School closings threaten gains of students with disabilities

Without any in-school special education services for months, 14-year-old Joshua Nazzaro’s normally sweet demeanor has sometimes given way to aggressive meltdowns that had been under control before the pandemic.

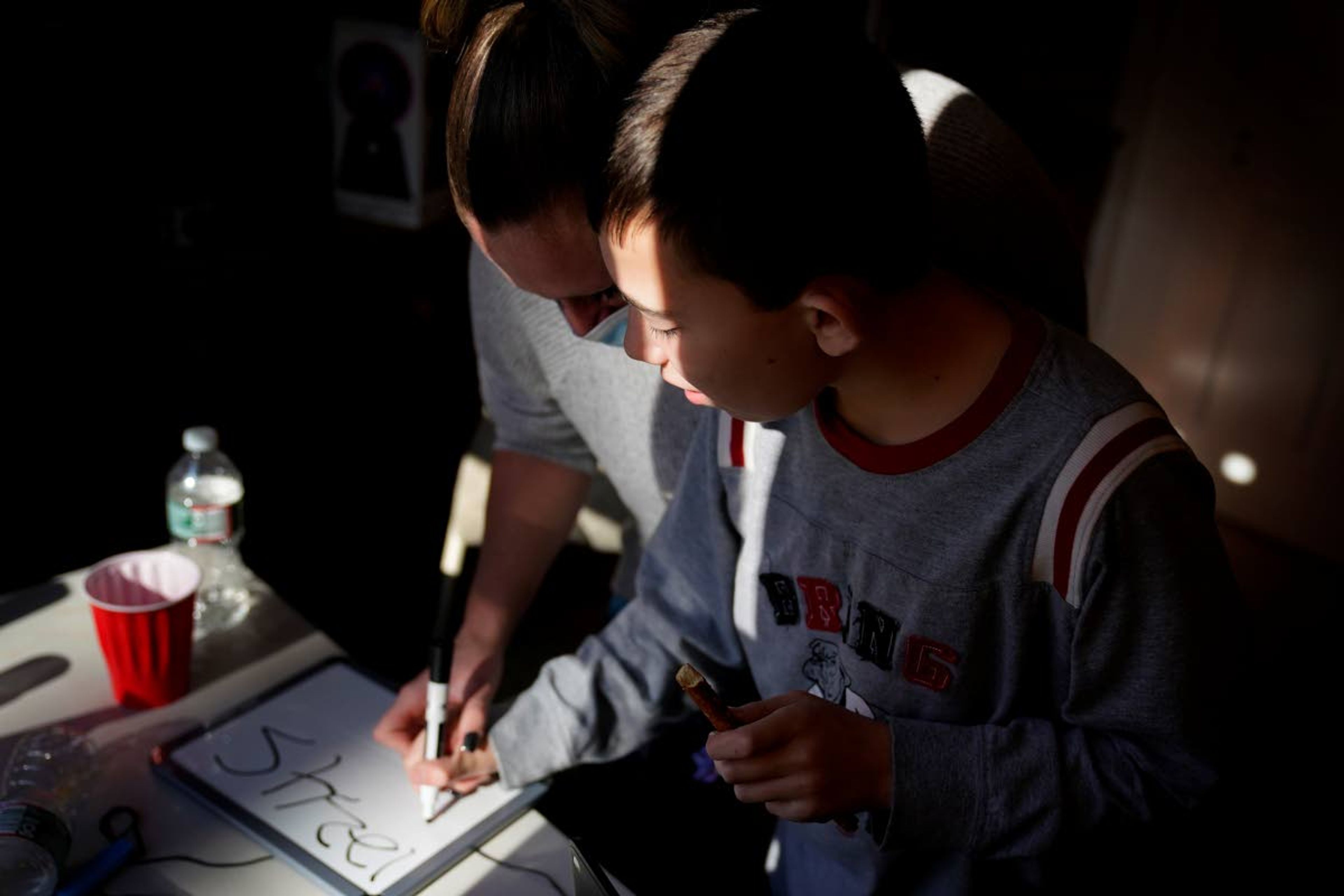

The teenager, who has autism and is nonverbal, often wanted no part of his online group speech therapy sessions, and when he did participate, he needed constant hands-on guidance from aides hired by his family. He briefly returned to his private Denville, N.J., school for two days a week, but surging coronavirus infections quickly pushed learning back online through at least Dec. 10.

Some of Josh’s progress “has been undone, and there are no plans to make it up,” said Sharon MacGregor, who has been involved in the boy’s care since she began dating his father several years ago.

The same frustrations are shared by many of the nation’s 7 million students with disabilities — a group representing 14 percent of American schoolchildren. Advocates for these students say the extended months of learning from home and erratic attempts to reopen schools are deepening a crisis that began with the switch to distance learning in March.

Some schools have prioritized high-needs students in reopening plans, bringing small numbers of them back to campuses that otherwise are sticking with distance learning. But those options have only fueled further anguish when they have been reversed because of the virus, and educators say personalized video sessions remain poor substitutes for classroom experience.

Alarmed by their children’s setbacks in skills and behaviors, parents are pursuing legal challenges and requesting makeup services. Many worry that the ground lost will be impossible to recover.

“Regression is something that will be very, very hard to recuperate from,” said Robin Lake, director of the Center on Reinventing Public Education.

In a move that seemed to acknowledge the importance of in-person learning, New York City announced Sunday that it will reopen the nation’s largest school system to in-person learning, including programs serving special-needs students at all grade levels. The announcement marked a major reversal after New York schools were shut down because of rising COVID-19 cases.

School districts have also struggled to deliver guaranteed services such as physical therapy that must be done in person or that require equipment, according to a recent report from the Government Accountability Office.

To his family’s relief, sixth-grader Griffin Stinner returned to school four days a week in mid-October when special education students were among the first to return to the Kenmore Town of Tonawanda Union Free School District in western New York state. But it did not last. Shortly before Thanksgiving, the district announced it would revert to fully remote learning because of the region’s rising virus caseload.

Griffin’s mother, Dawn, a teacher who is leading her preschool class of 4- and 5-year-olds remotely, called the situation “frustrating beyond belief.” After the initial shutdown in the spring, Griffin, who is nonverbal and has autism, would put on his shoes after breakfast to await the bus and cry over the loss of routine.

His mother would stand next to him and sign him in and out of lessons on a computer multiple times a day. “It was just really hard for him to grasp the concept that this was school,” she said.

Having to pivot again is “going to be a huge disruption in his life,” she said.

The federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act guarantees a free public education to children with disabilities and allows for “compensatory” services if a state education agency, in response to a complaint, determines that more needs to be done. Now parents are starting to make requests.

“It is becoming a major issue for our local directors,” said Phyllis Wolfram, executive director of the Council of Administrators of Special Education, or CASE.

To make up every hour lost — on top of providing services going forward — would be impossible. Educators will need to make individual decisions based on where a student is today, compared with their status before services stopped or changed, she said.

Speech pathologist Tara Kirkpatrick said the video sessions she conducts from her Comal, Texas, school office bear little resemblance to speech therapy delivered face to face. On video, she cannot tap a student’s desk to get them back on track.

Still, she believes teachers and families are doing their best under the circumstances.

“It’s not ideal ... and there’s nothing that we can do about that right now,” she said.

Not everyone agrees. A federal class-action lawsuit that named every state education department in the country sought a court order to either immediately reopen schools for students with special needs or issue vouchers for parents who have had to leave jobs or hire outside help to fill in the gaps.

A judge in New York City dismissed the suit, ruling that the court lacked jurisdiction, but not before more than 500 families in 35 states had moved to sign on.

“It’s a horror what’s going on,” said attorney Patrick Donohue, who filed the complaint and plans to appeal its dismissal. “We have kids who were walking, now aren’t walking. Kids who were talking, now aren’t talking. Kids who didn’t have any potty-training issues, now they’re not potty-trained.”

Older students aging out of services will not have time to recover, Donohue said. Federal law entitles students with disabilities educational services up to the age of 21.

Educators, Wolfram said, share parents’ concerns about students falling behind, but they are “at the mercy of the pandemic” and the rules adopted by governors and health departments.

Even fully reopening schools will not be enough, she said.

“It’s going to depend a lot on the resources that are available,” she said, citing potential help from local, state and federal governments. “And do we have the staff to do it? There are a lot of obstacles.”