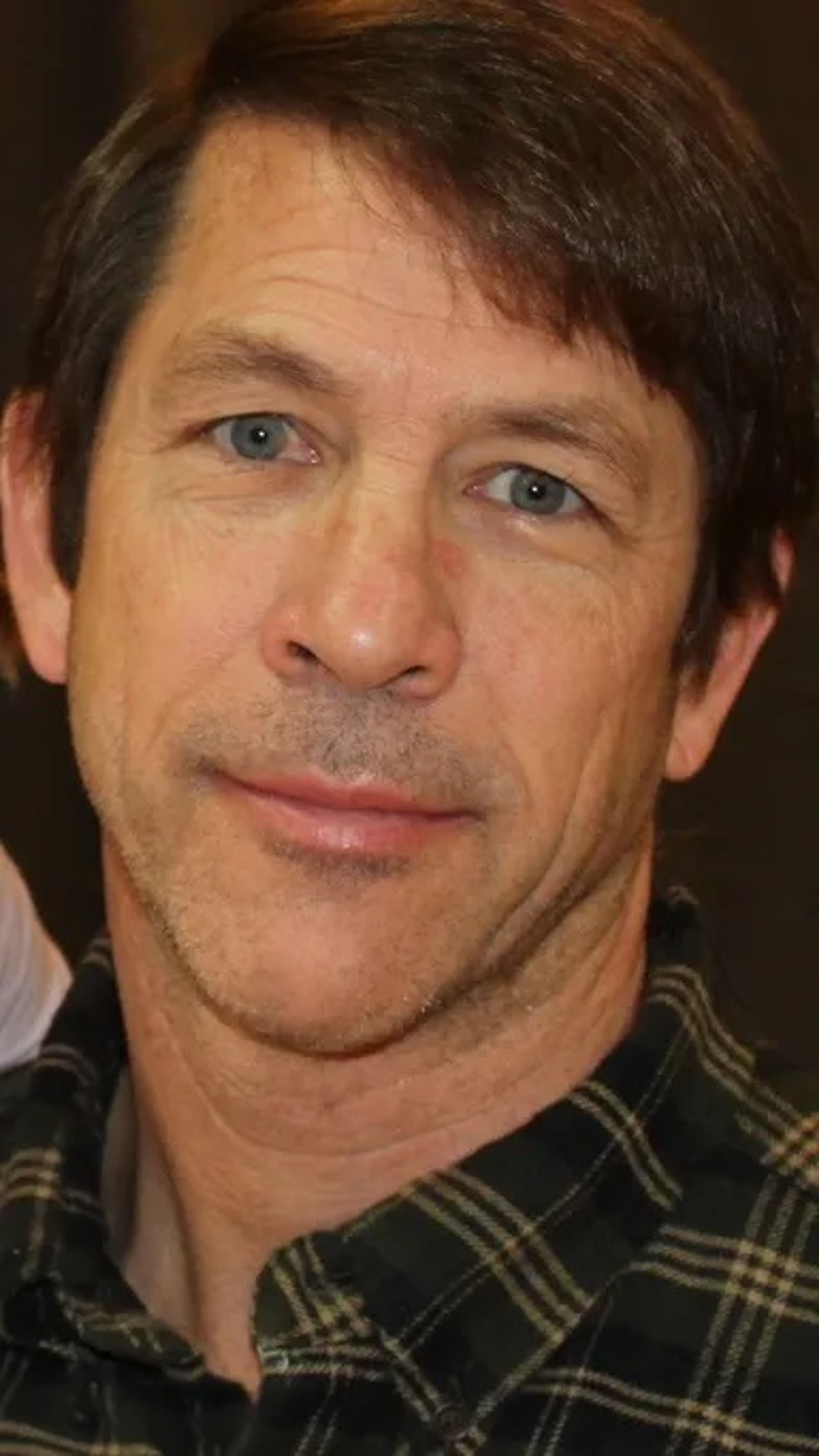

Nick Gier taught religion and philosophy at the University of Idaho for 31 years. His article on the religious views of our founding thinkers is at webpages.uidaho.edu/ngier/foundfathers.htm. He can be reached at ngier006@gmail.com.