Humbled by history; lawmakers honor 100th anniversary of Idaho Statehouse

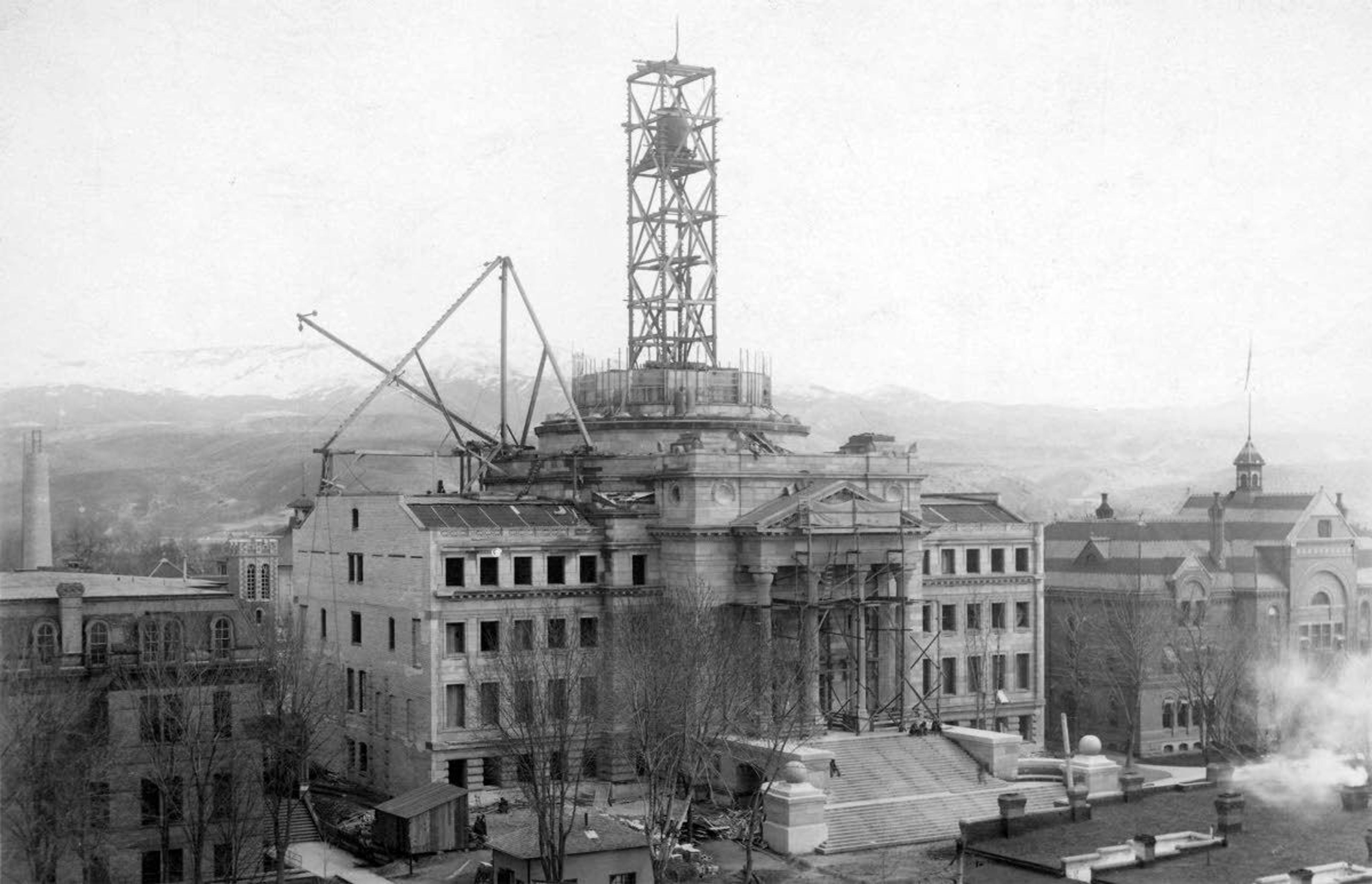

BOISE — It was a boondoggle from the start, this great domed edifice meant to demonstrate a people’s pride in a state that was still being carved from the wilderness.

There were accusations of bribery and backroom deals, and huge cost overruns. There were public hearings to investigate claims of mismanagement and extravagance.

It took 15 years to finish the job, and could have taken even longer had not thousands of returning soldiers needed work.

Nevertheless, a century after construction of the Idaho Statehouse was completed, there’s no doubt the “Capitol of Light” has lived up to architect John Tourtellotte’s original vision.

Tourtellotte designed the building to be the physical manifestation of Idaho’s soul, the moral heart without which no individual or government could endure.

“The great white light of conscience must be allowed to shine, and by its interior illumination make clear the path of duty,” he said. “In the clarity of that vision, (the people) must act and go forward with courage. … If the people of Idaho hold these ideals and are striving to make them real, then this capitol truly represents the commonwealth.”

Although Tourtellotte saw light to be the signature characteristic of the building, the gravity of the place is what stands out for most lawmakers. It weighs on them. It is a daily reminder to do good.

“I’m still humbled every time I walk into the building,” said Rep. Caroline Troy, R-Genesee. “When you get to the point where walking into the Capitol isn’t an exciting, thrilling moment, maybe it’s time for you to pack it in.”

Among the many bills Troy introduced this session was a resolution honoring the 100th anniversary of the Statehouse. It notes that, since the building was dedicated on Jan. 3, 1921, it “has served as the People’s House, providing a home for discussion, cooperation, collaboration and the conduct of the people’s business.”

Speaking in support of the resolution, Sen. Grant Burgoyne, D-Boise, said the Statehouse is a reflection of Idaho’s state motto, “Esto perpetua,” or “let it be eternal.”

“To me, this building has always been a statement from — maybe not the pioneer generation, but let’s say the pioneer generation-and-a-half,” Burgoyne said. “It says we came to stay. It says we aren’t just visiting; it is perpetual. We’re staking our claim.”

Coming to the Statehouse as a representative of the people is a “pinch me” moment for many lawmakers.

“I come in at night and look up at the dome and think, ‘How did this little girl from the other side of the tracks ever have an opportunity to serve in this building?’” said Sen. Patti Anne Lodge, R-Caldwell. “I’m just so grateful.”

Rep. Charlie Shepherd, R-Pollock, had been to the Capitol to visit his father, former Rep. Paul Shepherd, but it was a different experience entering the building as an elected official himself.

“I remember feeling instant awe,” Shepherd said. “I understood the magnitude of what the building meant. It enhanced my appreciation for what we’re doing here, for the laws we make.”

That wasn’t the universal reaction, though, as the Statehouse rose from the ground. The project was embroiled in controversy from its very beginning.

Construction began in 1905. Tourtellotte’s initial cost estimate was $800,000, but the Legislature only appropriated $350,000. Within four years the price tag had soared to $1.8 million.

The sale of 30,000 acres of state timberland was supposed to bring in $600,000, allowing most or all of the building to be completed without added public cost. It actually only raised $170,000. Sen. Weldon Heyburn tried to help out by getting Congress to grant Idaho another 95,000 acres of federal land, but was unsuccessful.

Even with the addition of $130,000 in state bond proceeds, construction had to be suspended in January 1909, for lack of funds. By that time, only two of the planned four floors in the central, domed complex had been completed.

The dismal situation prompted Sen. Ravenal Macbeth, a Custer County mine owner and leader in the Democratic caucus, to stand up on the floor of the Senate and charge the Capital Building Commission with “gross incompetence.”

Not only did the commission lack blueprints and building specifications, Macbeth said, it couldn’t even say what percentage of the structure had been completed and had no clue about projected costs.

“The (commission) has been extravagant in its mismanagement,” he said in a 1909 Senate State Affairs hearing. “The ultimate cost of the capitol building now in construction will be so great … as to be limited only by the patience and endurance of the taxpayers of the state.”

The Republican majority, incensed by Macbeth’s claims — and by the “sensational” news coverage it inspired — demanded he provide “a full and detailed statement” backing up his assertions.

To their chagrin, he did just that. Citing the commission’s own reports, as well as records from the state treasurer and comments by Republican Gov. James Brady, Macbeth defended his contention that costs were spiraling out of control.

“Misrepresentations were made,” he said. The people were “willfully misled.”

Tourtellotte, a better architect than insult artist, dismissed Macbeth as “rattle-brained.”

Despite this sorry beginning, additional funds were secured and the central, domed structure was completed in 1912. It housed the Idaho Supreme Court, as well as legislative committee rooms. Floor sessions, however, continued to take place next door, in the old territorial capitol.

That remained the case until 1919, when lawmakers approved $900,000 in bonds to add the House and Senate wings. The effort was promoted as a jobs bill, needed for the wave of doughboys returning from Europe after World War I.

Highlighting a combative relationship with local government that continues to this day, the bond measure included a proviso requiring Boise to purchase the parkland area in front of the Capitol. The property, which cost about $135,000, had to be deeded to the state before work on the building would continue.

Boise voters agreed to the deal. The territorial capitol and Central School buildings, which bracketed the central portion of the Statehouse, were subsequently demolished and the new House and Senate wings added, just in time for the 1921 legislative session.

The final cost for the new Statehouse came in right around $2 million, not including the parkland. That at a time when Sears, Roebuck & Co. was selling two-story, three-bedroom mail-order homes (sans bathroom) for less than $1,000.

The golden eagle atop the Capitol dome is 208 feet high. It’s possible to climb up and touch it, although the last 20 feet or so are on a chain ladder said to be so unstable that the wind can blow it out over the abyss — while someone is on it.

Even getting up to the cramped, exterior parapet just below the eagle is an adventure. It’s accessed by two narrow spiral staircases — one that can be viewed from inside the rotunda, and a second that connects the inner and outer domes.

Public tours typically only go as high as the fourth floor. However, legislators, staff and guests can occasionally go up one more floor, into a long, rectangular room where the original brick construction is exposed.

Generations of lawmakers and pages have signed the bricks, some in pencil, others in ink or magic marker.

“The pages love it,” said Senate Sergeant-at-Arms Sarah Jane McDonald. “It’s probably the best thing they get to do. It’s something they can do that no one else can do.”

McDonald has worked in the Statehouse for nearly 20 years. Like many who work there, she loves the history of the place. She’s also dismayed by recent security upgrades that replaced historic door handles with new electronic keypads.

“You just think about having your hand on a doorknob that people have been touching for so long,” McDonald said. “We’re all spoiled. Where else could you work that’s as beautiful as this place?”

Former Lewiston Sen. Joe Stegner played a leading role in keeping the Statehouse as a center for legislative operations.

He remembers coming to Boise with his father and brother when he was about 10 years old. They went to a downtown sporting goods store to buy some ski equipment.

“I walked outside, looked up and saw the Capitol,” Stegner said. “It was right there. I was absolutely mesmerized.”

Years later, after he was elected to the Senate, Stegner arrived in Boise late one night for the freshman orientation meeting.

“I saw the Capitol all lit up and thought, ‘Tomorrow I’m going to be in there as an elected official,’ ” he said. “I couldn’t have been prouder. There was just an immense sense of gratitude to be able to participate in that, having the chance to represent the citizens and communities in my district.”

When he was elected in 1998, there was already a lot of talk about needing more legislative space. The small committee rooms in the Statehouse were often filled to capacity. Previous renovations had also blocked some of the shafts and skylights that illuminated the interior, making it the “Capitol of Light.”

The state subsequently acquired the old Ada County Courthouse across the street from the Statehouse. By 2005, lawmakers were set to approve a multimillion dollar project to demolish the building and construct a new “Capitol Annex,” with office and committee space.

“I thought we’d be making a big mistake if we didn’t renovate and expand the original building,” Stegner said. “If we didn’t keep it a working Capitol, it would turn into a museum.”

Shortly before the Senate debated the Capitol Annex resolution, Stegner and his daughter, an architect, put together some drawings showing options for an on-site expansion.

“Then I went onto the floor of the Senate and made my pitch,” he said. “In order to expand the existing Capitol, we had to kill the resolution.”

The measure failed on an 18-16 vote. The Legislature subsequently appointed a study committee to review the issue. In 2006, lawmakers approved what turned into a $122 million renovation and expansion, with underground atriums being added on the House and Senate sides.

“I thought of all the unnamed heroes who put this building up, that’s lasted 100 years,” Stegner said. “We needed another 100-year solution, and I wanted to be part of that.”

House Assistant Majority Leader Jason Monks, R-Meridian, wasn’t aware of the history of the expansion project, but he was happy lawmakers decided to stay at the Statehouse, rather than relocate activity across the street.

“I’m grateful for the vision,” Monks said. “Right now, having a building like this, it’s a working museum. If we weren’t here every day, I think it would fall into disrepair.”

Monks pointed to Arizona as an example of what could have happened in Idaho, had the annex been built.

The Arizona House and Senate moved out of the original Statehouse into new buildings in the 1960s. At the time, he said, people no doubt thought the architecture looked modern and impressive. Sixty years later, it might be a different story.

That isn’t a concern in Idaho, though, since the underground atriums preserved the proportions and architectural integrity of the original Statehouse.

“This building will never be outdated,” Monks said.

Spence may be contacted at bspence@lmtribune.com or (208)-791-9168.