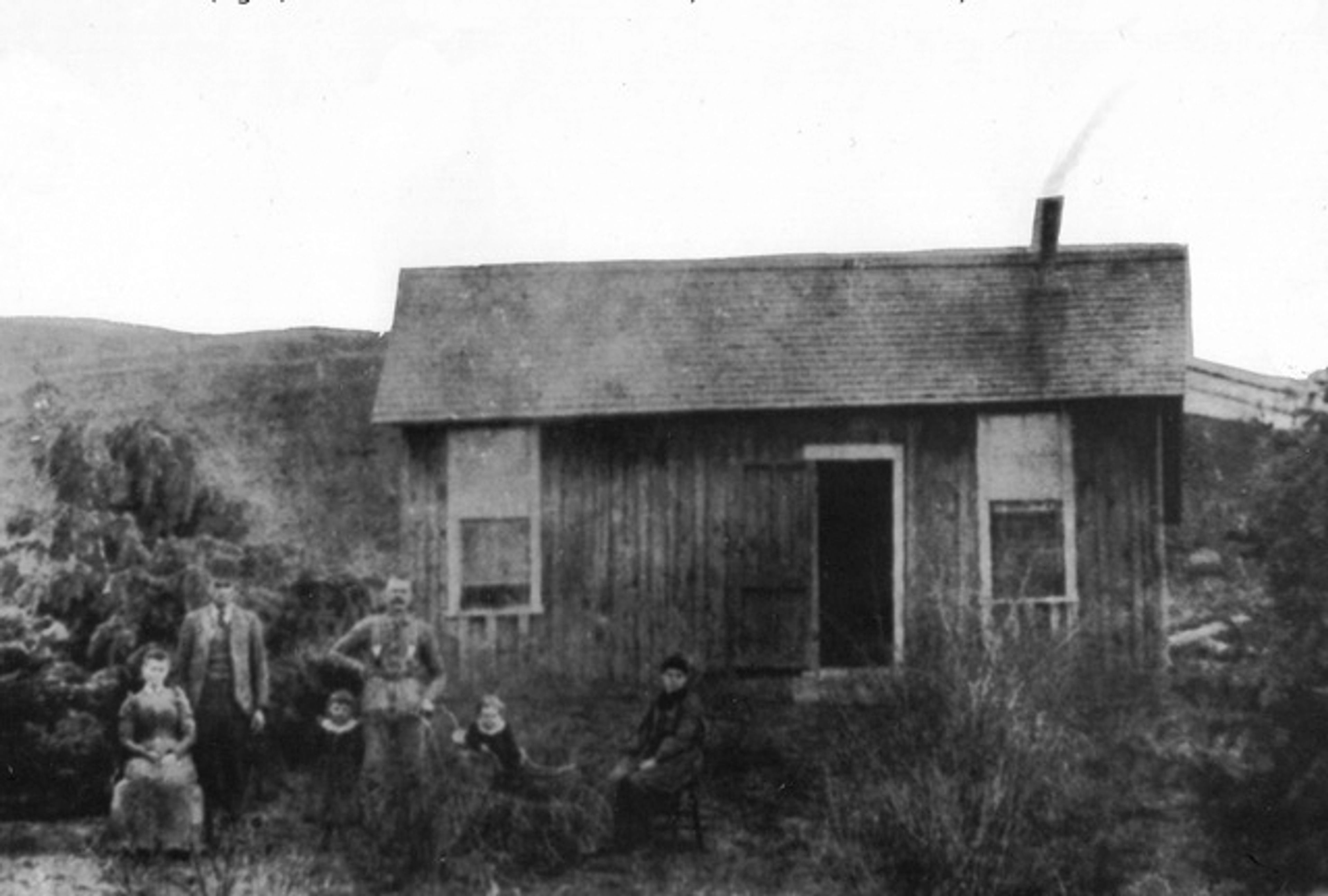

The Boone Homestead House: A Whitman County staple since 1878

Nearby History

Although not the first house built along Union Flat in southern Whitman County, the Boone Homestead House is one of the oldest still standing in that area.

It was built in 1878 by Daniel Wright Boone (1855-1936), who left Illinois in 1876 at the age of 21 with his older brother Reuben and wife Jane (nee Williams) to live in Oregon. Dan moved to Washington Territory a year later, where he lived for two years on Union Flat with his sister Sarah Jane Farnsworth, her husband Volney and their three children.

In 1879, at his sister’s urging, Dan filed a timber culture claim on 160 acres a few miles down the road from the Farnsworth place. Two years later, he purchased an additional 160 acres for $200 under the Preemption Act. He also acquired 80 acres under the Homestead Act, for a total of 400 acres.

He improved his land by growing wheat, planting a large orchard, raising cattle, building a barn and fences, and constructing a board-and-batten homestead house that measured 24 by 16 feet — 384 square feet. He “proved up” his homestead on Sept. 11, 1884.

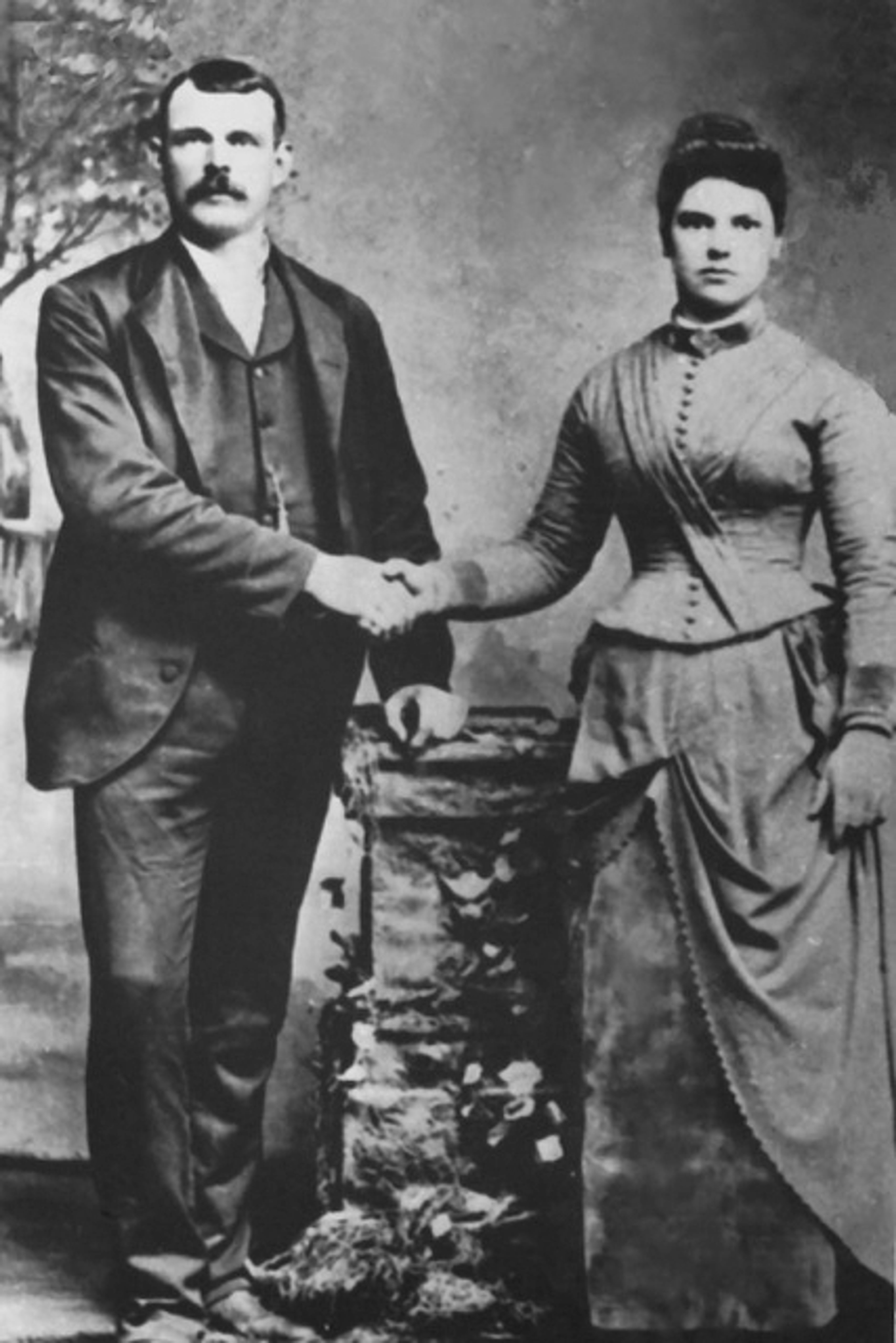

Five years later, Dan briefly returned to Illinois to find a wife. He immediately began courting Amelia Fernanders Williams (1870-1963), his brother Reuben’s 18-year-old sister-in-law. They were married in January of 1889. In March, along with another of Dan’s brothers, George Washington Boone, and his new bride Georgia Brummet, they headed west on an “immigrant train.”

Not long after the newlyweds’ arrival on Union Flat, Dan put the house on skids and moved it with horses down the hill on which it had originally been built so that he could pipe running water inside — a luxury very few rural families had at the time.

The Boone Homestead House was sometimes home to as many as 15 people. In 1889, it housed two married couples and a bachelor — Dan and Amelia, George and Georgia, and their friend Ed Hough, who had traveled west with them. Over the next 20 years, nine children (seven girls and two boys) were added to Dan and Amelia’s family. Additionally, they somehow found room to board a schoolteacher from the nearby Beauridell School.

Instead of building a new, larger home, however, the family simply attached new rooms and even connected a free-standing building to the original house.

The first room added, a kitchen, was followed by a large, rock-walled root cellar that was dug into a bank behind the house, as significant space was needed to store the food necessary for so many people. Next, a room was built above the cellar for a bedroom.

Eventually, the house and cellar were connected by a screened porch, and the attic of the cellar/bedroom was finished for more sleeping room. It was common for the Boone children, when on their way to bed, to say goodnight to their parents by announcing that they were going off to “China Town” because it seemed so far away from the rest of the house.

Finally, Dan and Amelia built a big woodshed next to one end of the house, but it was never used to store wood and was instead upgraded and turned into a bedroom. The attic above it served as Amelia’s bedroom after Dan’s death, after which her youngest daughter and her husband took over the farm.

The Boone Homestead House did not have a modern bathroom until the early 1940s — an outhouse had sufficed for decades. As was the custom in most rural homes, baths were taken once a week in a portable folding canvas tub in the kitchen, with the bathwater being shared by a number of people before it was changed. Like their neighbors, the house did not have electricity until the 1940s, when the Rural Electrification program finally reached them.

Located off the Wawawai-Pullman Road, near the Boone Oak Grove, the house now sits empty. The farm has been owned by the Boone family since 1879 and was placed on the list of Washington Centennial Farms in 1979.

Meyer taught history at Washington State University for 25 years. She has been active in Whitman County Historical Society since 1992.