Idaho cobalt mining: The costs of U.S. green energy

Rising over the River of No Return that winds through Central Idaho’s city of Challis, the dry landscape wrinkles with beige hills, beyond which the Salmon River Mountains mark entry into one of the largest wild areas in the contiguous U.S. Under its surface lies value attracting international interests.

During an October flight into the backcountry, forests of Douglas fir and lodgepole pine trees carpeted the higher elevations and softened the pointed peaks of this rugged land. Veins of golden cottonwood leaves that line creeks and shallow ravines revealed the autumn season in a region with volcanic origins, which has drawn miners for more than a century.

But the veins beneath this expanse juxtapose the pursuit for minerals critical to a green future with a history of environmental damage.

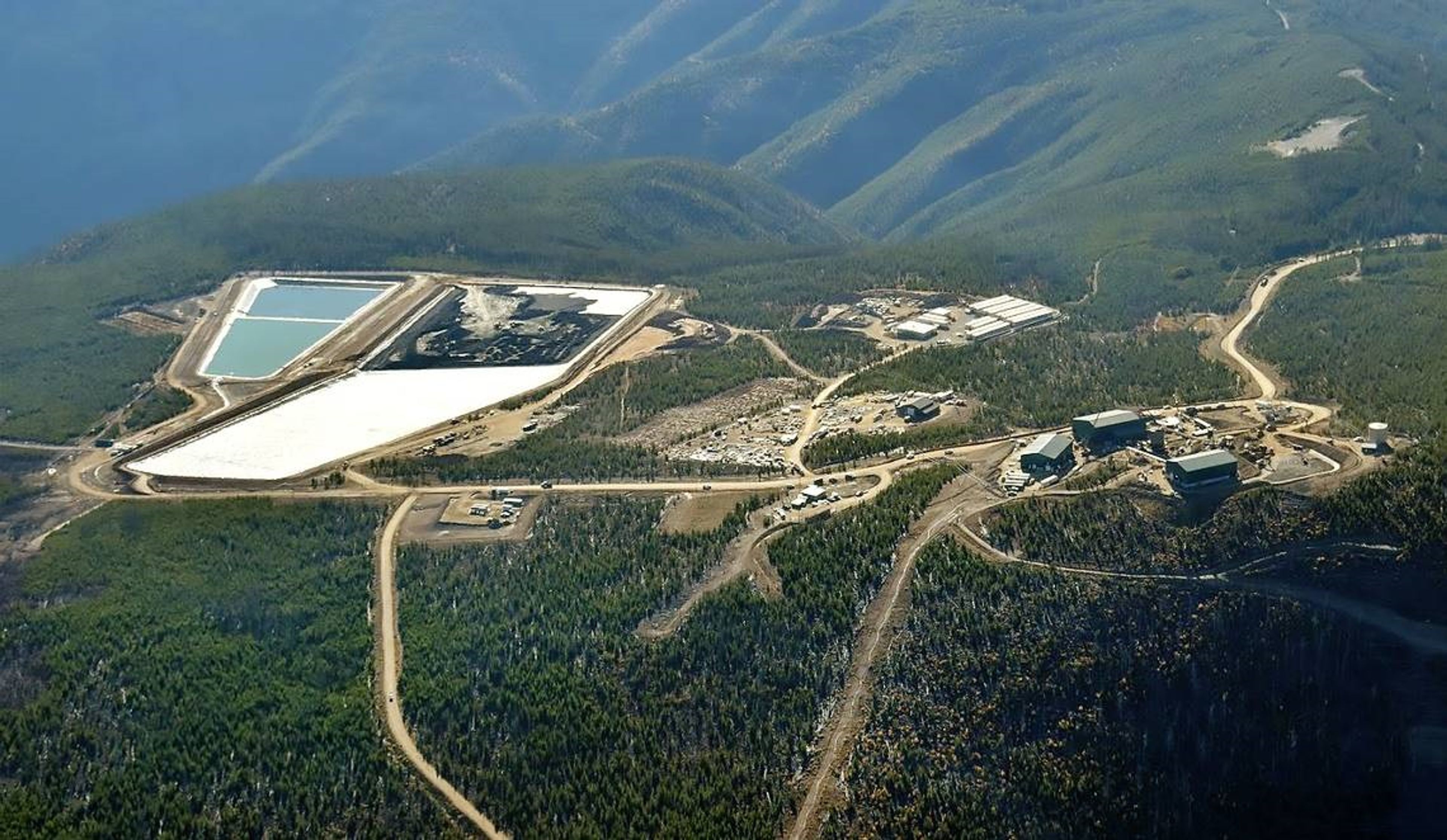

Jervois Global Limited, based in Melbourne, Australia, invested more than $100 million in a new cobalt mine northwest of Challis after buying it in 2019, with plans to soon begin hauling millions of tons of ore from the mountain. Starting early next year, the material will be processed into cobalt that could help power hundreds of thousands of new electric vehicle batteries each year in the U.S.

The enterprise has earned the attention of state and federal leaders, some of whom expect the mine to boost national security, while others hope it will assist in the country’s transition to renewable energy.

Cobalt mining is not new in Idaho or the U.S., but its production here has lain nearly dormant for decades. The industry’s reemergence is fueled by companies seeking to extract profit and a nation looking toward a sustainable future on which progressive policymakers say it has fallen behind. Meanwhile, critical resources for that future are controlled almost entirely by one of the U.S.’s leading global competitors.

In this new moment, some environmental groups see a need to compromise as they work to counter climate change, which they view as the existential threat of our time.

“The tools that we need to address climate change are many, but one of them is absolutely getting people into electric vehicles,” Justin Hayes, executive director of the Idaho Conservation League, told the Idaho Statesman. “And so it would be hypocritical for us to say, ‘Get into electric vehicles,’ but then not want to be a partner in finding ways of providing the minerals for society to get them.”

But procuring those minerals is not without its risks.

Jervois plans to pull pay dirt from the sloped peaks of the Salmon-Challis National Forest just north of the reclaimed remains of a once-toxic mine site.

Why cobalt?

North of Challis, near the city of Salmon, runs a deposit of cobalt that may be larger than any other in the country — and now also contains the nation’s only primary cobalt mine.

Roughly 40 miles long by about 10 miles across, the Idaho Cobalt Belt consists of rock that is more than 1 billion years old, Idaho State Geologist Claudio Berti told the Statesman.

Elements like cobalt are often collected as byproducts of mining for other substances, because the concentrations can otherwise be too low to be profitable. But a combination of the belt’s unusual makeup and favorable economic trends have brightened prospects for investors.

To wean an industrial economy off of fossil fuels, U.S. and world leaders point to electric vehicles as a necessity. President Joe Biden’s administration so far has poured billions of dollars into the transition, including a national network of charging stations, clean public transit and domestic access to critical resources.

But vehicles that don’t burn gasoline still require an array of materials that must be extracted from the Earth. Cobalt’s role in the green economy is driving the global market for the resource, which is expected to reach more than $19.4 billion by 2030, according to some estimates.

Along with nickel and lithium, cobalt is an important ingredient in the lithium-ion batteries used in electric vehicles. Cobalt provides stability to the complex amalgam that allows a battery to hold a charge over a long period, and helps prevent it from bursting into flames.

Including cobalt, most critical minerals used for batteries are mined in other countries.

“As we go away from a carbon-intensive economy, we will be moving into a mining-intensive (one),” Berti said in a phone interview. “Unfortunately, there’s no other solution” other than, perhaps, nuclear power, he said.

The work of Jervois’ miners near Salmon could supply about 10% of current U.S. cobalt demand, or what amounts to enough batteries to power about 400,000 electric vehicles per year. The mine also is likely to expand, Jervois CEO Bryce Crocker told the Statesman. While the operation has relatively small global implications, its status as the only U.S. mine set to primarily produce cobalt raises its stature and importance, he said.

“Cobalt really does matter for the United States,” Crocker said, noting that it has a critical function for an electric vehicle’s performance. “Essentially, without cobalt, the vehicle can’t have the requisite amount of nickel, so it can’t go fast and it can’t go far.”

By stabilizing a battery’s chemistry, cobalt allows manufacturers to add other materials that improve its performance. Technological advancements may one day reduce, or even eliminate, the need for the element in EV batteries, but officials have pointed out that could be some time off.

In the years to come, ore will be bored out of the mountain and churned through a sequence of mills until a fine sand is produced that can be shipped out of the country to a refinery. No cobalt refineries exist in the U.S., so Jervois’ product will likely be sent to one the company owns in São Paulo, Brazil. The mine could produce as much as 16,000 tons of cobalt before it’s done, at a value of hundreds of millions of dollars.

Some of the excitement over the mine stems from its expected benefit as an economic driver for the area. Republican officials celebrated its launch, lauding the project as a boon for the state at the mine’s opening ceremony in October.

“The economy, the schools, the community were built historically off of the backs of mineral wealth,” Gov. Brad Little told the Statesman.

But cobalt mining in Idaho also has a perilous history.

For decades, mining companies extracted cobalt and other minerals from the Blackbird Mine, to the detriment of local ecosystems. The old mine sits next to a creek on the way to Jervois’ new operation.

Both mines are a few miles south of the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness, home of the rugged Bighorn Crags and a gorge deeper than the Grand Canyon.

CAN END HERE

Conservationists recognize cobalt mining need

Despite memories of past industry missteps, some environmentalists have cautiously accepted the cobalt mine, since they view some critical mineral extraction as a necessary consequence of their value system.

Josh Johnson, the acting Central Idaho director of the Idaho Conservation League, told the Statesman that the group has a climate campaign focused on reducing greenhouse gas emissions statewide, part of which is expected to occur through electrifying the transportation sector. More than half of Idaho’s carbon emissions come from transportation, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Their organization realizes certain metals such as cobalt are needed for the clean energy transition, Johnson said. But mining often has been concentrated near indigenous people and other minority populations, which is a historical pattern that should not be repeated, he added. Nor should it be consigned to other countries.

“It is not appropriate for us living here in America to drive all our electric vehicles and just export the environmental harms of that elsewhere,” Johnson said, noting that he’d like to see mineral recycling increase with demand.

At the same time, the Conservation League plans to closely monitor the Jervois mine, ensuring company leadership meets their environmental requirements and stated goals. Johnson said he recognizes that extractive industries have jumped on efforts to transition to clean energy because they see an opportunity for profit.

“It’s important for all of us to remember that mining companies are just that — they’re mining companies,” Johnson said. “They are beholden to their shareholders. They are trying to maximize profits. They are not altruistically trying to solve the climate crisis.”

Jervois has partnered with the Idaho Conservation League to protect fish in the Upper Salmon River Basin. The company has committed $150,000 per year to the program for the life of the mine, which is now set at seven years but may be extended. Idaho Power also provides the mine’s electricity, half of which is renewable.

“We’re temporary custodians here,” Crocker, Jervois’ CEO, said of the mine near Salmon. “When you come back past here in 30 or 40 years, you won’t be able to tell that there was ever a mine here.”

Rather than an open-pit mine, the Jervois mine is accessed through tunnels into the mountain, which will be refilled and sealed off once mining is complete. The company plans to reforest the mine site and remove all of its buildings as well.

Hayes, the Conservation League’s executive director, told the Statesman at Jervois’ opening that he doesn’t believe there is such a thing as “sustainable mining,” because mined resources cannot be regenerated in human time spans. He does, however, think there can be “environmentally responsible mining.”

“We hear mining companies often say, ‘Don’t judge us by what was done 50 years ago, judge us by the proposal that’s in front of you now,’ ” Hayes said. “And so we take that to heart. … I think that there’s a lot riding on how this mine comes into production and how it operates. People are watching very closely.”

Bond values raise questions

The new cobalt mine, which Jervois officials said employs stringent environmental precautions, is endorsed by each of the state’s four federal lawmakers. Rep. Russ Fulcher, R-Idaho, who sits on the U.S. House Natural Resources Committee, is among them.

“Their quest to get permitted has existed long prior to me being in Congress,” Fulcher, starting his third two-year term in office, told the Statesman in an interview. “It’s my understanding they’ve got the best harvesting technology there is. It’s more (environmentally) friendly than other nations employ by far, and this is something that we have to have.”

Jervois’ plans include an on-site water treatment plant, which the company says will be used if water coming out of the mine site has elevated levels of heavy metals or other toxins.

The company also has posted reclamation bonds associated with the project, which are required by the government to ensure sufficient funds exist for cleanup after a mine closes — even if the company has gone bankrupt.

U.S. Forest Service documents, as well as interviews with a former local Forest Service employee and the mine’s manager, showed that the current reclamation bond amounts are lower than what initial estimates suggested cleanup could cost.

In 2009, the Forest Service estimated that reclamation bonds — including a mix of funds to recover surface disturbances and treat contaminated water — would cost $44 million, plus or minus 20%, according to agency documents reviewed by the Statesman.

Three years later, the estimated amount for long-term water treatment alone was about $42 million, according to Julie Hopkins, the retired minerals program manager for the Salmon-Challis National Forest. The Forest Service is supposed to periodically review and update proposed reclamation bonds, to assess how costs have changed.

Jervois’ combined bonds cost a total of about $40 million, Matt Lengerich, the mine’s executive general manager, told the Statesman.

Alicia Brown, a Jervois representative, added by email that reclamation bonds for the project were determined in accordance with Forest Service guidelines. In the decade since the 2009 estimate, “numerous changes in design and execution have been taken into account in updating the required bonding amount,” Brown said.

The apparent declining value of the bonds worries Hopkins.

“How can the bond be lower now than it was 13 years ago with inflation factored in?” she said in an email.

On Friday, Amy Baumer, a Forest Service spokesperson, told the Statesman by email that the bond amounts are still under review, account for inflation and have “not been finalized.”

Hopkins said she isn’t opposed to mining. A domestic source of cobalt is good, she said, especially if it benefits her community economically and doesn’t violate human rights. Child labor is widely reported at cobalt mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the world’s leading source of the element.

But Hopkins said she’s concerned that political pressure cheapened the reclamation bonds, and could limit the government’s ability to pay for necessary environmental cleanup.

“The Forest Service had a lot of pressure from Idaho congressionals or legislators to respond to Formation Capital’s needs, and I can only assume that trend continued when Jervois purchased the project,” Hopkins said.

Formation Capital is a subsidiary of eCobalt Solutions, a Canadian company that Jervois acquired in 2019 as part of its takeover of the mine.

Nine years before Jervois acquired the project, a nearby area of the Salmon-Challis Forest was designated as critical habitat for Columbia River bull trout. The new designation meant the mine’s environmental impacts on these areas would have to be reassessed.

But that assessment wasn’t completed until October, according to documents obtained by the Statesman through a public records request.

A letter from the Salmon-Challis’ District Ranger Bobbi Filbert to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in October noted that the forest had been notified of the need to reassess the area in 2018, and that the assessment “stalled” in 2020 as the mine’s ownership changed hands.

Baumer said that operations at the mine were mostly inactive during the 2010s, and that the Forest Service was notified by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service of the need to initiate further review in 2018.

The delays happened in part because of changes to personnel and mine ownership, she said.

“It seems that sometimes the can gets kicked down the road, and other times, decisions happen very quickly with less scrutiny,” Hopkins wrote. “I think operations for ANY mine should be based on application of law, regulation and policy rather than on political pressure.”

In her email, Baumer said the cobalt mine has gone through the same “rigorous process” as any Forest Service decision, and has taken into account public concerns and input from “interested parties.”

“We have used this process to … make a decision that sustains the health, diversity and productivity of the nation’s forests and grasslands to meet the needs of present and future generations,” she wrote.

Blackbird Mine poisoned fish

Years back, the open-pit Blackbird Mine was active enough to lead to the founding of Cobalt, a tiny mountain town where as many as 300 miners and their families once lived. Cobalt had a school, a gas station and a bowling alley, said Salmon Mayor Leo Marshall, who lived there when his father worked the mine in the 1950s.

The mining slowed down and the town soon shuttered, but not without leaving a harmful stain on the landscape.

Heavy metals and other poisons released from the rock during mining leached or were dumped into Blackbird Creek. An earthen dam also held back some 2 million tons of mine tailings, which are the waste products left over from the extraction process.

Those poisons destroyed steelhead and Chinook salmon runs in the Blackbird and Panther creeks, into which the former mine flows, Larry Jones, a mine specialist with the Idaho Department of Lands, told the Statesman in 1986.

“There are still chronic seepage problems around there from the mines, and now the streams are biological deserts,” he said at the time. “They are incapable of sustaining life.”

The state sued the Noranda Mining Co. over the issue in 1983, and the federal government followed suit in 1993. Noranda acquired the mine in 1977, Troy Saffle, a regional administrator at the Idaho Department of Environmental Quality, told the Statesman by email.

In the 1990s, Noranda and other involved companies began cleaning up the designated Environmental Protection Agency Superfund site, as required by the federal agency and the state. That included actions such as stabilizing waste rock, diverting clean water around the waste and operating a water treatment plant at the site, Saffle said. The requirements included $37 million in financial security for the project.

A tailings dam has been modified four times since 1994 to ensure its effectiveness, and is monitored, Saffle added. The mine site is now owned by a pair of multinational mining firms, Glencore and Rio Tinto.

These days, the affected creeks are “no longer impaired” by the historic contaminants, Saffle said. Alicia Brown, the Jervois representative, told the Statesman by email that the company is “committed to the responsible stewardship of the local environment.”

On a visit to the Jervois mine this fall, the road passed Blackbird Creek, where the water level was low and rocks along the creek bed shone a rusty orange color in the sun.

Salmon ‘cautiously optimistic’ about mine’s impact

On a night in early October, patrons crowded Bertram’s Salmon Valley Brewery in Salmon, the kitchen backed up with orders for burgers and salads.

The Main Street restaurant is one of only a few in town open after 8 p.m. But there was another reason for the Thursday night rush.

About 50 of the customers who packed into tables were connected to the new cobalt mine, suggesting the economic significance such an operation could have for a town of just over 3,000 people.

Restaurant owner David Craig manned the bar that night, as waitstaff tried to keep up with the swell of orders. A large group of firefighters also was at the restaurant, gathering one last time before dispersing for the year after a severe forest fire forced nearby residents to evacuate.

When miners damaged Blackbird Creek, locals felt its effects on the ecosystem.

Craig started hunting elk in Salmon about 20 years ago, when the arsenic and other heavy metals in the water left a dead zone at the creek’s edge.

“There was no vegetation for about 10 yards on each side of the waterline,” Craig said in an interview. An angler, too, Craig said locals weren’t supposed to cast in Panther Creek either, which Blackbird runs into.

By the time Craig began hunting in Salmon, cleanup of the Blackbird Mine had already begun, and he said he’s been impressed by the results. Every time he drives past Blackbird Creek near the mine site, he stops and gazes into the flowing water. Every time, he sees fish there, he said.

But even for a town that remembers the cobalt operation of years past, the new mine could rejuvenate its seasonal economy.

Since Jervois began constructing its mine, “anybody who does any kind of building trade in this town has been working for them,” Craig said.

Local stores have noticed the mine’s effects, too. Not all of them have been positive, they said.

Mark Brown, manager of Murdoch’s ranch supply store, said the mine has been good for business but caused him to lose employees.

“It’s kind of hurt the labor market,” Brown told the Statesman. “Because it’s hard to compete with mine wages.”

Jervois prides itself on being a part of the Salmon Valley, company representative Alicia Brown told the Statesman. She said Jervois’ wages must compete for mining workers across the West, not just locally.

When fully staffed, the mine is expected to employ between 160 and 180 workers, Lengerich, the mine’s executive GM, told the Statesman.

Elsewhere in town, local leaders are anxious to avoid becoming another boomtown.

Emery Penner, Salmon’s town administrator, said he hopes the community understands that the resources of the mine won’t last forever.

“Any benefit from it that comes a person’s way, be as responsible as you can with that benefit and make that benefit last, and don’t overextend your infrastructure,” Penner said. “Because it’s going to go away eventually.”

Though the mine’s economic benefit to Salmon will be largely based on the growing demand for electric vehicles, the town has few. There’s only one charging station, for Teslas, at the Stagecoach Inn, according to a national inventory.

In the small, isolated town, Craig said locals are used to looking after themselves and living off the land. Still, the seasonal economy of a river town can make it hard for businesses to turn a profit in the winter.

“But the miners — that’s a year-round thing,” Craig said. “I don’t think people here are at all opposed to the mine. They’re just cautiously optimistic.”

Little: EV shift ‘makes good economic sense’

The next day, Jervois company executives and federal and state officials turned out for the mine’s opening ceremony some months before the mill is expected to churn. That isn’t scheduled to happen until early next year, according to company officials.

On the hillside above the mine entrance, Jervois employees in matching neon green uniforms set up a large tent, a number of chairs and a podium to welcome Little, executives from Australia, the country’s U.S. ambassador and a top energy official with the Biden administration.

The weather was warm for the season, with clear skies that nearly equaled the jubilant mood of the gathered leaders, who either made the 2-hour drive to the mine site along 42 miles of dirt road or flew in by helicopter.

Jervois’ leaders touted the importance of cobalt for sustainability and national security reasons, as mine employees and contractors stood outside the tent and attentively watched.

Aside from electric vehicles, cobalt has other applications. By some estimates, the market value of cobalt is expected to more than double by the end of the decade, when a shortage of the critical element is anticipated.

About 70% of the world’s cobalt supply is produced in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where copper and cobalt mines reportedly host child labor and other human rights issues.

China, the world’s second-largest economy behind only the U.S., controls the majority of the cobalt market, with interests from the Asian nation owning or financing most of Congo’s largest industrial mines. As of last year, China refined 80% of the world’s cobalt, according to the U.S. Department of Energy, which U.S. leaders see as a national security threat.

Returning cobalt production to the U.S. has backers hoping to take a step toward catching up with China.

Each week in 2021, more electric cars were sold worldwide than in all of 2012, according to the International Energy Agency, an intergovernmental organization of which the U.S. is a member. About half of those sales were in China, but growth is happening across the globe, and the world’s largest car manufacturers have committed to making the transition.

Biden has set a goal of having half of U.S. car sales be electric by 2030, and scientists estimate that 90% of American cars must be electric by 2050 to meet widely accepted climate goals.

The adoption of electric vehicles will happen in “fits and starts,” Little told the Statesman, adding that scaling up of charging stations is a “huge problem” for the state. But, he said, a lot of the transition to EVs also “just makes good economic sense,” acknowledging his concern about climate change.

The federal infrastructure law passed last year provides millions of dollars to each state as part of the buildout of the nation’s EV charger network. Other federal legislation Biden signed this year incentivizes production of electric vehicles and their components, requiring each be assembled in North America and to include larger portions of battery materials sourced from the continent or from trading partners for consumers to receive a full $7,500 tax credit.

Jervois is reviewing other incentives passed during the Democratic administration that it can leverage, and already has applied to existing grant programs with the U.S. Departments of Energy and Defense, Lengerich said.

Idaho Republicans seek to counter China

For U.S. Sen. Jim Risch, R-Idaho, digging out critical minerals like cobalt from the state’s mountains is about establishing a reliable domestic supply chain to strengthen U.S. national security. The top Republican on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee aims to ward off future diplomatic entanglements with disfavored foreign trade partners — chiefly China — that have begun to corner the market.

The COVID-19 pandemic only underscored the sourcing issues already known to be a problem with these scarce elements, he said. The U.S. has the opportunity to gain back ground in this mineral arms race to maintain its standing as the world’s leading economy and global influencer.

“China’s the issue in national security and in foreign relations for the rest of the century,” Risch told the Statesman in an interview. “They are a near-term competitor for us now, economically, militarily and culturally … and they have a lock on a lot of the critical minerals that are needed around the world. The concern always is that you have to treat them with kid gloves when you’re dealing with them, because they can just cut you off.”

While state leaders largely sidestepped the climate issue, cobalt’s economic significance lends itself to rare bipartisanship in Washington, D.C. And Idaho, with its rich history in mining, is well positioned to benefit economically along the way because of the state’s wealth of the sought-after elements buried within its boundaries.

Risch, who also briefly served as Idaho’s governor, now hopes to leverage the spotlight on cobalt to inspire a new wave of mineral extraction in the state. He plans to introduce a pair of bills early next year — one focused on accelerating permits to increase domestic production, and another centered around encouraging more collaboration with ally nations to develop greater stability of the supply chain.

“This obviously has piqued our interest, the fact that we’ve got a player here in Idaho that wants to move forward on it,” Risch said of the Jervois mine. “And look, if it’s good for cobalt, it’s good for a lot of other stuff, too, that we badly need.”

He’s backed in the effort by the rest of Idaho’s Republican delegates, including Sen. Mike Crapo, as well as Reps. Fulcher and Mike Simpson.

“It’s a huge issue, and I’m tickled to see the cobalt mine finally open,” Simpson told the Statesman by phone last month. “There are others in Idaho — other minerals that are important, including antimony and rare earths — that are critical in this, whether it’s in our energy area or whether it’s in the defense area, or manufacturing.”

A retired state elected leader, former Idaho Gov. Butch Otter, has gotten involved, too. A month after leaving office in January 2019 following three terms, Otter joined the board of Electra Battery Materials, which was formerly known as First Cobalt Corp. The Canadian company owns mining claims not far from the Jervois operation, and, along with Codaho LLC/Koba Resources, is one of two other mining firms looking to jump into the Idaho market.

In summer 2019, Otter sent a letter to then-U.S. Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin, asking him to investigate potential Chinese involvement in Jervois’ move to acquire the mine. The Treasury secretary acts as chair of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S.

“I would urge you to review this transaction to ensure that Jervois — and the cobalt resources it is acquiring — is free from Chinese control,” Otter wrote.

That same year, Crocker, Jervois’ CEO, told The Australian Financial Review that the company has no Chinese ownership and aims to produce a cobalt supply chain for the U.S.

“Essentially you are getting sour grapes from a rejected dance partner,” Crocker told the Australian outlet at the time.

Jervois has “no substantial Chinese shareholders” and is “committed to securing Western supply chains,” company representative Alicia Brown reiterated in an email. “Jervois has no plans to sell any of the cobalt produced in Idaho to Chinese refineries.”

Otter did not respond to requests for comment from the Statesman. Reached by phone, Joe Racanelli, Electra’s vice president of investor relations, declined to comment about Otter’s previous allegations against Jervois.

The Treasury Department did not return email requests seeking clarification about whether Mnuchin or the U.S. Foreign Investment Committee investigated Otter’s claims.

But last week, Electra announced its purchase of more claims near its possible future mine site within the Idaho Cobalt Belt, which it promoted as the “largest unmined cobalt resource in the U.S.” The acquisition brings its total land rights in the area with known cobalt, copper and gold deposits to about 12.5 square miles.

Potential cobalt production at Electra’s mine site remains several years down the line, Racanelli told the Statesman. But the company’s continued investment shows the increasing push among competitors to break into the Idaho market based on the nation’s renewed desire for critical minerals, thrusting the state onto the global stage.

As more mining projects advance in the Cobalt Belt, environmentalists refuse to abandon their mission.

“Our solution to the climate crisis should not be mining our way to clean energy, because that just creates so many other issues in the long term,” said Johnson, the Idaho Conservation League’s Central Idaho director. “Mining is the biggest toxic polluter of water in the Western U.S. historically, and to this day, so we need to balance those things in an appropriate way.”