‘There’s going to be a day of reckoning’

Analysis

In December 2019, as word first arrived about a novel virus in China, Congress passed the final component of the federal budget and went home for the holidays.

The $1.4 trillion discretionary spending plan included money for the military, the legislative branch and most executive branch agencies. Mandatory programs such as Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid were funded through other mechanisms.

As they had done in previous years, lawmakers again sidestepped the budget caps they enacted in 2011 — fiscal handcuffs that were meant to restrain their own deficit spending.

The 2019 bill exceeded those caps by $320 billion. By the end of the year, the total federal debt topped $22.6 trillion — up more than $7.9 trillion, or 54%, since 2011.

Twelve months later, amid a global pandemic, the debt had ballooned by another 19%, or $4.23 trillion — the largest one-year increase in U.S. history and more debt than the nation had accumulated during its first 217 years of existence, from 1776 through 1992.

The enormous size of the 2020 deficit raises questions, not only about Congress’ ability to manage the budget, but about the long-term stability of federal finances. If the trend continues, could the government eventually be at risk of defaulting on its obligations?

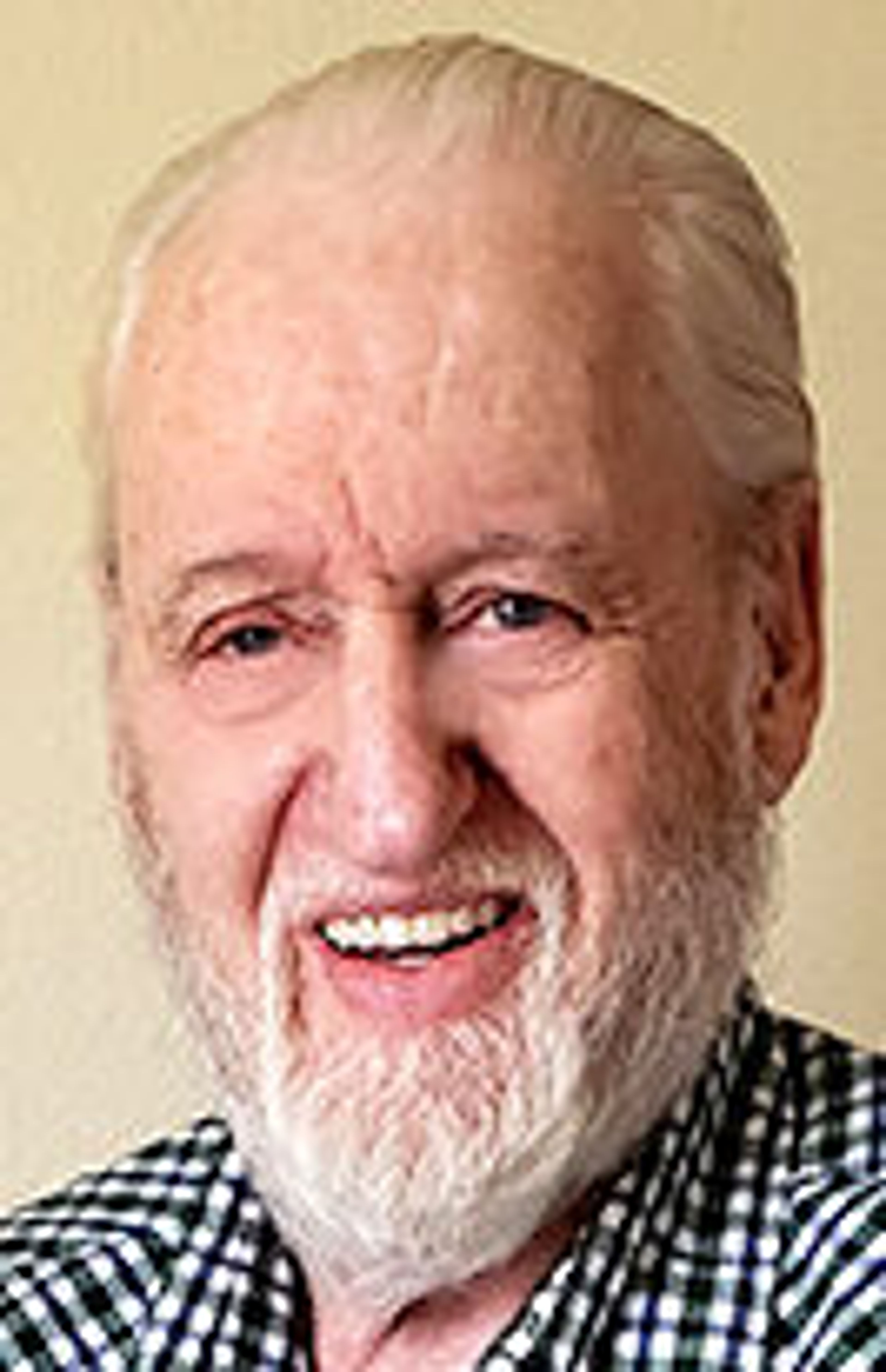

“In my experience, I’ve had to pay back everything I’ve borrowed,” said Scott Bedke, Idaho’s lieutenant governor-elect, during a visit to Lewiston in September. “I assume the same is true of governments. I assume there’s going to be a day of reckoning.”

Both parties guilty of deficit spending

For decades now, Americans have voiced concerns about their government’s spendthrift ways. They worry about the solvency of Social Security and Medicare, about burdening future generations with crushing debt. They worry about runaway inflation, and wonder who’s going to pay for it all.

Although many members of Congress share those concerns, neither party has demonstrated much leadership in addressing the issue.

During the Trump administration, for example, Republicans enthusiastically supported a president who was more intent on cutting taxes and making sure his name was on stimulus checks than in balancing the budget.

Democrats have done their part as well, adding another $4.47 trillion to the national debt over the past two years – bringing the total up to $31.37 trillion as of Nov. 28.

Congress might not be as amenable to deficit spending in the coming year, though. Having won a slim majority in the Nov. 8 general election, House Republicans are in position to challenge President Joe Biden’s fiscal priorities.

For the first time in at least six years, the federal debt may be in the crosshairs.

Newly elected House Republican Leader Kevin McCarthy suggested as much in an October interview, saying he would consider using the federal debt limit as a negotiating tool to demand future budget cuts.

“If people want to (increase) the debt ceiling, it’s just like anything else,” he said. “There comes a point where, OK, we’ll provide you with more money, but you have to change your current behavior.”

‘We went to D.C. specifically to cut the federal deficit’

This same scenario has played out before, though, with limited success.

In 2011, Tea Party-inspired Republicans came into the session intent on reining in federal spending. Having picked up 63 seats in the House in the 2010 election, it was their best chance in a generation to force a permanent change.

“There was a group of us who were fiscal hawks. We went to D.C. specifically to cut the federal deficit,” said Idaho attorney general-elect Raul Labrador, who in 2010 was elected to the first of his four terms representing Idaho’s 1st Congressional District.

To enact that change, GOP lawmakers targeted the federal debt ceiling.

The debt ceiling, or debt limit, caps the amount of money the U.S. Treasury can borrow. It has no relationship to spending, but does determine whether the government has the funds to pay its bills.

Historically, raising the debt limit was never particularly controversial, regardless of which party was in the majority or who was in the White House.

In 2011, though, House Republicans said they wouldn’t approve another increase unless it was tied to spending cuts and fiscal reforms — including sending a balanced budget amendment to the states for possible ratification.

“There was a pretty heated fight within the (House Republican) Conference,” Labrador recalled. “Some members didn’t think we should use the debt ceiling as a negotiating tool. We said, ‘No, that’s the only thing we can use. It’s the only thing (Democrats) will listen to.’ For us, it was do-or-die.”

Congress opts for ‘a small solution’

To resolve the standoff, Labrador and others proposed the “Cut, Cap and Balance Act,” which would immediately cut spending by $111 billion and cap future expenditures at 19.9% of GDP by 2021. The bill also included a balanced budget amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Although the House passed the measure 234-190, it was tabled in the Senate.

The disagreement highlighted fundamental differences in the parties’ fiscal priorities. Democrats, in general, were willing to cut military spending and raise taxes on the wealthy, but insisted on protecting social programs. Republicans took the opposite tack, targeting social programs while pushing for higher defense spending and tax cuts.

At the time, more than a third of the federal budget relied on borrowed money. The annual deficit was more than $1.2 trillion — nearly as much as the entire discretionary budget. Financial markets worried if lawmakers failed to resolve their differences, America would default on its debt and cause a global economic meltdown.

On July 31, two days before the government ran out of money, Congress finally cut a deal: In exchange for raising the debt ceiling by $900 billion, spending would be cut a similar amount over the next decade. The House and Senate would also vote on a balanced budget amendment, and establish a joint commission to craft additional debt reduction legislation by the end of the year. If that legislation wasn’t approved, then automatic, across-the-board spending caps would be implemented, affecting both defense and nondefense spending.

Although the deal averted the immediate crisis, Standard & Poor’s downgraded the federal government’s credit rating for the first time in history. The agency specifically cited the “material risk that U.S. policymakers might not reach an agreement on how to address medium- and long-term budgetary challenges.”

Following the downgrade, the stock market tanked, losing 10% of its value in the space of a week.

For fiscal hawks like Labrador, the deal was a major disappointment.

“I felt like it was a small solution,” he said.

For example, while the agreement temporarily slowed the growth in federal spending, it didn’t cap future expenditures as a set percentage of GDP.

And rather than abide by across-the-board spending caps that were implemented later that year, Congress regularly sidestepped them until they expired in 2021.

The deal also required Congress to vote on a balanced budget amendment, but not to pass one and submit it to the states for ratification, as conservatives had wanted.

The amendment ultimately fell 23 votes short of the two-thirds majority required in the House and failed in the Senate.

‘Those were the battles that created the House Freedom Caucus’

Perhaps the most lasting legacy from the 2011 standoff, though, was the rift it caused within Republican ranks.

GOP leaders felt the showdown had damaged the party’s reputation, leaving voters upset. Consequently, during subsequent debt limit standoffs in 2013 and 2015, they looked for ways to avoid prolonged fights.

Fiscal hawks, by contrast, felt this was an issue Republicans could stake their future on. They wanted party officials to play hardball — and when that didn’t happen, they eventually forced a change in leadership, ousting House Speaker John Boehner.

“Those were the battles that created the House Freedom Caucus,” said Labrador, who co-founded the conservative group in 2015. “We were frustrated. We came to D.C. to do something. We wanted to change the way Washington works and change the way Congress spends money. But we saw our leadership caving on issues and coming to the wrong conclusions.”

Another unforeseen consequence of the 2011 standoff was the practice of simply suspending the debt ceiling — ending the brinkmanship before it began and removing any deadline pressure that might force lawmakers to work together on long-term solutions.

The debt ceiling was suspended for the first time in February 2013. It was reinstated three months later, retroactively authorizing all the new debt that had been added in the interim.

Beginning in October 2013, debt ceiling suspensions became commonplace. Over the following eight years, until August 2021, the debt limit was actually suspended 80% of the time — including the entirety of 2020. During that period, a total of $12.3 trillion in new debt was added, essentially without congressional oversight.

Since it was reinstated last year, Congress has lifted the debt limit two more times, most recently in December. It now stands at $31.38 trillion.

It’s unclear if Republicans are interested in reducing debt

With actual debt now at $31.37 trillion, McCarthy and House Republicans may not get the chance to use the debt limit as a negotiating tool during the next session of Congress.

Democrats are talking about raising it before the end of this year, while they still have a majority in both chambers. That could postpone any showdown for at least another year.

Moreover, even if Republicans succeed in forcing a standoff, it’s unclear if they really want to reduce the debt or just cut spending.

Shortly after the Nov. 8 election, for example, McCarthy said the first thing House Republicans plan to do next year is repeal the $80 billion Democrats recently approved for the Internal Revenue Service.

That money would be used to hire thousands of new IRS employees over the next decade, giving the agency the manpower needed to track down some of the estimated $600 billion per year in taxes that people owe but refuse to pay.

Similarly, party officials have said they want to make the 2017 Trump tax cuts permanent. Several major provisions of that $1.9 trillion bill are scheduled to expire in 2025.

Despite conservative rhetoric about the benefits of tax cuts, that approach has done nothing historically to help balance the federal budget or reduce the national debt.

Consequently, as was the case in 2011, the mammoth debt could once again wriggle out of the crosshairs. A new showdown between Republicans and Democrats may do nothing to stem Congress’ addiction to deficit spending or reverse the tide of red ink.

Spence may be contacted at bspence@lmtribune.com or (208) 791-9168.

Editor’s note: This is the first of a two-part series regarding the federal debt. Today’s story looks at the 2011 debt ceiling standoff in Congress, and the possibility for a repeat next year. Part II will appear in online Sunday at dnews.com and addresses whether the debt has reached dangerous territory.