A school funding X factor: the wording

Terminology used in an Idaho pandemic policy could work against many schools

After the 2023 legislative session, one of the most pressing issues on school leaders’ minds isn’t a new law.

Instead, it’s a school policy issue all but absent from the session’s debates, votes, and vetoes — that of whether school funding should be based on student attendance or enrollment.

What seems like a wonkish bit of policy actually has a major impact on schools because it determines how much funding they get from the state.

The issue hearkens back to the height of the pandemic. At that time, the State Board of Education temporarily based school funding on enrollment instead of attendance — numbers that were especially volatile, due to remote learning, school closures, increased illness and other COVID-19 complications.

Since 2020-21, enrollment has dictated how much money schools get each year. But that time has come to an end.

In many cases, it means schools and districts will get less money than they anticipated, starting next school year.

But they’ll also get an influx of cash — such as $100 million to spend on property tax relief; $100 million for classified staff pay raises; and $145 million for teacher pay raises.

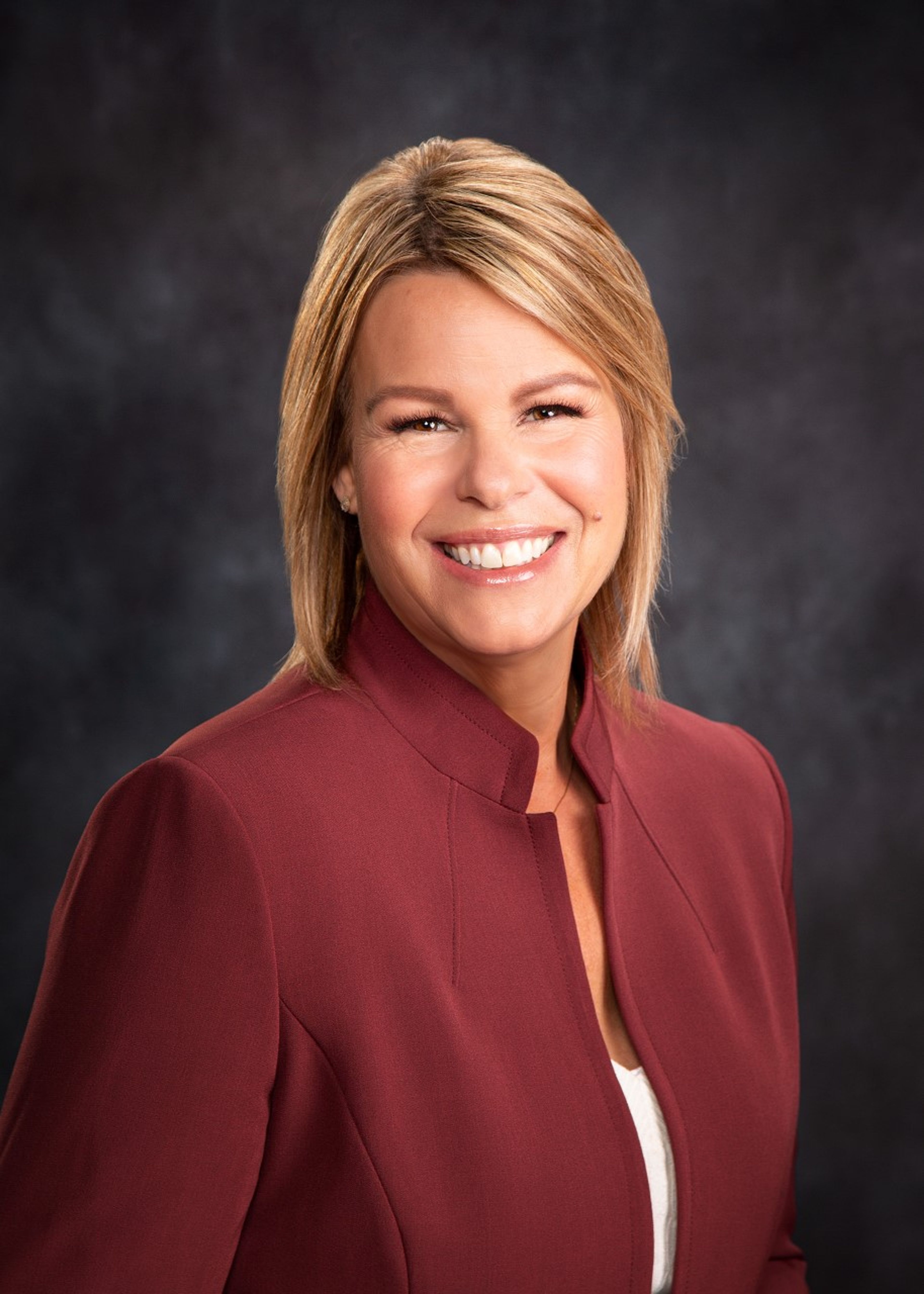

At a legislative roadshow in Pocatello on Wednesday, state superintendent Debbie Critchfield encouraged education leaders to be creative when closing funding gaps. That might mean drawing on rainy-day savings or federal COVID-19 dollars.

But she cautioned that districts should not pull from money intended for teacher and staff raises to make up the difference.

“The last thing we want to hear are teachers who say, ‘We never got any of the raises we were supposed to get,’” Critchfield told EdNews. “We don’t want that.”

For the coming school year, districts and schools will have to make do with the less-than-anticipated funds they receive.

“We recognize what you’re up against,” she told the room full of education leaders.

The state board meets next on April 25 and 26, when members will likely vote to extend enrollment-based funding through July (the end of the current fiscal year).

But the state board will not extend enrollment-based funding any further (like it’s done since the pandemic). That temporary, Band-Aid style solution that’s been used in times of crisis is no longer appropriate, Critchfield said.

“We need to change the funding (formula) rather than come through a side door,” Critchfield said. “Let’s have the fix, let’s have the right solution.”

This summer, she plans to work on reinventing the formula in a way that better suits schools (and do so in time for the next legislative session). That way, maybe by this time next year, school leaders will be celebrating a new and improved attendance-based funding policy.

Until then, here’s what a return to pre-pandemic, attendance-based funding system means for Idaho schools.

Statewide, school leaders love enrollment-based funding.

At an Idaho School Boards Association conference last summer, more than 7,000 members voted in favor of a permanent turn away from attendance-based funding (only one nay vote was cast).

“Enrollment-based funding removes the uncertainty and instability districts face in the funding they will receive from the state … especially since the COVID-19 pandemic began and daily absences have significantly increased,” the adopted resolution reads.

But after this session, when no lawmakers entertained an effort to make the change permanent (and after last session, when Gov. Brad Little vetoed a bill to do just that), it’s clear that education leaders will have to accept that attendance-based funding isn’t going away.

“That will have a dramatic impact on us in terms of staffing,” Brady Dickinson, the Twin Falls superintendent, said earlier this week. “If we go back to ADA, we’re going to have to reduce somewhere around 35 teacher/counselor positions.”

That means instead of filling openings, Dickinson may have to eliminate those positions — which would directly impact students.

Part of the problem is that prior to the pandemic, average daily attendance hovered around 94-95%, Dickinson said. Right now, that number is more like 90 to 92%.

“Every percentage is a big difference, and so we’re pushing to get those attendance rates back up,” Dickinson said.

But at the same time, the pandemic brought about a social shift where parents are more likely to keep their kids home when they’re sick, at district officials’ urging. But now, school districts stand to get less funding because of that.

Some might argue that tying funding to attendance is a necessary incentive to get school leaders to prioritize getting and keeping kids in class, but Dickinson said good attendance leads to high achievement, so that’s incentive enough.

Gary Tucker, the superintendent for Marsh Valley School District, said his district is distinctive in that it doesn’t have any ongoing bonds or supplemental levies. That means their budget is even tighter with less room for cuts.

“We run pretty lean already,” he said.

Tucker hopes some of the extra school funding will offset the losses from a return to Americans with Disabilities Act funding. The drawback is that the new influx of money may not go toward new programs it was intended for.

“We’re going to have to use that money to take care of our existing programs,” he said.

Spencer Barzee, superintendent of the West Side School District, said the switch could mean a loss of up to $300,000 for his schools.

“I don’t know where it’s going to come from at this point,” he said.

Jonathan Gillen, the chief operations officer for West Ada School District, said it’s a busy time to be creating school budgets. He now has just weeks to digest legislative changes, adjust the budget for next school year, and be ready to present his findings to the school board.

“It’s a very short timeline,” he said.

This story is from Idaho Education News, a nonprofit supported on grants from the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson Family Foundation, the Education Writers Association and the Solutions Journalism Network.