Nearby History: Wheat on the Palouse: A union of farmers and scientists

"We have been astonished today at the luxuriance of the grass and the richness of the soil," wrote Isaac I. Stevens, governor of Washington Territory, in his journal in June 1855. He accompanied his words with a drawing of the Palouse hills. But the potential of those hills for agriculture was not discovered immediately.

The first settlers looked for flat places along the creeks to establish their homesteads. One early settler recalled riding for "days and days over thousands of acres looking for land which was level enough to grow wheat." The first farming economy on the Palouse Prairie was cattle ranching, followed by sheep farming. Not until the 1870s did farmers realize that the soil of the steep bunchgrass-covered slopes could grow an excellent cash crop of wheat.

The Palouse is uniquely suited for growing unirrigated wheat because it has excellent soils and a Mediterranean climate - cool and moist in winter and dry and hot in summer. But when farmers began growing wheat they still had to learn how to adapt to local conditions. For example, in the lower rainfall areas farmers learned to follow a cropping year with a summer fallow to collect moisture in the soil, and to plant seeds more deeply so the germinating plants could reach the soil water. The development of a new type of seed drill made deeper planting possible, which led to a need for new wheat varieties that could emerge strongly from deeper planting.

As farmers developed appropriate cultivation methods they also discovered a need for varieties of wheat with different properties, including resistance to diseases such as wheat smut, bunt and rust. Wheats with better adaptation to the climate were also needed.

Winter wheat varieties (planted in the fall) need to be able to germinate when fall rains come, survive freezing and grow well to minimize winter erosion, yet not grow so tall the next spring that they tend to fall over (lodge) or the grains scatter too quickly (shatter). Spring planted wheat needs to germinate and grow very quickly to produce grain in the short summer season.

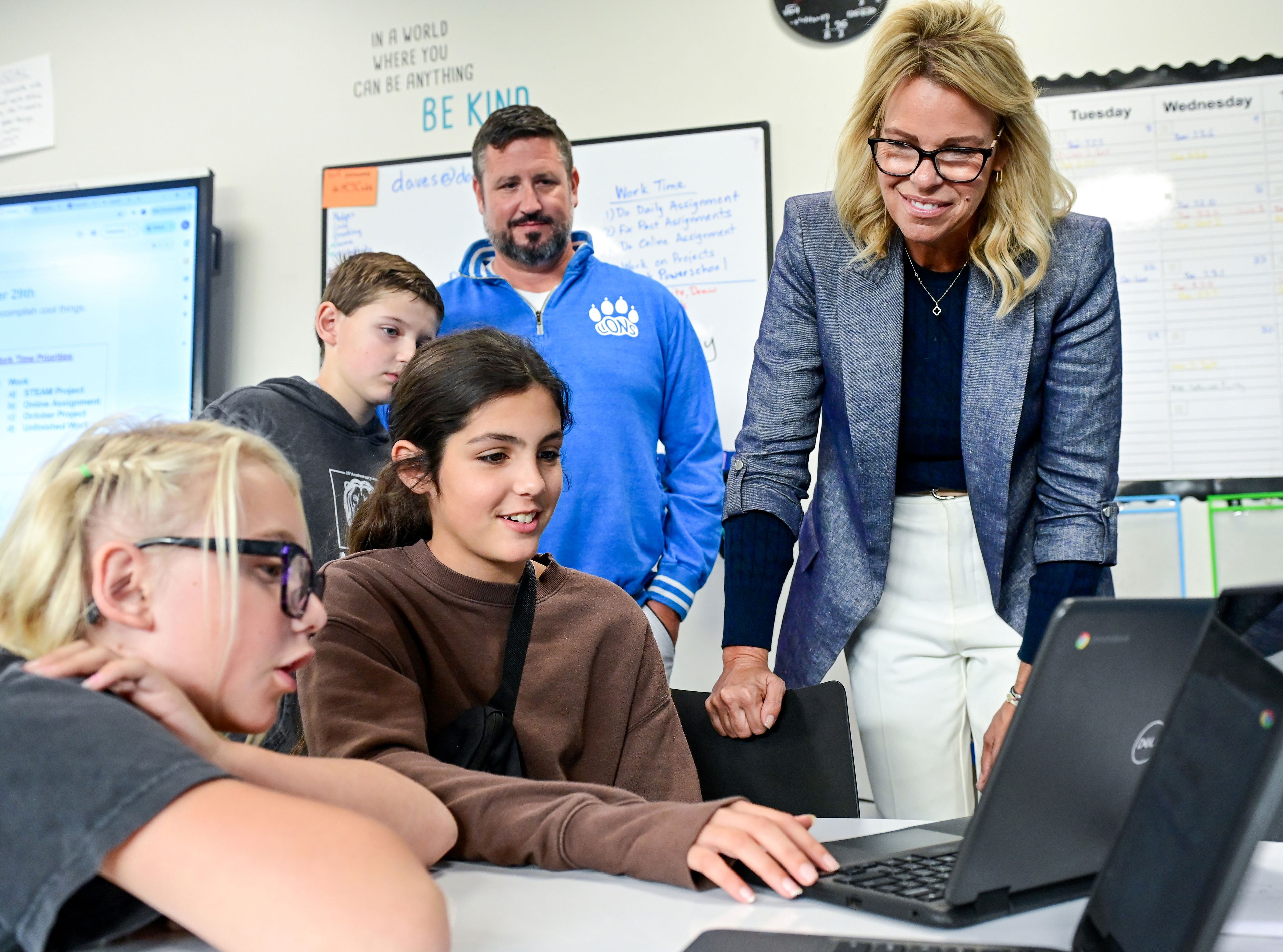

The partnership between farmers and wheat researchers began with the establishment of agricultural experiment stations in Pullman and Moscow in 1891 and 1892. Farmers were initially dubious about "outside experts," but came to appreciate the benefit of increased yields and higher quality crops from the new varieties.

W.J. Spillman, who taught at Washington Agricultural College and School of Science (now Washington State University) from 1894-1902 is credited with pioneering the breeding and genetics that led to the development of varieties better adapted to the regional climate and soils. Hired to improve the economic health of farmers, he spent a lot of time in the field listening to their needs, as wheat breeders in this region still do today.

Renowned wheat breeder Orville Vogel came to Pullman in 1931 and was part of the wheat research team at WSU and the U.S. Department of Agriculture until he retired in 1973. He developed the semi-dwarf soft white winter wheat varieties, Gaines (introduced in 1961) and the improved Nugaines (1962), which increased yields by up to 25 percent.

Well-known Pullman breeder Bob Allan, now retired, worked for many years improving club wheat, a dwarfing type valued for its high quality. Asian markets, which have the largest share of the international market for Palouse wheat, value club wheat for the properties it gives to products like pastries and Japanese sponge cakes.

Well-known University of Idaho breeders include the late Warren Pope, and Bob Zemetra, now at Oregon State.

Current trends including breeding for varieties better adapted to a warmer, less predictable climate and varieties better adapted to no till and low till cultivation. Breeding a productive perennial wheat is a long-term goal.

Technology has changed in a hundred years, but wheat breeders still work to meet the needs of wheat farmers.

Thanks to Arron Carter, co-holder of WSU's Vogel Endowed Chair in Wheat Breeding and Genetics, and Kurt Schroeder, UI cropping agronomist, for talking to me about the history of wheat breeding in our region.

Suvia Judd of Moscow is a small acreage farmer, caregiver and self-described "science geek."