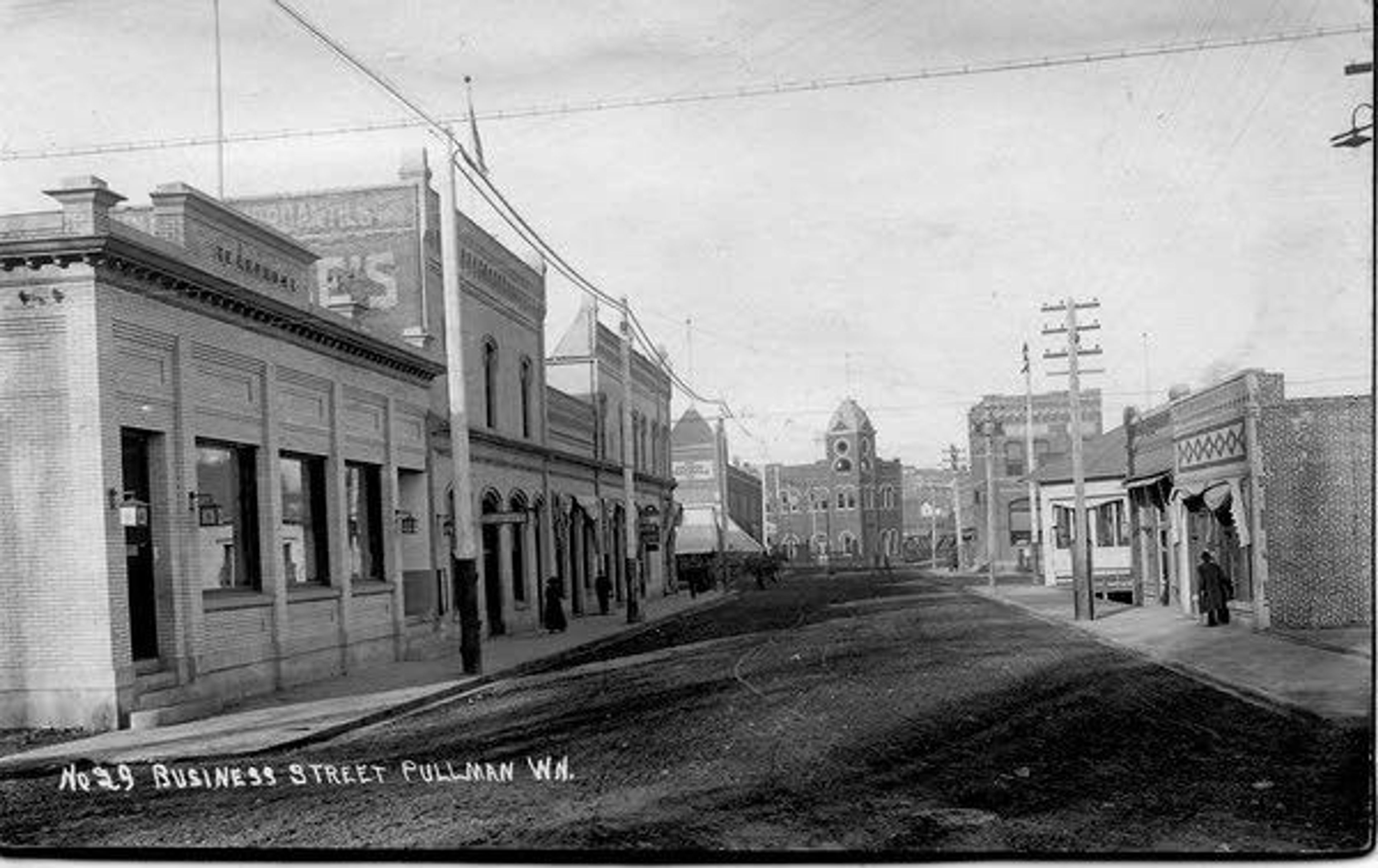

Nearby History: Early Pullman mail practices launched road improvements and town growth

The first official post office in Pullman opened in a mercantile store at 223 E. Main St., with store owner Orville Stewart serving as postmaster. Since postmasters were political appointments that changed with the election of each U.S. president, Stewart served five years (1881-1885). In 1888, he became Pullman's first mayor.

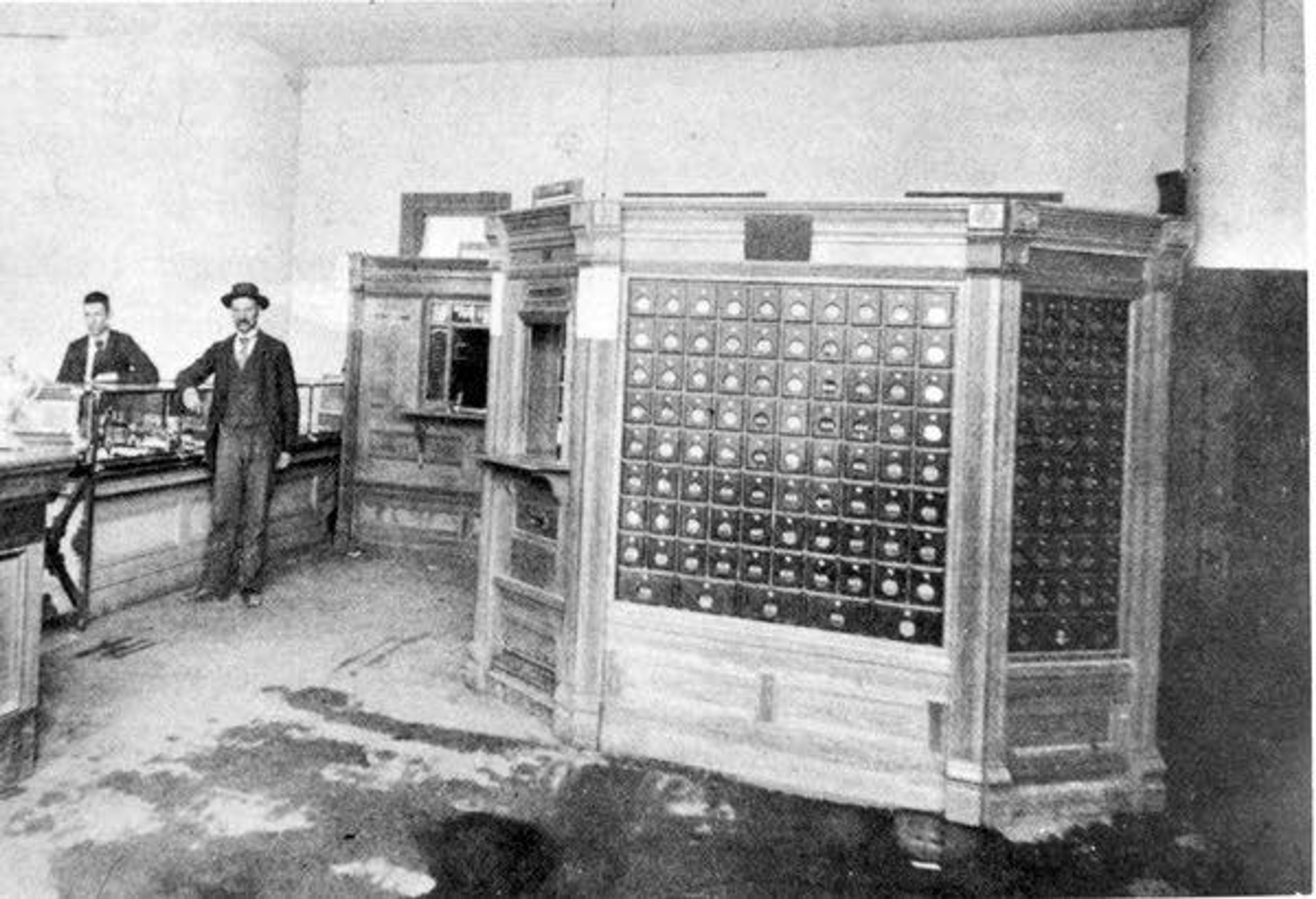

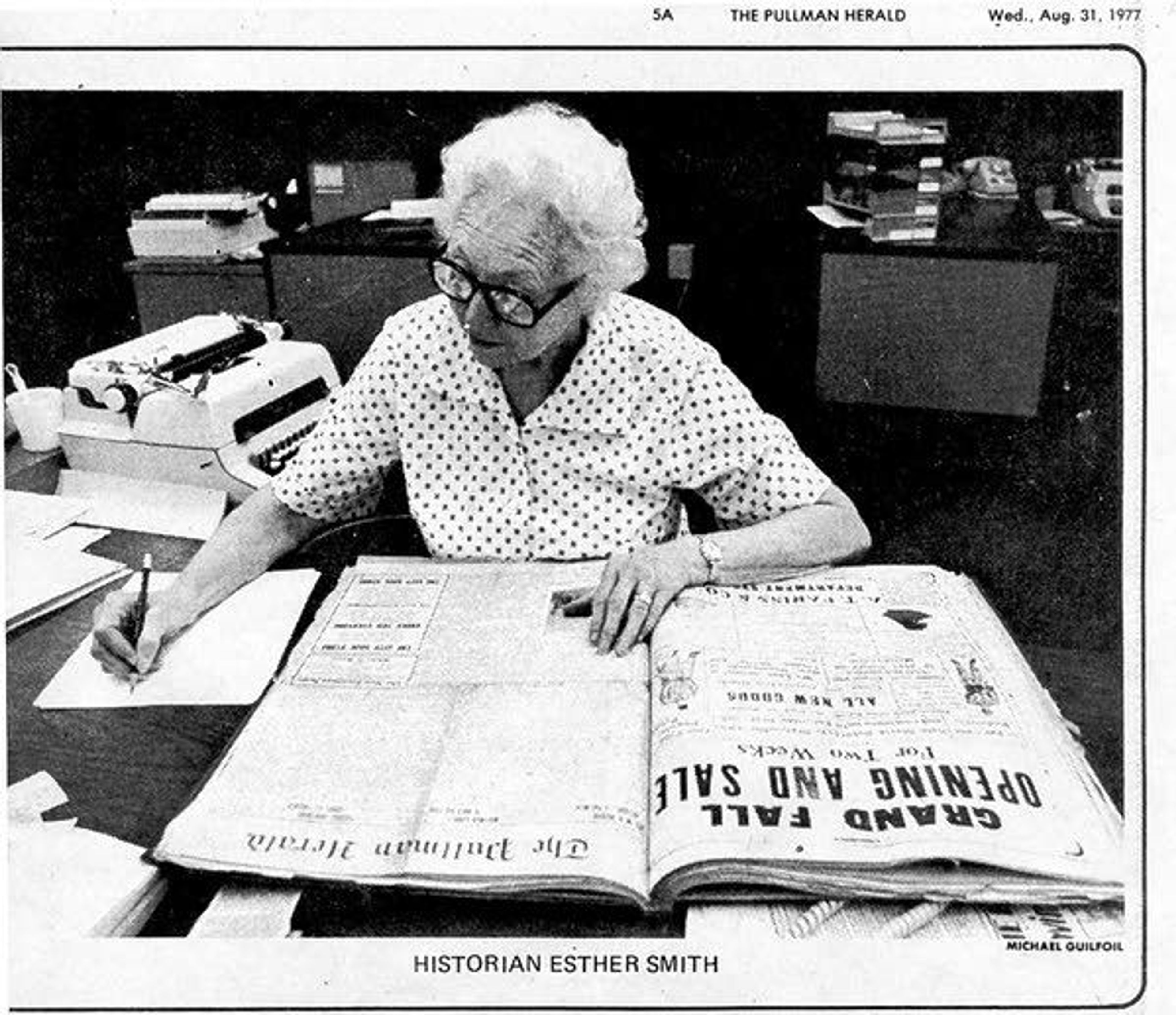

According to Bunchgrass Historian writer Esther Pond Smith (1899-1988), the second post office, with Eugene W. Downen as postmaster, was in Downen's dry goods and clothing business at 115 N. Grand Ave. Each postmaster in those early years was required to furnish room, equipment and delivery boxes. Thus, his place of business was a logical site.

In 1885 and 1887, mail began to arrive regularly on the OR & N and Northern Pacific railroad, replacing pony and wagon delivery. Smith wrote, "It was the job of the local postmaster to carry it to and from the depot, on foot, generally using a mail pouch."

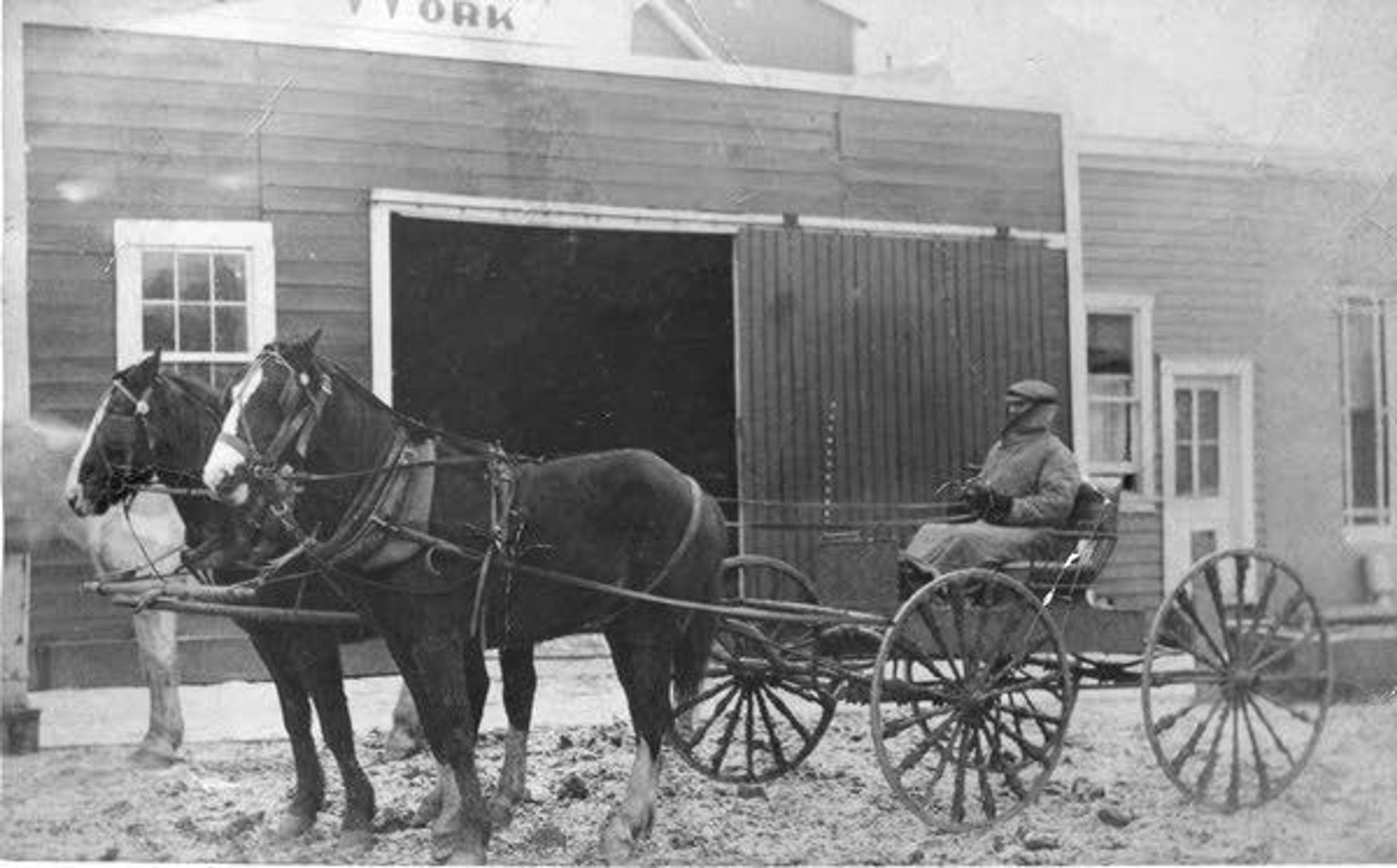

But as both the population and the amount of mail grew, a team of horses and buggy, and later a "hack," with drivers solicited from local residents, did the hauling.

John T. Lobaugh took over as Pullman's third postmaster in 1889. The post office moved again to Main Street but was destroyed by fire in 1890 along with much of the rest of downtown. With the forced relocation, Lobaugh added 51 lock boxes, Pullman rose from a fourth- to a third-class post office, and the socializing practice of visiting with friends while in line for mail at the general delivery desk started to give way.

Soon, "there were never enough" lock boxes, Smith said. In 1903, Pullman became a second-class post office, and the burden of paying for furnishings and equipment shifted from postmaster to the government. Pullman's sixth postmaster, King P. Allen, serving from 1902 to 1914, was the first to be paid for full-time work. Allen was also the first to oversee Pullman's "City Free Delivery" of mail directly to boxes at residences and businesses. Rural Free Delivery out of the Pullman post office began in 1902 to patrons who provided a mail box or pouch on a post at the entrance of their farms and who maintained passable roads year round. In many cases, horses were needed even on roads deemed "passable." The first three rural mail carriers, William H. Tapp, B.A. Davis and W.C. Campbell each had a route 20 to 30 miles long.

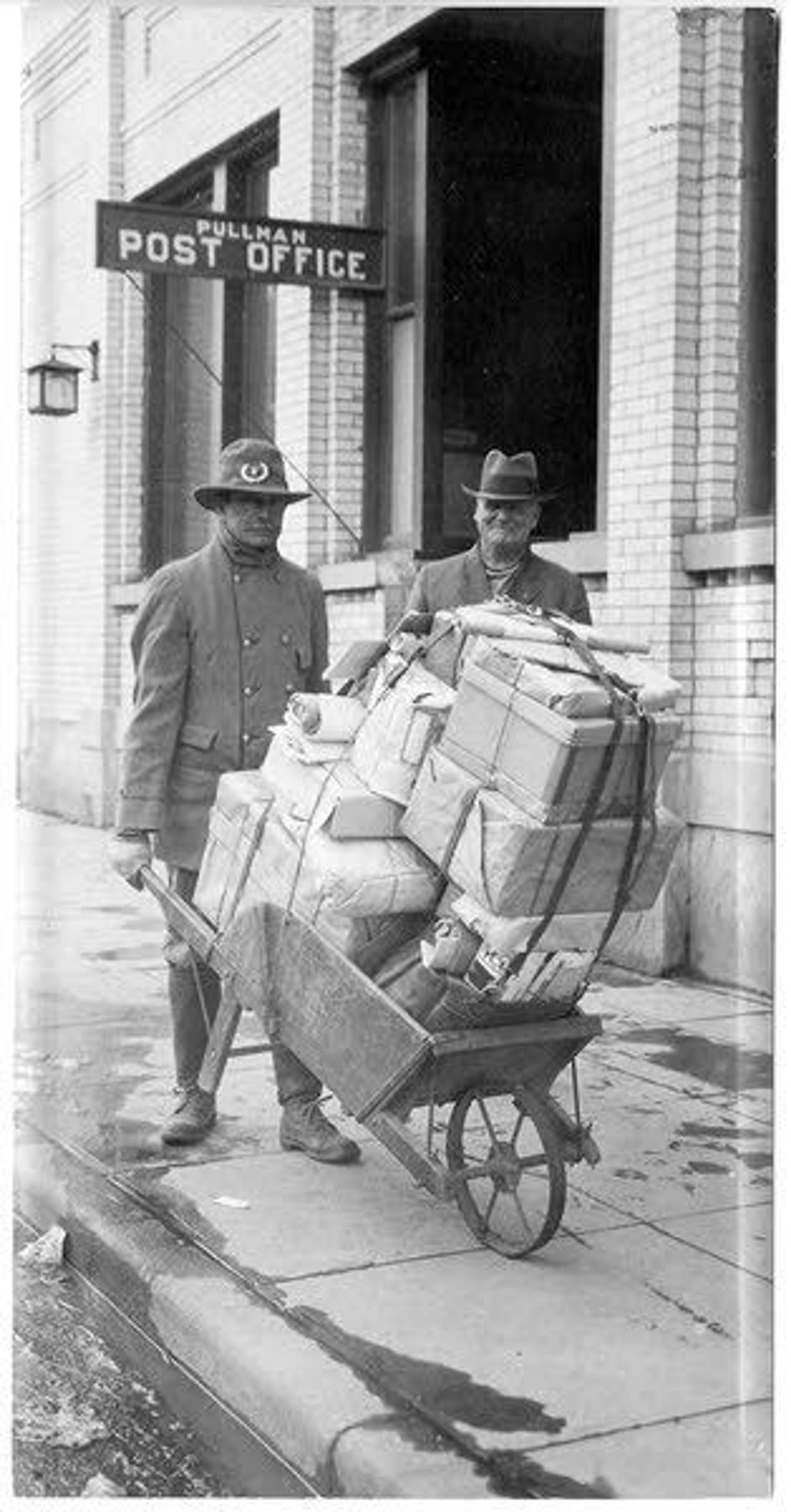

To prepare for City Free Delivery, streets were labeled and homes and businesses numbered. Patrons had to pay for their own delivery boxes. Applicants for mail carriers had to pass an examination. Pullman's first city carriers were W.H. Latta and Will Wallis. They "traveled about on foot with heavy pouches slung over their shoulders," Smith said, noting that Latta brought his load to College Hill in a wheelbarrow or sled and stored part of the load in a locked box on Maiden Lane while delivering the rest.

The delivery of packages, or Parcel Post, started with both rural and urban routes in 1913. Still, carriers furnished their own transportation - whether horses and buggies or automobiles and trucks - according to road conditions. Parcel Post wagons had to be painted light blue.

Parcel post deliveries enlarged families' shopping options and selection of everything from clothes to tools.

In Pullman, Washington State College students were by far the greatest patrons, Smith said: "Once a week nearly every student would pack his or her dirty clothes in a brown canvas-covered box, tighten the straps and address it to mother. For 15 cents each way, the box would be returned in a few days with clean clothes and a few cookies and goodies tucked in with them."

Ah yes. This early practice set a lasting precedent. I have older sisters, and I remember well the same scenario in the 1940s when they were away at school. They knew it would work, because "the mail must go through."

Joann C. Jones is curator emeritus of the Latah County Historical Society. Email her at joann.jones27@yahoo.com.