Anti-hazing advocates hopeful for Sam’s Law

Senate may vote on bill as soon as today after near-unanimous House approval

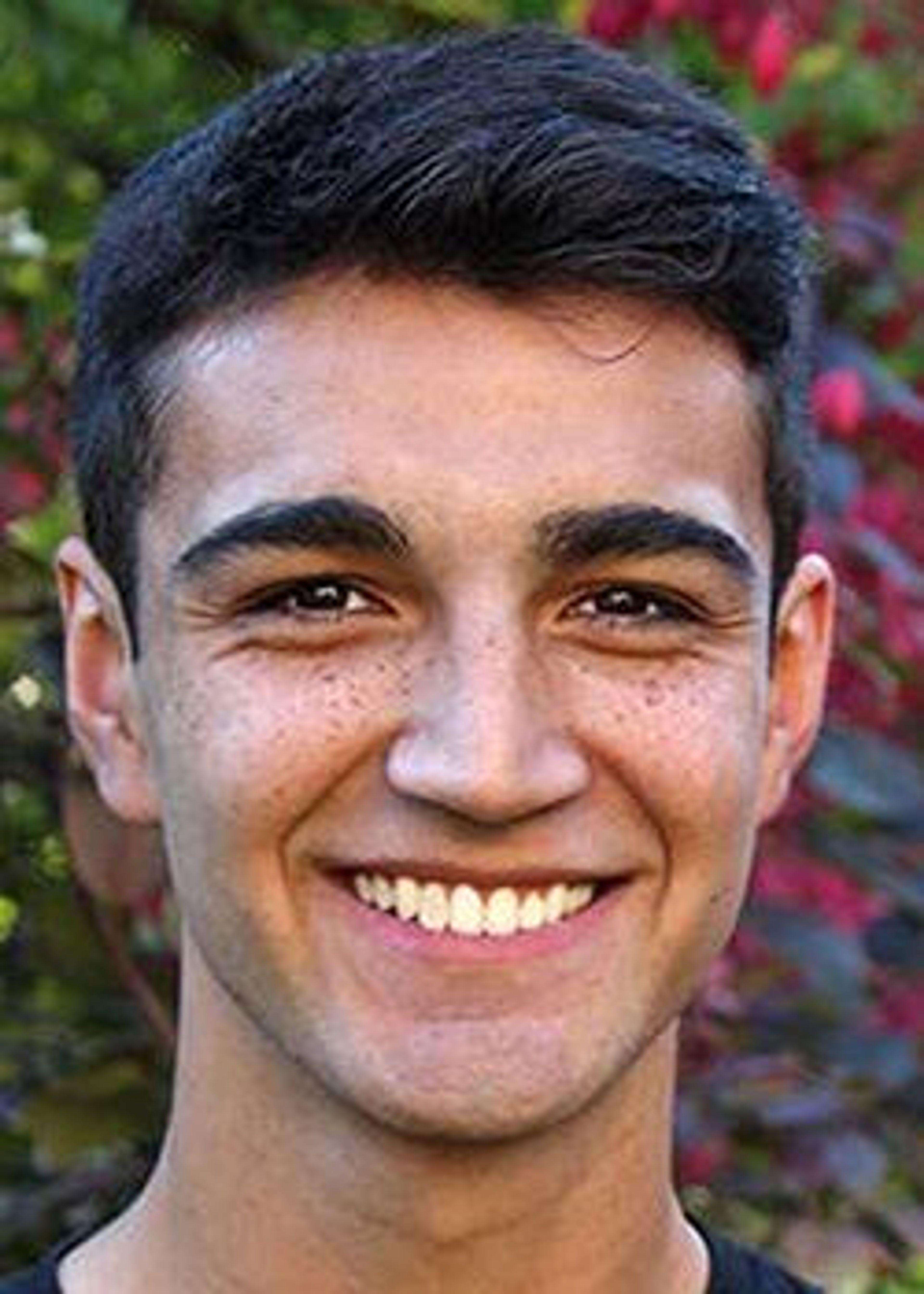

As Washington state legislators approach the March 10 end of the session, the parents of Sam Martinez, a Washington State University freshman and Alpha Tau Omega pledge, are hoping the legislation named after their son will help prevent future hazing-related deaths.

Martinez died of alcohol poisoning in 2019 after he and another freshman were told to finish roughly half a gallon of rum.

Jolayn Houtz, Sam’s mother, said if the family had known about the fraternity’s history of hazing, Sam would still be alive today.

“(Sam) would not have wanted to join, and we certainly would not have let him join a fraternity that had a long history of hazing and drug and alcohol violations,” she said. “We did not know. WSU knew, and the national fraternity knew, but that information was hidden from the public.”

Hector Martinez, Sam’s father, said at a testimony in the Senate Ways and Means Committee on Saturday how he fondly remembered community service trips to Mexico with Sam, and that he believes his son would want him to continue helping other young people and families.

“Losing Sam hasn’t only affected and changed my wife, my daughter and myself,” he told the committee. “It has had a terrible ripple effect across Sam’s wide circle of friends and family. We are still relearning how to live without our son. No other family should ever have to face the unthinkable pain of losing their child.”

HB 1751 or “Sam’s Law Act,” (previously the Hazing Prevention and Reduction Act) would expand the definition of hazing by requiring public and private institutions of higher education to publicly publish findings of hazing for not only sororities and fraternities, but athletic teams, living groups and other clubs — and maintain a record for the past five years.

That requirement is an amendment from an earlier version of the bill, which sought to require a notification for any hazing investigation to be published online. The bill’s sponsor, Rep. Mari Leavitt, D-University Place, said although she understands why the family initially wanted that information public, the change is meant to make investigations run smoothly.

“It’s kind of similar to Title IX investigations. You don’t post that you started one on a public website, because when you do investigations like hazing, or any kind of student conduct issues, folks clam up, and they go quiet,” Leavitt said. “Or they may not feel obligated to show up to a meeting that they’ve been requested to attend. It really can have a chilling effect on our ability to actually have findings to hold people accountable, and to prevent future incidents.”

Under the bill, fraternities and sororities would also be required to notify public or private institutions of higher education about their own investigations of hazing at local chapters, along with the full report and findings when they’re completed. They would also have to notify those institutions before chartering, rechartering, opening or reopening a local chapter.

It would further require institutions of higher education to provide educational training on hazing to students and employees beginning in the fall of 2022, and require employees to report hazing violations.

Houtz told the Ways and Means Committee on Saturday she believes things might have been different if one of the students who witnessed Sam’s hazing had been educated on hazing.

“What if just one of those young men had been trained to recognize hazing, and had intervened or called for help?” she said.

It would also require the public and private universities and colleges to explicitly prohibit hazing on and off campus, and establish a hazing prevention committee at public institutions of higher education.

State Senators may vote on the bill as early as this morning, Houtz said. The legislation is expected to pass, having moved through the House with nearly unanimous bipartisan approval.

The legislation is “groundbreaking” in its update to the definition of hazing and requirements for universities and colleges, Houtz said.

“We haven’t done anything with our hazing law in Washington state since it was placed on the books in 1993,” she said. “That’s almost 30 years when we haven’t looked at it and the world has changed so much. And we know this is still going on — we know hazing is still a problem.”

A companion bill, HB 1758, did not make it out of the House in time to pass this session, but it planned to be reintroduced next year, Leavitt said. HB 1758 aimed to change hazing from a misdemeanor to a gross misdemeanor, and a class C felony in the case where it causes substantial bodily harm.

In Sam’s case, the one-year statute of limitations for misdemeanors in Washington means by the time the investigation was completed for his death, those being investigated could not be prosecuted for hazing.

Instead, 15 people involved in the hazing were charged with furnishing liquor to minors, and sentenced to between one and 19 days in jail and a $500 fine. Others are continuing their cases into April of this year.

“Having substantial bodily harm or death be considered a Class C felony really opens up (police detectives’) ability to gather information,” Leavitt said. “It doesn’t mean they’ll necessarily get charged that way, but it allows them to seek information that they just can’t get ... (when) confined with the timeframes that they have as a misdemeanor. That’s why it’s super important that we’ll come back next year and do that.”

Sun may be contacted at rsun@lmtribune.com or on Twitter at @Rachel_M_Sun. This report is made possible by the Lewis-Clark Valley Healthcare Foundation in partnership with Northwest Public Broadcasting, the Lewiston Tribune and the Moscow-Pullman Daily News.