Biden leads but Trump within striking distance

WAYZATA, Minn. — For such a volatile year, the White House race between President Donald Trump and Democratic challenger Joe Biden has been remarkably consistent.

With Election Day just eight weeks away, Biden is maintaining the same comfortable lead in most national polls that he enjoyed through the summer. He also has an advantage, though narrower, in many of the battleground states that will decide the election. Trump remains in striking distance, banking on the intensity of his most loyal supporters and the hope that disillusioned Republicans ultimately swing his way.

Still, both parties are braced for the prospect of sudden changes ahead, particularly as Trump makes an aggressive pitch to white suburban voters focused on safety and fear of violent unrest. It’s unclear how well his rhetoric will resonate, but Democrats insist it can’t be ignored, especially in the upper Midwest.

That’s especially true in Minnesota, a state that hasn’t voted for a Republican presidential candidate since 1972. Democrats there say they’re increasingly concerned that the state is genuinely in play this year.

“Trump can win Minnesota,” said Rep. Dean Phillips, who in 2018 became the first Democrat to win his suburban Minneapolis district since 1960. “It’s real. It’s absolutely real.”

While Trump’s campaign is touting a play for Minnesota as a way to expand the electoral map, the president is playing defense in a host of the other battleground states he needs in order to secure the 270 Electoral College votes to keep the White House. Biden’s campaign is laser-focused on the states in the Midwest and close by that Trump flipped in 2016 — Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania — and also making a robust play for Arizona, a state that hasn’t backed a Democratic presidential candidate since 1996.

Biden is also redoubling his focus on Florida, the biggest prize among the perennial battlegrounds and a state that would virtually block Trump’s reelection if it swings Democratic. Biden’s allies hoped the devastating toll of the pandemic would put them in a strong position there, but a poll released on Tuesday found voters were closely divided. Sen. Kamala Harris, Biden’s running mate, will make the campaign’s first in-person appearance in Florida on Thursday.

Beyond Florida, recent polls suggest close races in Pennsylvania and North Carolina, while a Fox News poll conducted after the recent national conventions gave Biden an advantage in Wisconsin. Polls conducted earlier in the summer also suggested a Biden lead in Michigan. Another post-convention Fox News poll found a Biden advantage in Arizona.

Still, polls that showed competitive races or even Democratic advantages in traditionally Republican states proved to be false indicators for Democrats in 2016.

Biden’s aides are bullish about competing on a broad map that includes multiple states Trump won in 2016, including Florida, Arizona, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin.

“There’s a number of combinations that will allow us to get where we need to go and get over the 270 hump,” Jennifer O’Malley Dillon, Biden’s campaign manager, told reporters last week.

But Trump has some important organizational advantages.

The campaigns will match each other almost dollar for dollar on television advertising nationwide through Election Day — each side has reserved $149 million in TV ads — but the money isn’t distributed evenly, according to the ad tracking firm Kantar/CMAG. In Minnesota, for example, Trump is scheduled to spend four times as much as Biden.

Trump has been far more willing to invest his time with swing-state voters on the campaign trail. His rally last month in Mankato was his fifth appearance in Minnesota since taking office. He was in both Florida and North Carolina on Tuesday.

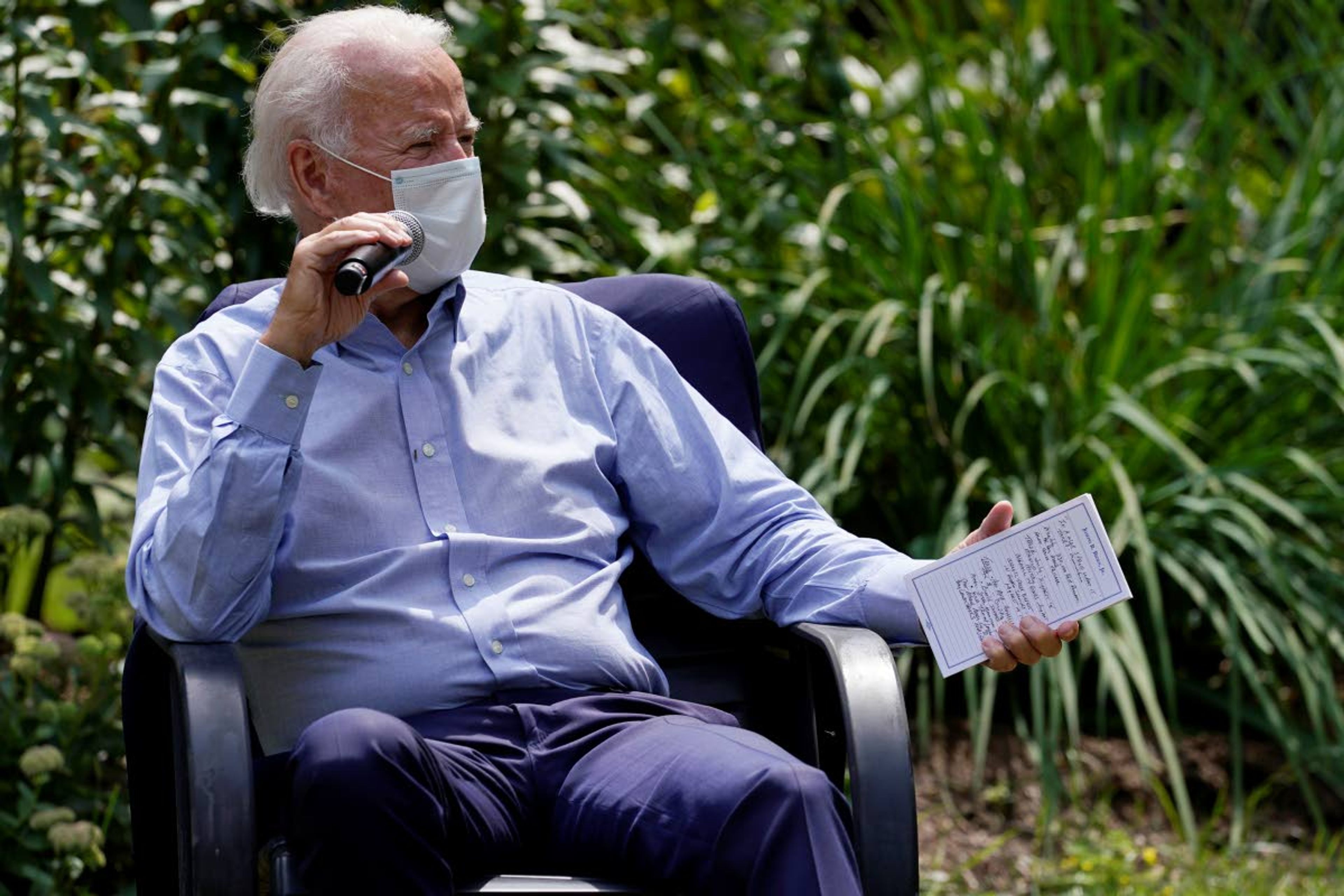

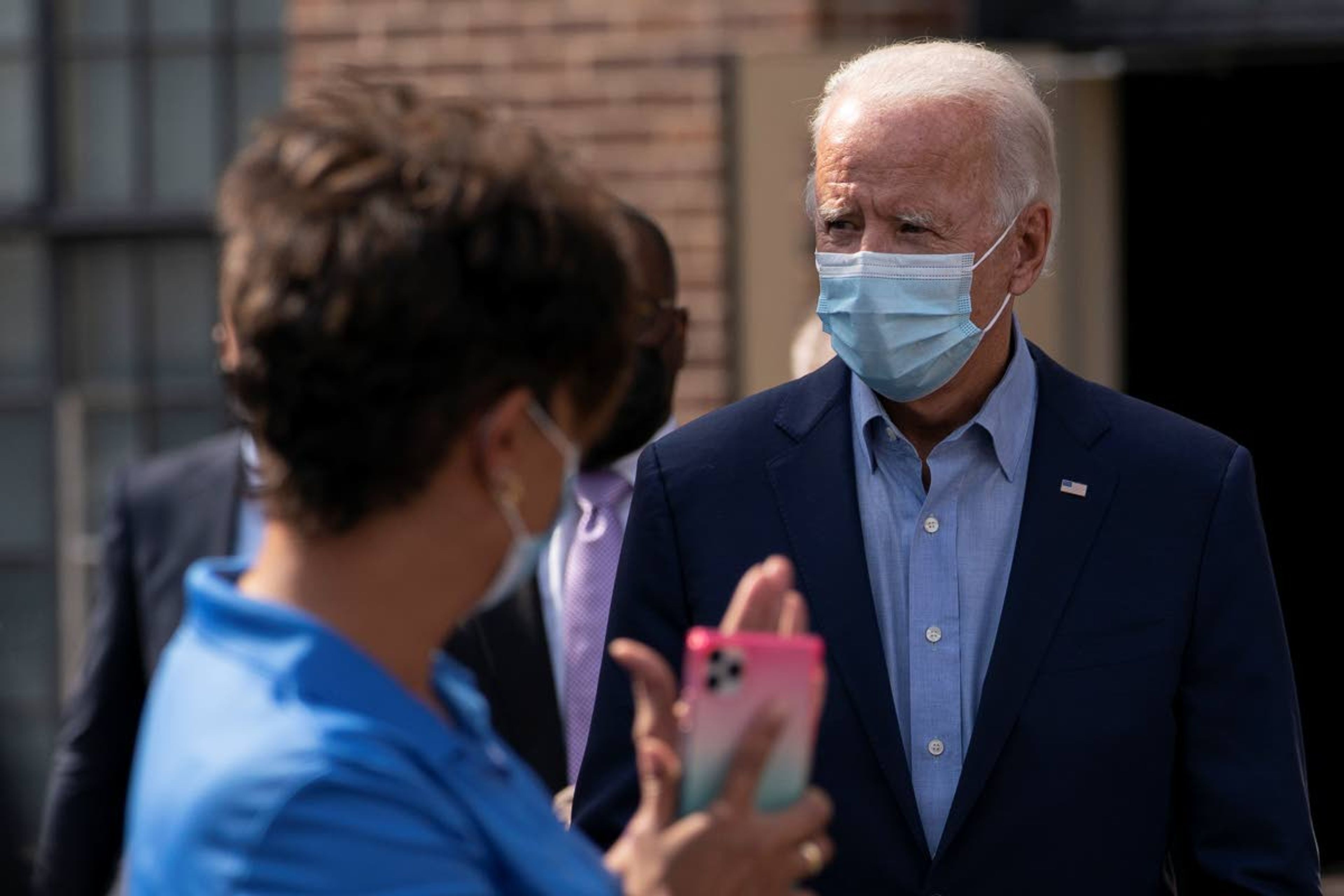

And while Biden resumed in-person campaigning last week after months of avoiding significant travel because of the pandemic, Trump is expected to embrace a much more aggressive campaign schedule than Biden in the coming weeks.

Republicans claim another practical advantage on the ground: People. Trump’s team has thousands of paid staff and volunteers across the country courting voters face-to-face, while Democrats are still conducting their canvassing efforts almost exclusively by phone and online.

White House chief of staff Mark Meadows claims increased momentum. Last week aboard Air Force One, as Trump was returning to Washington from a rally in Pennsylvania that drew thousands despite public health concerns, Meadows said: “It just continues to build bigger and bigger each time we go, Minnesota or Wisconsin or Pennsylvania or North Carolina. It just — the crowds keep getting bigger and bigger.”

Trump’s advisers say they are no longer writing off Michigan — and their $13.8 million in advertising reserves in the state, not far behind Biden’s $16.3 million, reflect their commitment. Trump aides are also optimistic about Pennsylvania, Florida, Wisconsin and Minnesota.

The race could ultimately come down to swing state suburbs, where many educated voters who have traditionally voted Republican have turned away from Trump’s GOP. The shift has fueled gains for Democrats in state elections since he took office, yet Trump’s team is betting that the focus on protest-related violence will scare some voters into giving him a second chance.

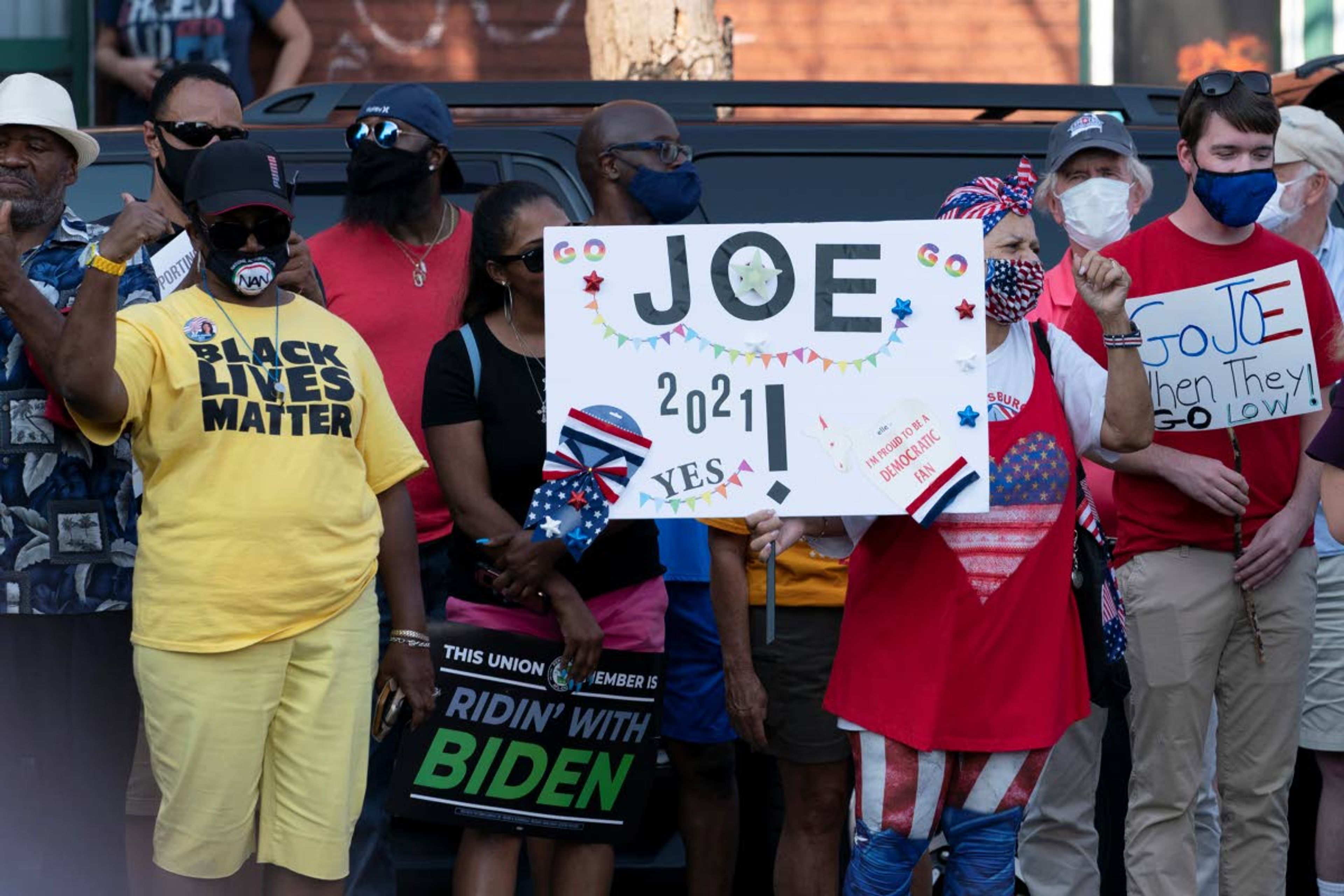

The balance for Democrats between embracing the Black Lives Matter movement and criticizing violence aimed at police is particularly sensitive in Wisconsin. The state has emerged as a center of the nation’s civil unrest following the recent police shooting of Jacob Blake, a Black man, in Kenosha and subsequent protests that sometimes became destructive.

Trump was a regular presence in Wisconsin even before the unrest, while Biden made his first stop of the campaign just last week.

Trump and his allies have also been a more visible presence in Pennsylvania, although Biden is catching up. The Democrat hosted a campaign event in the state on Monday, and both candidates plan to appear in Shanksville on Friday to mark the anniversary of the Sept. 11 attacks.

Terri Mitko, the Democratic Party chairwoman in Beaver County, one of the Democratic-leaning counties in western Pennsylvania where Trump pounded Hillary Clinton in 2016, predicted that most Trump voters would not abandon the president. She expects some independents and many new voters, however, to support Biden.

Still, she would like to see Biden emerge as a more visible presence.

“In Beaver County, we certainly would like to see him down here,” Mitko said. “People are asking for that.”

On Tuesday, Trump visited Winston-Salem, North Carolina, a top battleground state that became the nation’s first to send absentee ballots to voters late last week.

Biden’s campaign boasts that it’s already made 4 million calls to North Carolina voters, while Trump’s Tuesday appearance is one of a half-dozen he or the vice president has made in recent weeks.

The calculus for many voters is complicated as the nation struggles under the weight of the pandemic, the related economic fallout and sustained civil unrest.

Minnesota, which Trump lost by just 45,000 votes four years ago, offers a window into the nuanced debate.

During a recent afternoon in Wayzata, Simone Metzdorff, a 52-year-old operations manager at an insurance company, conceded that she doesn’t know which candidate she’ll support.

She cast her ballot for Trump in 2016, largely because she considered him “the lesser of two evils.” But she continues to think he’s “vulgar,” “too outspoken” and “not appealing.”

She says the protests are unlikely to decide her vote. She’s “appalled” by what happened to Floyd but also “110 percent supportive of the police.”

Her husband’s view of the Democrats is not ambivalent. John Metzdorff, a retired service technician, former Marine and Republican, said the day after Biden visited Kenosha: “Democrats, all of the sudden they change their tune. People are tired of rioting, and all of the sudden now Joe Biden is out?”

___

Peoples reported from New York. Associated Press writers Alexandra Jaffe and Zeke Miller in Washington; Thomas Beaumont in Des Moines, Iowa; Scott Bauer in Madison, Wisconsin; Jonathan Drew in Raleigh, North Carolina; and David Eggert in Lansing, Michigan, contributed.