Native crisis line marks a year’s existence

The first lifeline of its kind in nation, Washington state service has tallied more than 4,000 calls in its first year

A year after its launch, Washington’s Native and Strong crisis lifeline has answered more than 4,280 calls by Native residents.

The lifeline for and by Native American and Alaska Native people is the first of its kind in the nation, and is integrated into the state’s 988 suicide and crisis lifeline.

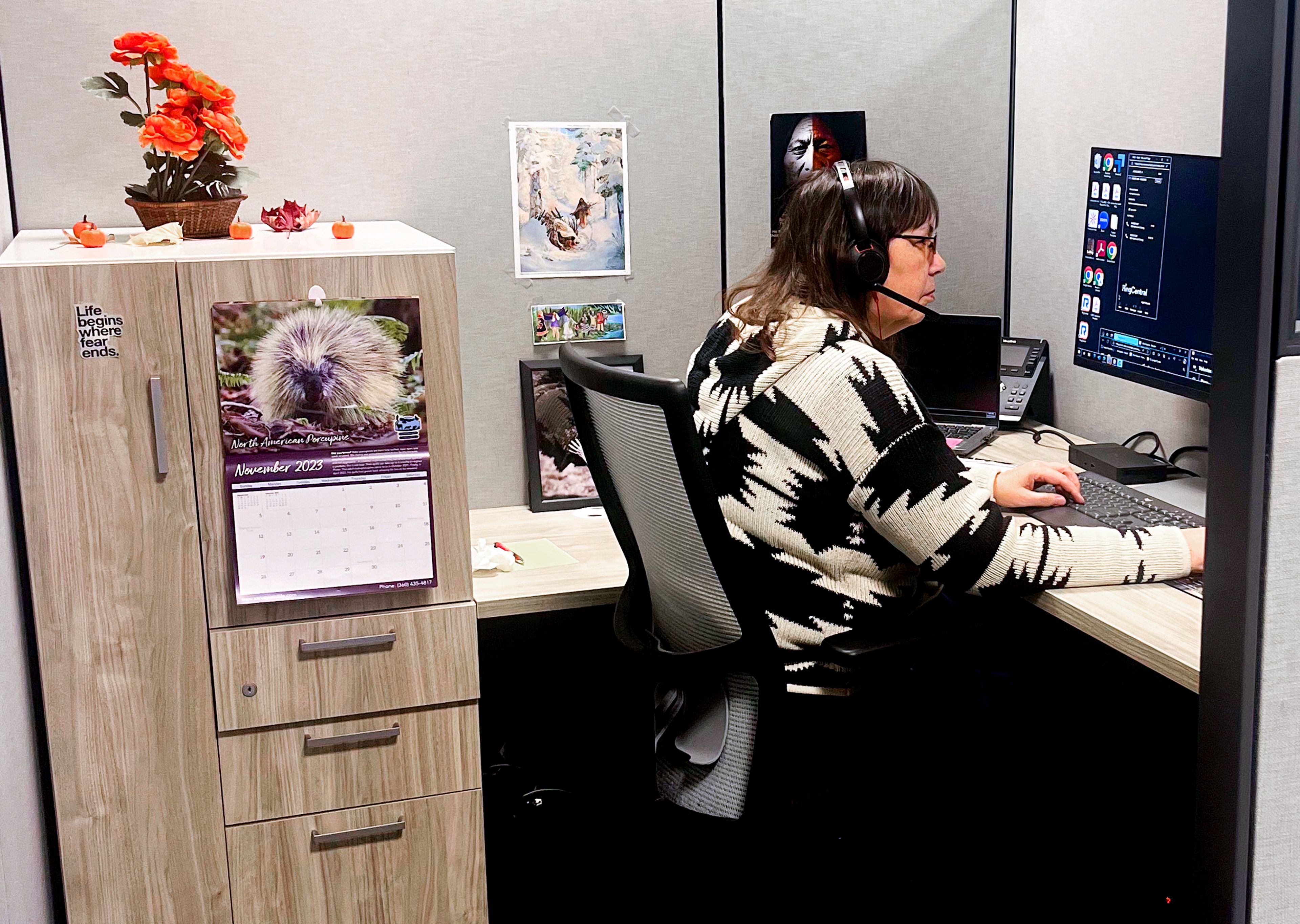

Mariah Thompson is a tribal crisis counselor and Coeur d’Alene Tribal Member. She’s also a descendant of Native Spokane and Kalispel people.

Many Native people, Thompson said, have had similar traumatic experiences, and are often affected in some way by issues like chemical dependence or domestic violence. Being able to relate to callers in that way makes it easier to communicate and connect, she said.

“When we have other Natives that are willing to share what they’ve been through, it empowers all of us that have been through the same thing,” she said.

Valarie Moon is a tribal crisis counselor and enrolled member of the Te-Moak Tribe of Western Shoshone in the Elko Band. She has personally been affected by suicide, Moon said, as have all the Native people she knows.

“It happens so often in Indian country,” she said. “Every Native is affected by suicide.”

Native people are disproportionately affected by suicide, with suicide being the second-leading cause of death for American Indian and Alaska Natives between the ages of 10 and 34 as of 2019.

Talking to someone who understands that experience is powerful, Moon said.

“We all have such great conversations with everybody (who calls), because we get it,” she said. “We’ve been through that so many times in our lives.”

The lifeline isn’t just for people at risk of suicide, said Robert Coberly, tribal resource specialist with the Native Resource Hub. Coberly, a Tulalip tribal member, said many callers are looking for cultural connection.

“We’ve been shamed and blamed for who we are, and what we’ve been through,” he said. “A lot of us, we’re in different cities and different tribes, or different reservations. I just want to connect people to resources, get them where they want to be.”

One caller, Thompson said, was struggling with mental health and felt unfulfilled in their job. Thompson was able to connect the caller to the Native Resource Hub, which helped them find a job that fit better.

“It’s not just suicide,” Thompson said. “If we feel that there’s something more that we could assist them with, we’re doing that.”

Sometimes, crisis counselors will get return callers updating them about their lives or thanking them for their help.

“When I first started, I got a call from at least three elders, and they passed the phone around just to tell me thank you for doing the work I do,” she said. “That whole call made my first six months on the job, because it feels so rewarding.”

Before she started working at the lifeline, Thompson said, she had been trying to do similar work on her own, wherever she could, to help other Native people.

Because crisis counselors receive certifications through the Department of Health, Thompson said, she’s been able to pursue a career she thought would be out of reach for her.

“I thought that I had to go to college in order to do this type of work. And eventually, that’s the goal,” she said. “But with the life that I had, college wasn’t really an option for me.... So I’m so thankful that I’m able to do that.”

Moon had always wanted to be a counselor, she said, and previously worked for different tribes and nonprofits before the lifeline. The training she received removed one of the barriers she faced to do work that matters to her.

“That’s how I think we’re indigenizing and decolonizing mental health,” she said.

Another part of decolonizing mental health, Moon said, is being able to talk to callers about spirituality and taking care of themselves through Indigenous practices.

Moon recalled lessons from her uncle, and said what she learned from him about spirituality helps inform the calls she takes.

“You can come back to your prayer, come back to your creator, come back to your spirituality, your culture,” she said. “I think that’s what we’re all subconsciously seeking is that connection to the ultimate divine, and I think that ultimate divine is our spirituality, our connection to whatever is before us and whatever is after.”

Coberly said for him, decolonizing mental health is about taking pride in who he is, and showing others it’s OK to seek help.

“I do therapy every week, once a week,” he said. “(I) just take pride in it, and just tell people what’s working for me and what I do. And then hopefully other people find their way through whatever journey that is.”

Since its launch, lifeline staffing increased from 11 to 23 crisis counselors, with hopes to hire more in the coming year, said Tribal Services Program Manager Amanda WhiteCrane.

Native and Strong Lifeline is limited to phone calls, she said, but there are plans to work on expanding to chat and text in the coming year.

Sun may be contacted at rsun@lmtribune.com or on Twitter at @Rachel_M_Sun. This report is made in partnership with Northwest Public Broadcasting, the Lewiston Tribune and the Moscow-Pullman Daily News.