Helping firefighters battle fatigue

UI researchers study contributing factors to fatalities among firefighters

Two researchers from the University of Idaho have found fatigue may be a major factor in accidents and deaths among firefighters.

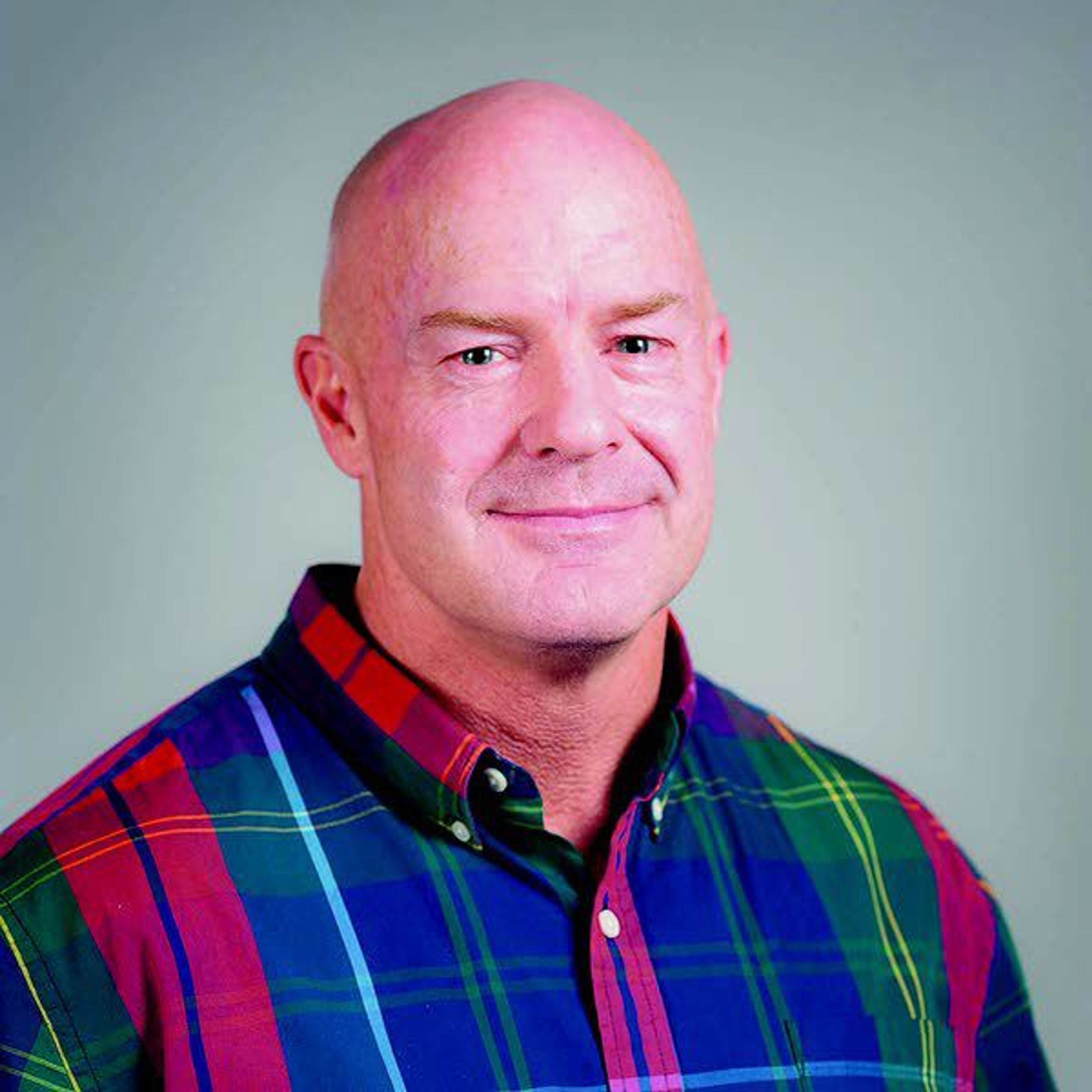

Randy Brooks, a professor with the UI's College of Natural Resources, said he was motivated to begin researching contributing factors to accidents among firefighters back in 2015 after one of his sons served on a crew with three firefighters who died combatting a blaze in Twisp, Wash.

"He actually texted me at 7:15 that night and said, 'we're moving to Twisp,' and I texted him back and said, 'dang, you guys are getting in there late, you're going to be tired,' " Brooks said. "At 5:30 the next morning, he texted me and said, 'we're headed out into a box canyon.' "

After that fatal fire, Brooks said he started talking to Callie Collins, who had just received her bachelor's degree in exercise science, about ways to address and study the underlying factors causing firefighter fatalities. Brooks said the study initially started out as a survey which became part of Collins' master's work.

"We decided to roll out and do a survey to ask firefighters what they thought was contributing to accidents, not just fatalities," Brooks said. "We sent the survey out and got 428 responses and found that fatigue was the No. 1 self-reported answer."

It had already been established, Brooks said, that leading causes of death among firefighters are cardiac arrest and vehicular accidents. He said he and Collins decided it may be beneficial to track the daily activity and body composition of firefighters to see how these may contribute to accidents.

Brooks said their initial group included nine smoke jumpers - an elite class of firefighters who drop in on parachutes to combat blazes in remote locations. That group has since doubled to 18, Brooks said.

Brooks said participants were outfitted with Fatigue Science Ready Bands - wearable devices that resemble fitbits, but rather than measuring heart rate and blood pressure, it uses accelerometers to measure motion behavior. Brooks said the devices calibrate to the individual's behavior after being worn for close to a week. Once it has been calibrated, he said, the band can show researchers trends in activity and rest that each user engages in over a period of time - anywhere from minute-to-minute updates to patterns that stretch back over months.

"It just tracks motion 24/7 and gives us movement data at one-minute intervals," Collins said. "What that is able to tell us is quantity and quality of sleep they're getting through movement."

Brooks said the devices were developed by the United States military to measure behavior in soldiers. The researchers behind the devices also developed an "alertness score" to gauge a subject's mental state. The trends and scores of each individual can then be pulled up on a phone app or tablet, Brooks said.

"This alertness score is actually a level of fatigue," Brooks said. "It's a scale of zero to 100, and I can tell anything above 90, your alertness is good."

Brooks said as scores become lower, impairment tends to become more and more evident.

Brooks pulled up a random firefighter whose score had dipped. According to the data, this person had spent just 5 percent of the previous three days with a score above 90.

"He probably just got back from a fire," Brooks said. "His reaction time is slowed by 55 percent and it's the equivalent of a blood alcohol concentration of greater than .08."

There are a number of additional variables being considered by the duo, including nutrition, body composition and stress.

Moving forward, Brooks and Collins, now working on a doctorate, hope to expand the scope of their study to include hotshots and engine crews as well. He said they will also ideally be able to look at more factors, including tracking cortisol levels - the stress hormone - in firefighters' hair samples. He said the research completed, while telling, is only beginning to illustrate the grand scope of the problem.

It will take a major paradigm shift in how firefighters are deployed and how their recovery times are prioritized before healthier patterns will emerge. For now, Brooks said, he would be happy to see firefighters begin prioritizing their own lives over the structure or property they are focused on saving.

"You can grow trees back, you can rebuild homes but you can't replace lives," Brooks said. "This is not an academic exercise - our goal in publishing is to save lives."

Scott Jackson can be reached at (208) 883-4636, or by email to sjackson@dnews.com.