‘Living document’ gets a makeover

Idaho Constitution, after being repaired, cleaned at the University of Utah, was welcomed back to Boise this week

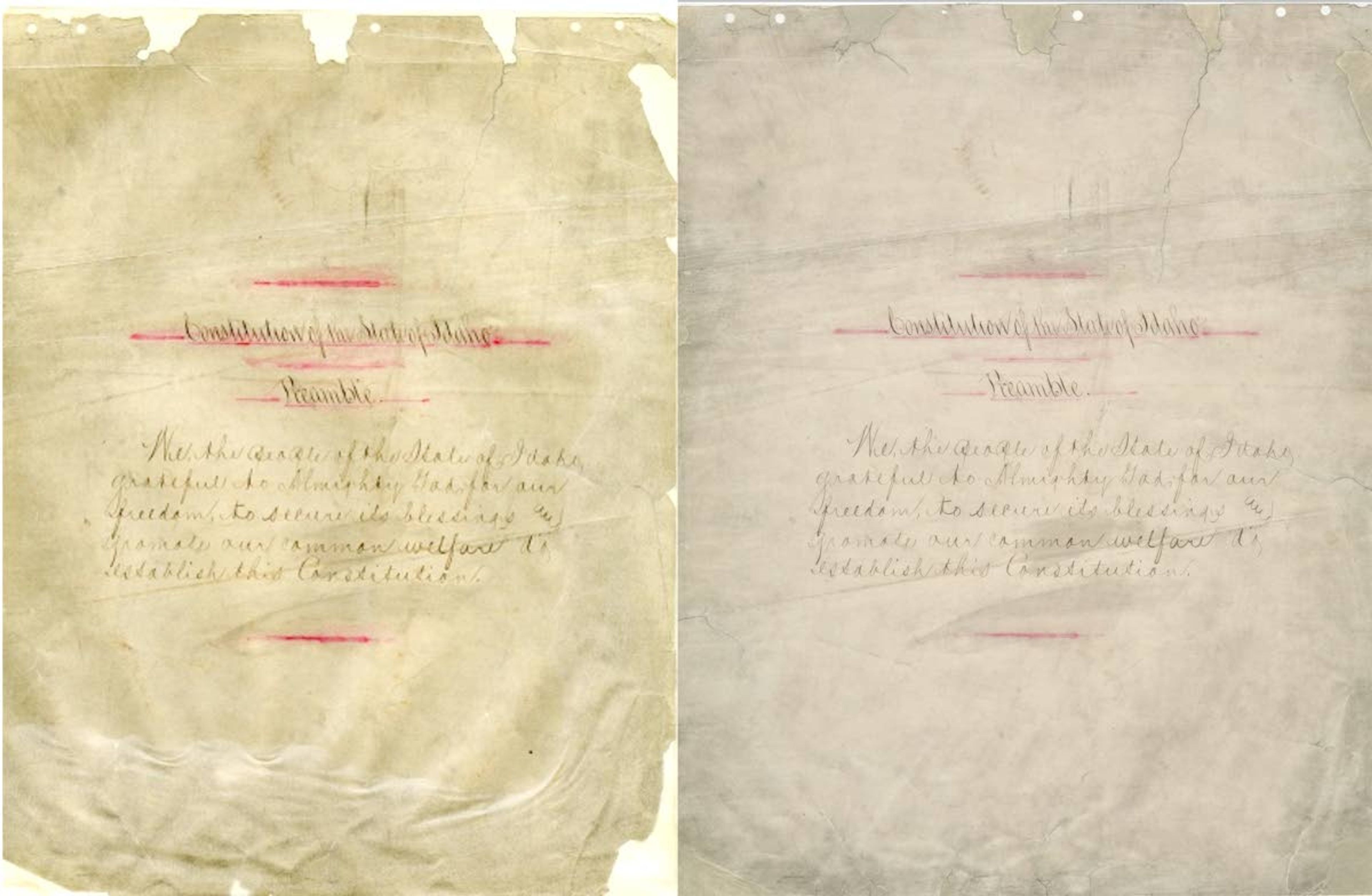

At 130 years old, the Idaho Constitution was showing its age.

Its binding was broken, its pages dirty and dog-eared. Some were torn, a few even loose. In 2018, the Idaho State Historical Society decided the constitution needed some serious TLC.

The Foundation for Idaho History raised $25,000 to have the constitution undergo a thorough repair and cleaning at the University of Utah.

Today, the constitution is repaired and rebound, with a handsome goatskin cover. Gov. Brad Little welcomed the constitution back to Idaho this week. The document that sparked Idaho statehood, created its government and guaranteed Idahoans their rights goes on public display beginning March 10 at the Idaho State Archives in Boise.

Now that it’s cleaned and restored, it’s easy to see that the Idaho Constitution is not a stack of paper gathering dust on a shelf.

“It is a living document and it has serious relevance to what we do,” Magistrate Judge Michael Oths told Idaho Public Television. “It’s the framework for all of our laws. The framers were mostly lawyers and were pretty smart people, but they couldn’t have anticipated everything that could come down. ... But, yes, it’s absolutely relevant.”

In October, Brad and Teresa Little and Historical Society officials flew the constitution to Utah, where Gov. Gary Herbert formally greeted the delegation and the document. As far as anyone knows, that was the first and only time the Idaho Constitution had ever left Boise, let alone traveled out of state.

“You step back ... and you say, ‘My goodness, this is truly an historic moment,’ ” Teresa Little said.

In fact, Collections Archivist Layce Johnson had to consult with state lawyers: Was it legal to take the document out of Idaho? Did the document need to be insured? And how do you transport a treasure that is irreplaceable?

“Along the way, there were many decisions we had to make,” Johnson told IDPTV for its documentary, “Idaho’s Constitution Revealed.”

The Idaho Experience episode premieres March 8. It follows the four-month Utah restoration work, the conservators who performed the repairs and the Idaho staff care for the constitution. The documentary also traces the history of the constitution from its drafting in 1889 to the teachers, lawyers and lawmakers who study it, interpret it and even try to amend it today. This 130-year-old drama has a rich cast, including villains, heroes and overlooked characters whose roles have been untold or unappreciated.

“This project has revealed so much more than I ever thought it would when we first started,” Johnson said.

Two governors, two consititutions

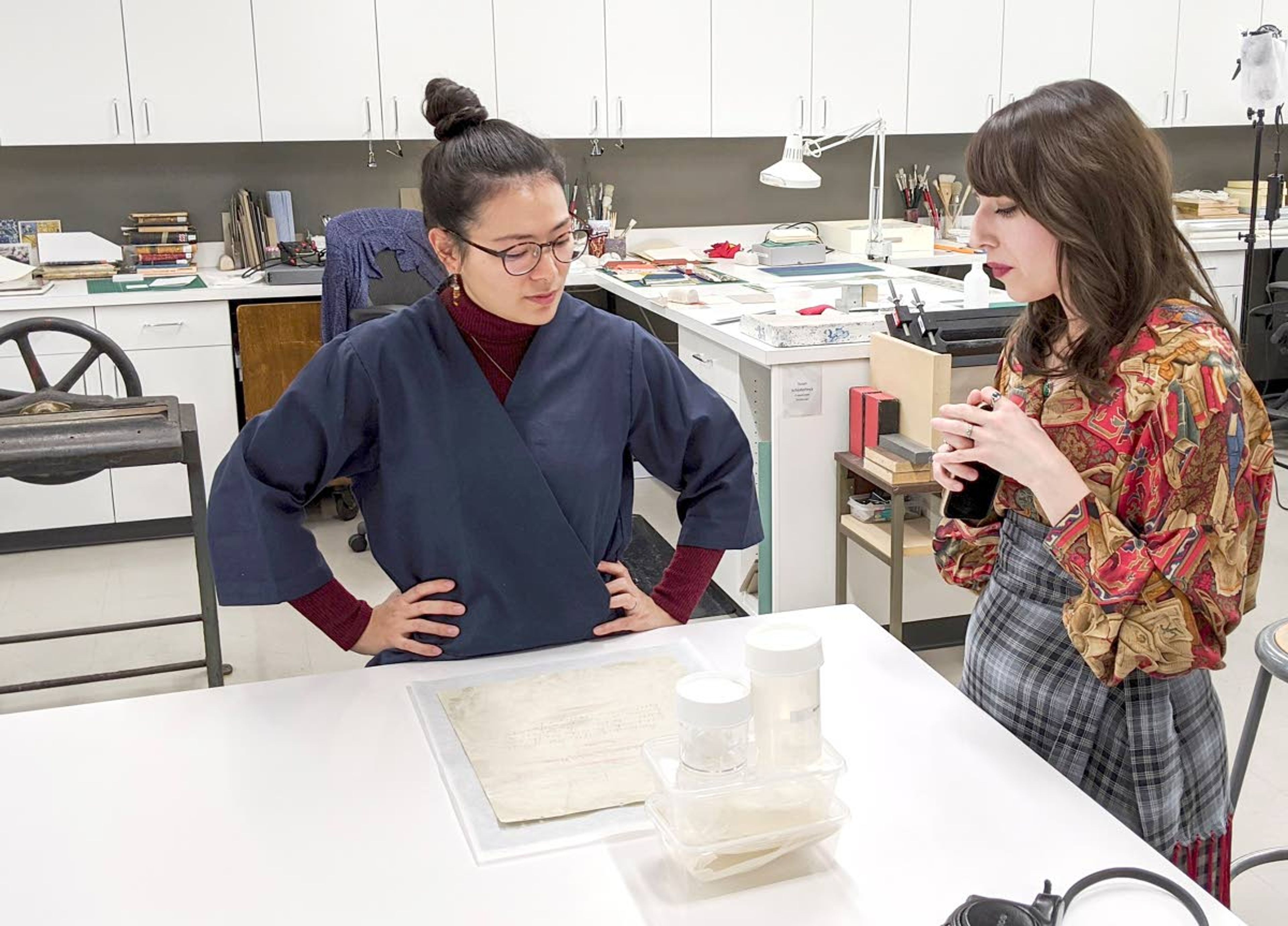

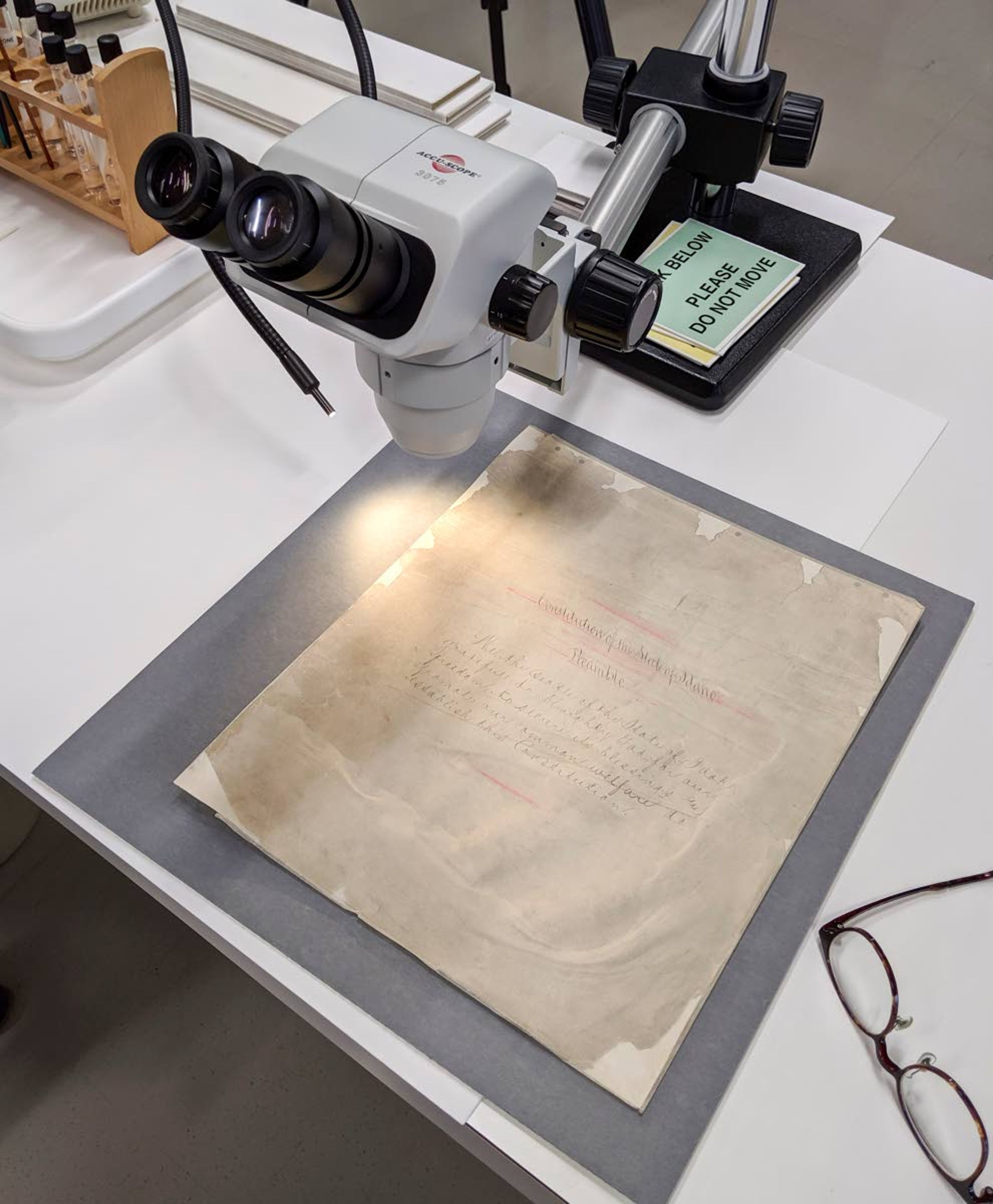

The preservation lab at the University of Utah’s Marriott Library is among the leading conservation facilities in the West, Johnson said. Idaho has nothing comparable, so taking the document to Utah was the obvious choice.

The Utah lab also has done conservation work on the Utah Constitution, said Randy Silverman, head of preservation at the Marriott Library. In fact, when the Idaho Constitution arrived, both state constitutions and both state governors were all together in Silverman’s lab. The warm welcome in Salt Lake City was especially noteworthy to those familiar with the Idaho Constitution’s harsh 1889 provisions that banned members of the LDS church from voting or holding public office.

The Utah conservation team also is creating a replica edition of the Idaho Constitution that will visit Idaho libraries and schools, allowing the 19th-century original to remain in climate-controlled safety.

“Preserving that document is very important, the most important,” Little said. But a traveling copy “makes that connection way better than having it locked up in the archives here in Boise.”

Traveling through time

Archivists and conservators are a unique breed. They view themselves as participating in a kind of time travel: Documents and artifacts travel through time to reach them. It’s their job to get those items ready to be sent into the future.

“None of us own any of this stuff,” Silverman said. “We guard it. We show it to people in our tenure, and pass it along to the next generation.”

“Two hundred years from now, someone’s going to pick something up that I did and use it and value it,” said Arizona restorer Mark Andersson, who worked on the binding and cover. “It means a lot. My life has been based on the premise that that’s more important to me than making a lot of money.”

“My big dream with this project was to expose who archivists are and what we do,” Johnson said. “That archivists play a role in protecting the state’s history ... because we’re able to house these government records that hold our government accountable.”

Beyond safekeeping official records, archivists collect and protect business and nonprofit records, family papers, diaries, photos and more. Said Johnson: “We’re really collecting the state’s history in its entirety.”

Got a photo from 1889?

Everyday people play an important role in helping history’s caretakers. The archives’ photo collection, for example, consists almost entirely of donated pictures. One big gap in the collection: No photos from Idaho’s 1889 constitutional convention are known to exist.

“So if there is a photo out there that lives in someone’s house, in their attics or their basement ... I would love to see it,” Photo Archivist Danielle Grundel said. “If you are a relative or a descendant of one of these individuals from the constitutional convention, we would love if you check your materials and see what you have there. They may have a treasure and may not even be aware of it.”

The biggest challenge for the conservators working on the Idaho Constitution was removing lamination from the first two pages, which required submerging the paper in a series of acetone baths. Otherwise, repairing the constitution involved simple, time-tested materials. The pages were patched using Japanese paper and wheat starch paste. The binding was sewn by hand with linen thread. The cover is strong, thin Nigerian goat leather.

Likewise, the techniques the conservators used on the constitution are as old as books themselves.

“Really, a book is four pages folded in half and sewn on the fold,” Andersson said. “That’s what books have been for 1,600, 1,700 years. ... Not that I hate Kindles, but it’s like books are intuitive and they’re long-lasting and they’re simple to use. They’re amazing things. And fundamentally, it’s the same thing that the Coptic Christians did in the fourth century.”

Bill Manny is a producer and writer for Idaho Public Television. He can be contacted at bill.manny@idahoptv.org.