It certainly seems like pets will grieve the loss of another they have lived with, but is it really grief as we know it?

Grief in humans is defined by various sources as a natural response to loss, such as the death of a loved one, a serious illness or the end of a relationship. Grief is known to trigger a range of difficult emotions and even disrupt physical health, when it is hard to sleep, eat or concentrate.

For this writer, I find this to be accurate personally. Once I realized my parents had aged to the point that there would be no more hunts with Dad, or meals at the family table prepared by Mom, my grief started in earnest. By the time they passed, I had gotten it all out and the rest of the chores for caring for them and their estate came easily.

But do animals, including our domestic pets, “feel” similarly, say when a co-inhabitant of the house dies? How about cows in a pasture? Do they feel something for herd mates?

Frenchman Rene Descartes, philosopher, mathematician and scientist, along with Nicolas Malebranche, a French theologian and philosopher, believed that animals are essentially the equivalent of machines and that they are unable to think or feel.

That idea seems stark and uncaring itself. How can one observe a trained herding animal and believe for one minute that they can’t think? It may not be thought like you or I have, but at some level, herding competence like this supersedes mere behavior and has to have thought.

Or watch herd animals like feral horses that live on both public and private lands in the U.S. If for some reason a herd member suffers an injury affecting mobility but is otherwise not life-threatening, they will change their behavior to survive.

Without being trained, the injured horse, despite suffering great pain as known to veterinary medicine, will change its behavior to survive. They tend to wander within the larger elements of their herd, eat a little, drink a little but otherwise appear to be just one of the horses. That’s because animals faced with predators in their environment must not appear weak or injured lest they become food.

It is common for elephants to show some form of grief when an offspring or herd mate drops dead. Films clearly show the large land mammals hanging around the decedent. They sometimes seem to be trying to get the dead elephant to at least rise to sternal recumbency if not stand. And yes, over time they move on to survive themselves.

We have perhaps all witnessed domestic pets wander our houses’ familiar hallways or similar pathways in the barn or shop as if looking for a deceased — shall we say — acquaintance. Is that, however, grief?

Affective neuroscience as written and practiced by the late Professor Yaak Panksepp and others, in Washington State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine, “outlined seven primary process (i.e., genetically provided) emotional systems.”

These are, “seeking, rage, fear, sexual lust, maternal care, separation-distress panic/grief (henceforth, simply panic) and joyful play,” as noted in a 2011 paper he published in Psychology with Douglas Watt at Cambridge City Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

Yes, Panksepp was the scientist who discovered laughter in rats, and I heard it personally when he demonstrated it to numerous scientific journalists who covered the story.

This is not simple instinct, although these are within the genes of the animal, too. These are a basic form of emotion in animals and people, so yes, animals also grieve.

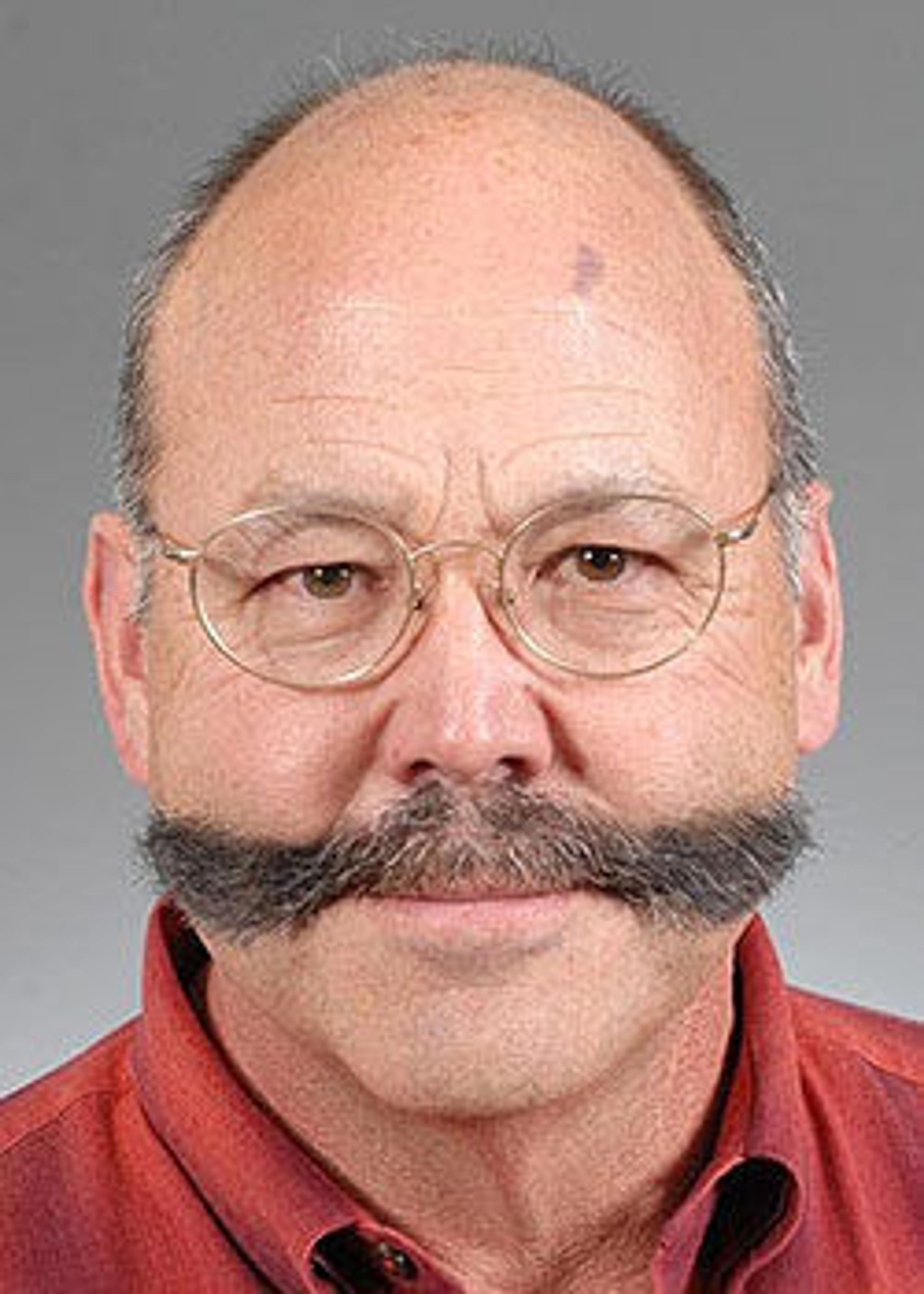

Powell, of Pullman, retired as public information officer for Washington State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine in Pullman. This column reflects his thoughts and no longer represents WSU. He may be contacted at charliepowell74@gmail.com.