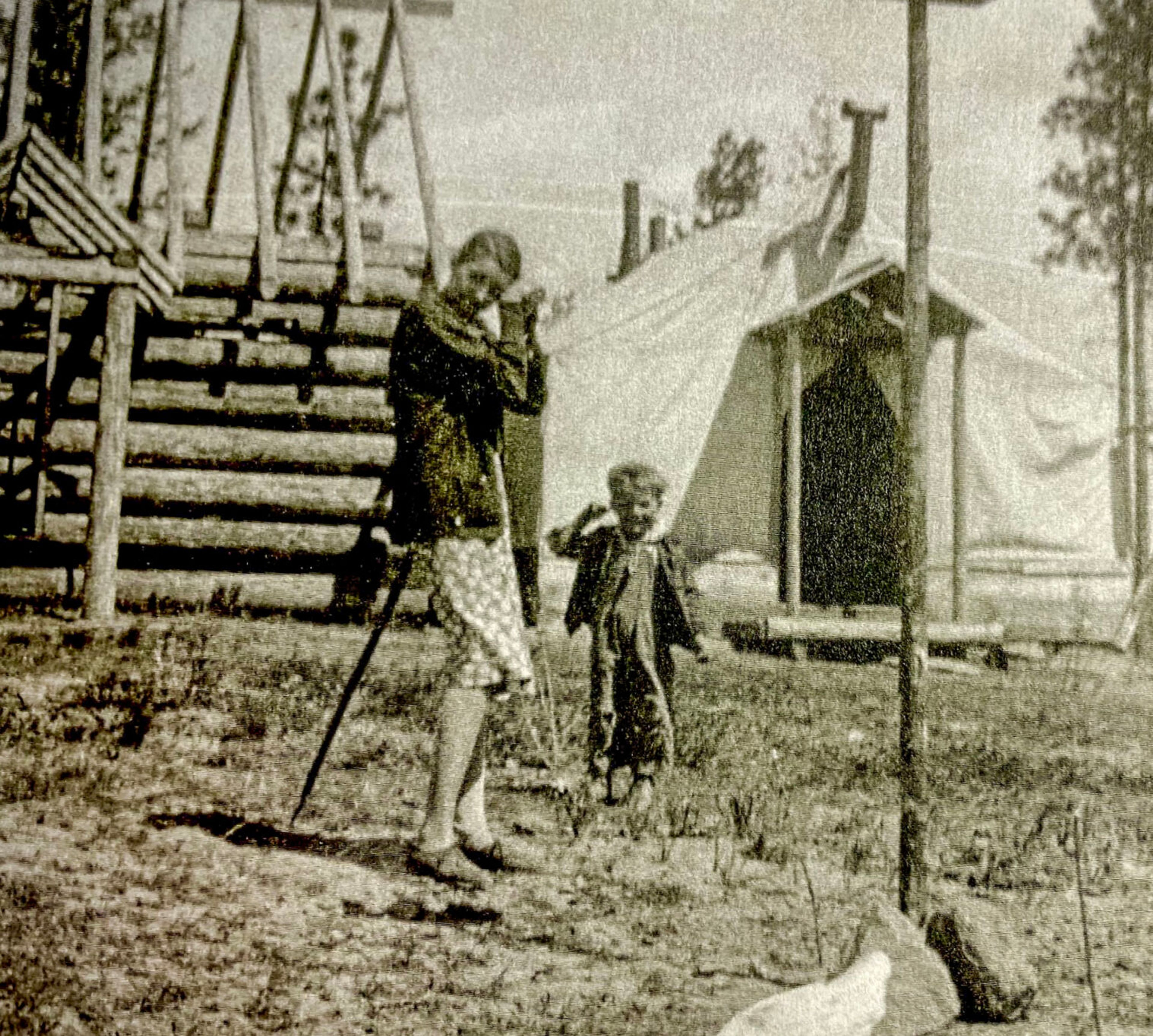

Along Hatter Creek near Princeton, a log cabin still stands

In the 1930s, a man built a home for his family along Hatter Creek near Princeton; years later, the family returns

“My grandfather had a farm. My dad had a garden. I’ve got a can opener.”

It’s an old joke.

However, besides my can opener, I have a smartphone (“smart” meaning it’s also a tiny computer), a big desktop computer and a laptop computer for when the other two aren’t appropriate for whatever reason. I didn’t buy a tablet, which is a bigger computer than a smartphone but smaller than a laptop. I showed restraint.

So I’m connected to the outside world through emails, texting, actual phone calls, Skype, Facebook and Googling on the internet. Just so I don’t get bored, I also have a high-definition television with cable service providing hundreds of channels and smaller TV sets in the bedroom and exercise room.

I get tired from all the problem-solving and maintenance these sensitive electronic marvels demand. The computer slows down when “cookies” and internet junk builds up, requiring cleansing (like cleaning one’s garage), or is actually “down” occasionally, unavailable for an hour or two. Or, it might be hacked or infected with a virus requiring more serious repair.

The computer mouse may die and need to be replaced, the cellphone coverage may disappear in some locations and its battery needs to be charged regularly. Sometimes the television cable menu is scrambled. All of this is frustrating, time-consuming and causes stress.

This self-pity dissolves instantly when I pause to read from my father’s diaries and his other writings.

“In 1928, I began paying for a 40-acre logged off tract on Hatter Creek, four miles south of Princeton. I took up my existence there during the Depression years of the 1930s. I fenced the place, dug a grade a quarter-mile long with pick and shovel from the Hatter Creek county road to my building site on the hill, cleared a few acres, and while living in a tent, started to build a log cabin.”

So without a bulldozer or other motorized equipment, my father dug a road up a hillside to the site of his new home and fenced it. Then he built a log cabin with only manual hand tools and with no formal carpentry training or experience. And I whined about maintaining my electronic equipment?

“In 1934, before I got the cabin finished, I married. Margaret Stater had a son, Stanley, by a previous marriage. We started our married life in a tent. I soon wished the cabin was finished, for now I had a family to support and had to work out to do it. There was little time to finish the building.”

My mother, who left a comfortable life living in Southern California to marry Dad, wrote about Christmastime during the Depression.

“We were living in a tent, on a stump farm. The tent had a floor and four feet of board sides but the rest was tent.

“We had a Model-A Ford but it was used only for emergencies. My husband walked four miles to town and brought back necessary items in a backpack. Since we lived on a stump ranch, we had fuel for cooking and heat. Many didn’t.

“My husband was one of the fortunate ones who had a seasonal job. This meant work through the summer and fall on the railroad but nothing in a long winter. We bought a very small toy truck for our little boy. My husband made a footstool from a section of log for me.

“We had a small Christmas tree but no decorations. I made a small hole in each end of an egg and blew out the contents. After they dried, I painted them with watercolors and painted designs on the shells. They made wonderful decorations. I made Christmas cards out of construction paper and pen and ink.

“My husband’s family lived on a small farm. They had a big garden and shared with us. We had lots of beans, potatoes and carrots.

“On Christmas Day, we walked four miles and pulled our little son on a sled to get to my husband’s family for Christmas dinner. No turkey. No goose. But biscuits and gravy, and lots of beans, potatoes, and carrots.

“We had friends and neighbors, no luxuries, but plenty of beans, potatoes and carrots. I still don’t care for carrots.”

Dad worked at area sawmills, the Potlatch Mercantile store and the Washington, Idaho & Montana Railroad, which carried logs from the woods to the Potlatch Forests Inc. mill at Potlatch and brought mail to Princeton and other towns along the railway. None paid well in those days.

But somehow, between his family life and working away from the Hatter Creek site, he managed to finish the new home and get out of the tent.

“We had a one-room log cabin. It had a fireplace. Upstairs (a loft) were our beds, under the roof where we could hear the patter of rain on the shakes in stormy weather. A trap door in the cabin floor opened into our cellar, an excavated area cool in summer and resistant to cold in the winter. There, we kept vegetables and fruit we had canned. The walls of our cabin were 14 inches thick.”

They had chickens, a pig, a cow and a garden. Stanley helped Dad saw wood for the kitchen range and the fireplace.

The chores were endless.

“I enjoyed every hour of it,” he wrote about the place he called Glenconifer. “I liked the solitude and the freedom. It may have been the brashness of youth, but I got pleasure from the hard work associated with living there. Cutting down trees, sawing wood, piling and burning the slash to clear the land for the plow was fun.”

But Dad soon realized he needed a full-time, year-round job to survive. He was surprised when opportunity came calling. The Princeton postmaster, George Guernsey, was retiring and asked Dad if he wanted the job. It only took Dad seconds to decide. Here was full-time work with the federal government that had benefits, including retirement pay.

In those days, politics was a factor in the selection of postmasters. John Lienhard, of Princeton, was the Democratic precinct committeeman and had the sole privilege and responsibility of selecting a new one. He endorsed my father, stipulating Dad also had to pass a civil service exam.

Feb. 1, 1940, Dad started a 30-year career as the Princeton Post Office postmaster.

My folks then made a painful decision — they had to leave their cherished cabin in the country. The four-mile dirt road to Princeton was impassable sometimes during winter snowstorms or when covered by high water in the spring flooding.

They found a rental house in Princeton before later buying one of their own.

Mom, a social animal, enjoyed living in the town of 84 people. She made many friends and became an active member of the little church.

On Easter 1940, the family returned to the farm for a visit.

“Easter Sunday was a nice day, sunny and warm. In Princeton the ground was soggy and wet, but on our hill all was firm and fine. The flowers were blooming. It looked good to us.

“Stanley (7 years old), wanted to stay up there for the rest of the week. He stoutly maintained he would be willing to stay alone in the cabin. To get this desire accomplished, he went off ‘hunting’ over the hill, hoping we would get tired of waiting for him to come back and return to Princeton without him.”

Dad also was missing the Hatter Creek farm.

“1941: I am an old grouch. At our Hatter Creek home, I had the whole farm to myself for weeks at a time without a single visitor. Here in town, the visitors to our rough dwelling are many. Margaret likes it. She is caught up in the whirl of activities that bring many church people to our house. I have a hard time adapting to this.

“I get away from the life in town when I get up at 3 a.m. and go up to Glenconifer to make wood. It is just wonderful to be at work there when the new day comes into being. This is spring and summer when the days are long and I am full of ambition and vigor.

“But I must say that I’ve got to be philosophic about my urge to be alone and get used to being around people. My post office job is going to throw me into contact with many, and I might as well get used to it.”

My parents couldn’t afford to pay for their new home and the farm on Hatter Creek. They would have to sell the farm.

It was a hard decision, especially for my father. He loved the sights and smell of the woods and to stand by the cabin and look south over the hills to Moscow Mountain; to watch the sun rise in the east over the Hoodoo Mountains and set in the west over the farmlands of the Palouse country.

Selling Glenconifer was a bitter experience.

The land passed through several owners over the years and, in 1978, it was purchased by David Johnson, a reporter for the Lewiston Tribune. I also was a reporter for the Tribune and informed Johnson of its history. He immediately wanted to contact my father, then retired and living in Lewiston, and invite him up for a visit.

I said I would tell Dad.

“No,” said my father. “I’m not going back there. And I don’t want to talk to him about my time there.”

I asked why not.

“It would only make me sad and depressed,” he said. “I’m not doing that.”

I knew he meant it.

I discovered later that Dad wrote Johnson several letters describing his life on Hatter Creek.

I knew that was as much that would be forthcoming.

Dad died in 2001. We scattered his ashes at his old elk hunting camp at the Incline, high in the mountains past Clarkia.

I wondered later if his first choice would have been at his beloved Glenconifer.

In October 2003, my wife, Robyn Peterson, and I took my mom to see the Hatter Creek farm. She was overjoyed to see the old cabin still standing and inhabited by Johnson’s daughter, Greta Lovell, and her husband, Bruce Lovell. Greta’s parents lived in a new log house nearby.

A new addition was being built to the original cabin which Mom thought was just wonderful.

“I can’t believe the old cabin is still standing,” she said several times. “It brings back so many wonderful memories.”

We had driven up the road my dad dug with a shovel and pick so long ago in 1928 to where he then built this log cabin that was still standing and still inhabited, in this place he loved and hated to leave.

I felt proud for what he had accomplished and sad he felt he had to leave.

Johnson wrote a column for the Tribune circa 1988 about winter giving way to spring on Dad’s beloved land. It begins:

“HATTER CREEK — Out in the forest these days, winter and spring are waging a duel. It is a traditional struggle; one that reminds me of our link to the land.”

Then it concludes: “The snow around the old homestead cabin is all but gone. The cabin’s builder, who writes to us now and then and shares his adventures from the past, picked the right spot for a home. His house, built 51 years ago, is a stout structure. Its log walls and cedar shake roof have withstood the test of time. It is one of our prized possessions, but it’s still really his.”

Bull is a former sports reporter for the Lewiston Tribune as well as a longtime freelance contributor who now lives in Oregon. He may be contacted at andybull253@gmail.com.