Providing support beyond the textbook

Forestry researcher makes use of mental health training in classroom

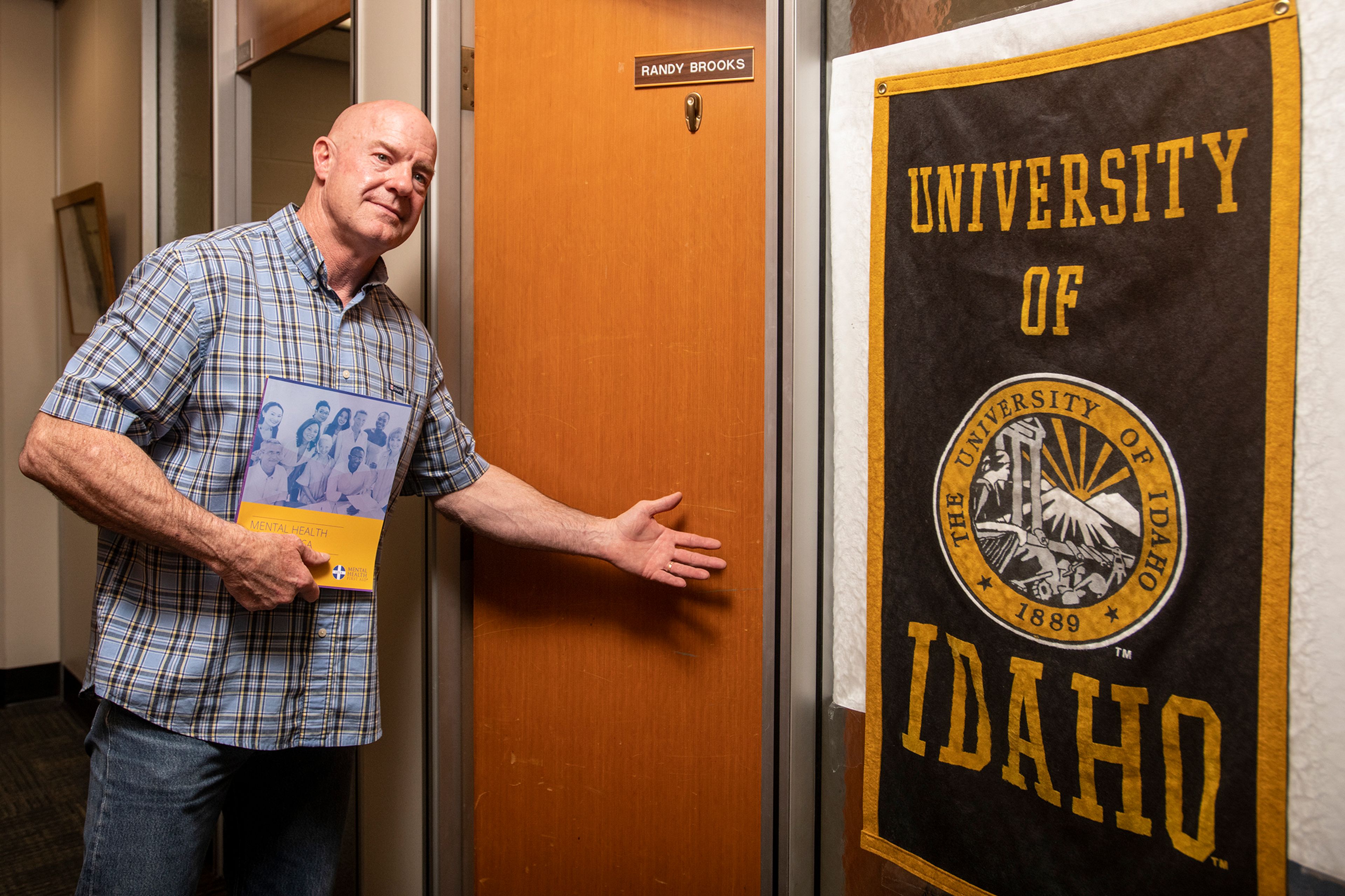

As a professor and extension forestry specialist at the University of Idaho, Randy Brooks never had an academic focus in behavioral health. He’s the poster child for the university’s College of Natural Resources, not a psychologist — and yet, over the past year, Brooks said he often found himself providing mental health support to students in his classes.

Despite having no formal education on the subject, Brooks’ interest in mental health was piqued years earlier while researching the health impacts of sleep deprivation on wildland firefighters.

Brooks, whose own son is a smoke jumper, also knows that wildland firefighters are at a greater risk of depression, anxiety, PTSD, binge drinking and excessive alcohol consumption. When he got the chance to certify as a Mental Health First Aid instructor along with 13 other extension educators, he jumped at the opportunity.

“I looked at that as my next step, a stepping stone into the research I’ve been doing,” he said. “Because they all play hand-in-hand.”

Much like the name suggests, Mental Health First Aid teaches people tools to provide support to someone who is experiencing mental health challenges or a mental health crisis, similar to how regular first aid addresses physical ailments.

Because of the pandemic, it took a year until Brooks and the other extension educators were able to begin their training for groups including Forest Service personnel, wildland firefighters and loggers. But as they did, Brooks saw something else was happening: more of his students were withdrawn in class, or they had stopped attending altogether.

Part of Mental Health First Aid, Brooks said, is being a “noticer.” Over the course of the pandemic, he noticed more students — specifically freshmen and sophomores — were struggling.

Greg Lambeth, the executive director of Counseling & Testing at UI, said that fits with what researchers have found when looking at pandemic-era mental health impacts.

“What they’re finding there is that some age groups are much more impacted by this pandemic than others. And 18 to 24 year olds are one of the most impacted groups,” Lambeth said. “The other age cohort is the one right before that, 12 to 18 year olds, and and in that cohort, women in particular, because they often have to look at gender as well.”

Even before the pandemic, more young people reported mental health challenges each year. A report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed a steady increase in teenagers who said they felt sad or hopeless, or seriously considered or planned suicide between 2009 and 2019.

Brooks, who’s been with the university for more than 30 years and has spent more than a dozen of those years on campus, said he’s never seen it as bad as in the past year.

In his classes, all his students have his cell phone number. When he notices a student has become withdrawn, or stops participating or attending class, he checks in with them. This showcases the importance of a Mental Health First Aid instructor’s role as a “noticer.”

“I had 28 (students) in my class this semester. Six of them I was having check in with me at least on a weekly basis,” he said. “Some I was touching base with almost every day. Last fall, out of 128 (students), I would say, maybe a dozen to 15 (were checking in).”

Brooks also refers his students to the university’s counseling and psychiatric services, which provides free mental health support to undergraduate students and some graduate students.

Their clinic has seen an increase in students each year, Lambeth said, as well as an increase in students requesting a mental health-related medical withdrawal. The number seeking testing for learning disabilities, particularly ADHD, has more than doubled.

“Year over year, both in terms of the number of students that we’re seeing, and in terms of the overall number of sessions that we see, (there’s an increase),” he said. “But not by huge amounts.”

Although there has been an increase, the center’s average wait time for new appointments has been about a week, Lambeth said, which is relatively short compared to other counseling centers, and better than in years past. The center also has walk-in hours and an after-hours services.

They currently employ seven full-time psychologists, the equivalent of two full-time social workers, a psychiatric nurse and four doctoral students in an accredited training program. The counseling program is also looking to hire another full-time psychologist and a master’s-level clinician, Lambeth said.

Though the counseling center is a resource to students, it’s not the only one, Lambeth said. UI is now a pilot location for Mental Health First Aid training, and the interest in discussing mental health from both students and staff has been unprecedented, he said.

Sometimes, talking with professors or peers that students know is also more accessible to them than going directly to the counseling center. In Brooks’ case, some students who aren’t comfortable going to the counseling center are more willing to talk to him.

“I had a (student) that came to me and said (they were) struggling with some issues. And I recommended going to the counseling center up here,” he said. “(Their) response was, ‘Randy, I’m not going to spill my guts to a stranger. You’re my teacher. I’ve developed a working relationship with you and I know that I can trust you with what I tell you.’ ”

Many universities, including UI, are moving toward providing more campus-wide mental health support systems for students, Lambeth said. Enlisting faculty and staff is an important step in meeting those needs.

“I think that’s really important,” he said, “that we are interacting with faculty and staff on campus (and) providing them the support and training that can help us to identify students who are in distress.”

Sun may be contacted at rsun@lmtribune.com or on Twitter at @Rachel_M_Sun. This report is made possible by the Lewis-Clark Valley Healthcare Foundation in partnership with Northwest Public Broadcasting, the Lewiston Tribune and the Moscow-Pullman Daily News.