There’s a wealth of informationin oral history

Earlier this year I joined the University of Idaho Library team as the new head of Special Collections and Archives. After working for many years at the Latah County Historical Society, it was a wonderful opportunity to expand my knowledge of Idaho history to include every corner of the Gem State.

The archival holdings cared for by the library are incredible and diverse. Researchers have free access to a wealth of information, from the personnel records of Bunker Hill Mining Company to case files for students that served in World War II, and from the congressional papers of Sen. McClure to the remarkable photography of Nellie Stockbridge. I could fill an entire edition of the Daily News listing the amazing items preserved inthe archives.

It’s impossible for me to pick a favorite from the many, many collections under our stewardship, but I will always have a special place in my heart for oral histories. Oral histories are unique among primary sources, which are generally defined as records created contemporaneously with the event being documented. An oral history interview, however, might be conducted years or decades after the period in question.

“The value of oral history lies largely in the way it helps to place people’s experiences within a larger social and historical context,” explains the Oral History Association. “Because it relies on memory, oral history captures recollections about the past filtered through the lens of a changing personal and social context.”

As a historian, I have long been interested in how our memories change over time and how they influence the construction of our identities.

Another reason oral histories are so valuable is that they provide a way to enrich more traditional records, like news reports, official government documents, or personal papers. For any number of reasons, a significant moment in time might not be represented in archives.

An oral history interview can go a long way in addressing an omission by documenting new information or adding additional perspectives. For example, relatively few written records were created by enslaved Africans and African Americans prior to theCivil War.

Their experiences were rarely told from a first-person perspective. Thankfully the Federal Writer’s Project’s Slave Narrative Collection was created during the Great Depression. The transcripts from those interviews are powerful and essential to our collective understanding of slavery and its terrible cost.

In the university’s Special Collections and Archives we preserve quite a few remarkable oral history projects. The largest of those is the Latah County Oral History Collection, which was conducted in the 1970s and 1980s by the local historical society. Several dozen folks who had been living in the county for decades were interviewed, providing hundreds of hours of recollections. Nearly the whole project has been digitized by the library and can be explored at lib.uidaho.edu/digital/lcoh/. Other examples of oral histories in our archives include the Rural Women’s History Project from the late 1980s, the Hispanic Oral History Project from 1991, and Palouse Anthropology’s oral history recordings conducted over the last decade. Most of the projects have not yet been digitized, but can be accessed by visiting us here at the library.

If reading this has reminded you that you really need to sit down with your granddad to capture his stories, I hope you will make plans to conduct your own oral history. With just a little planning, you too can be part of archiving history. Please contact our department for guidance on how to get started. We would be glad to offer advice on equipment, structuring questions, and other important considerations. If you would like to learn more about the oral history collections at the library, visit our website at.lib.uidaho.edu/special-collections/ and utilize the “Search Tools” in the left-hand menu.

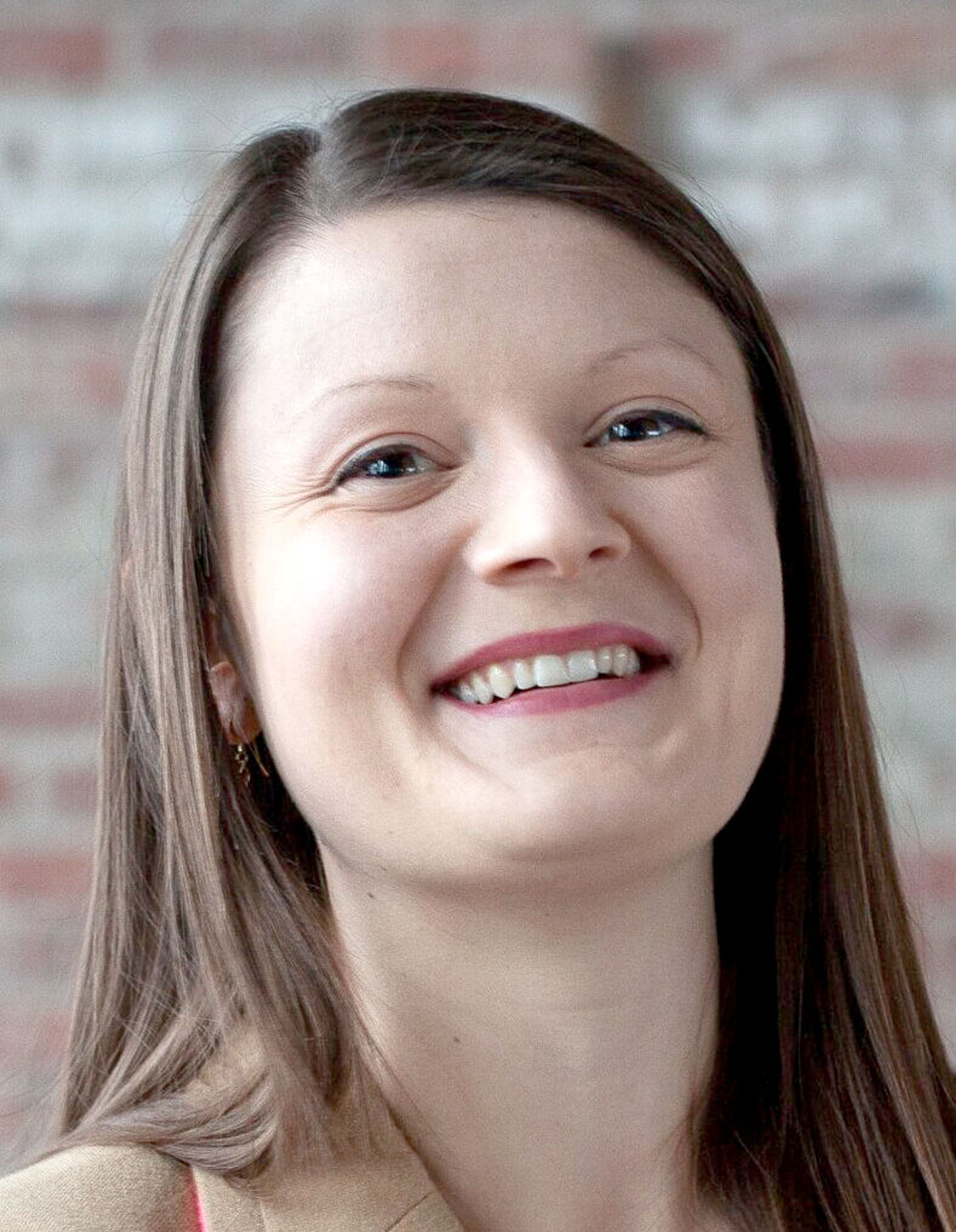

Dulce Kersting-Lark is the head of special collections and archives at the University of Idaho Library.