Nearby History: History of Appaloosas in the Northwest

Commentary

In February 1806, Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery was pinned down at Fort Clatsop in present day western Oregon at the mouth of the Columbia River.

Daylight hours were short, food was scarce and the men were eagerly awaiting the spring weather that would allow them to begin their return trip east.

Meriwether Lewis used this down time to journal extensively about his observations and perceptions of America’s newly acquired western lands.

In one such journal entry, Lewis commented on the numerous horses the corps had encountered in the plains extending west from the Rocky Mountains, some of which were “pided (pied) with large spots of white irregularly scattered and intermixed with the black brown bey or some other dark colour.”

“Their horses appear to be of an excellent race; they are lofty elegantly formed active and durable,” wrote Lewis. “In short many of them look like the fine English coarsers and would make a figure in any country.” Given Lewis’ Virginian heritage and status as an experienced horseman, his comments are particularly striking.

According to Lewis, a number of Columbia Plateau tribes, including the Nez Perce, possessed horse herds of significant size.

The history of the Appaloosa, a breed now synonymous with both the Nez Perce and the Palouse, begins long before Lewis and Clark’s time.

Spotted horses, with their distinctive color markings, appear in French cave paintings from the Upper Paleolithic Period, Egyptian tombs from 1400 B.C., and seventh century Chinese artwork.

When the Spanish arrived on the shores of Mexico in the early 1500s, they brought with them a great number of horses from the Andalusia region, a stock that commonly sported spots.

As the Spanish pushed north into present-day America, so too did the horse.

Despite concerted Spanish efforts to prevent native peoples from acquiring the animal, by the late-18th century, many American Indian tribes along the western side of the Rockies had incorporated horses into their way of life.

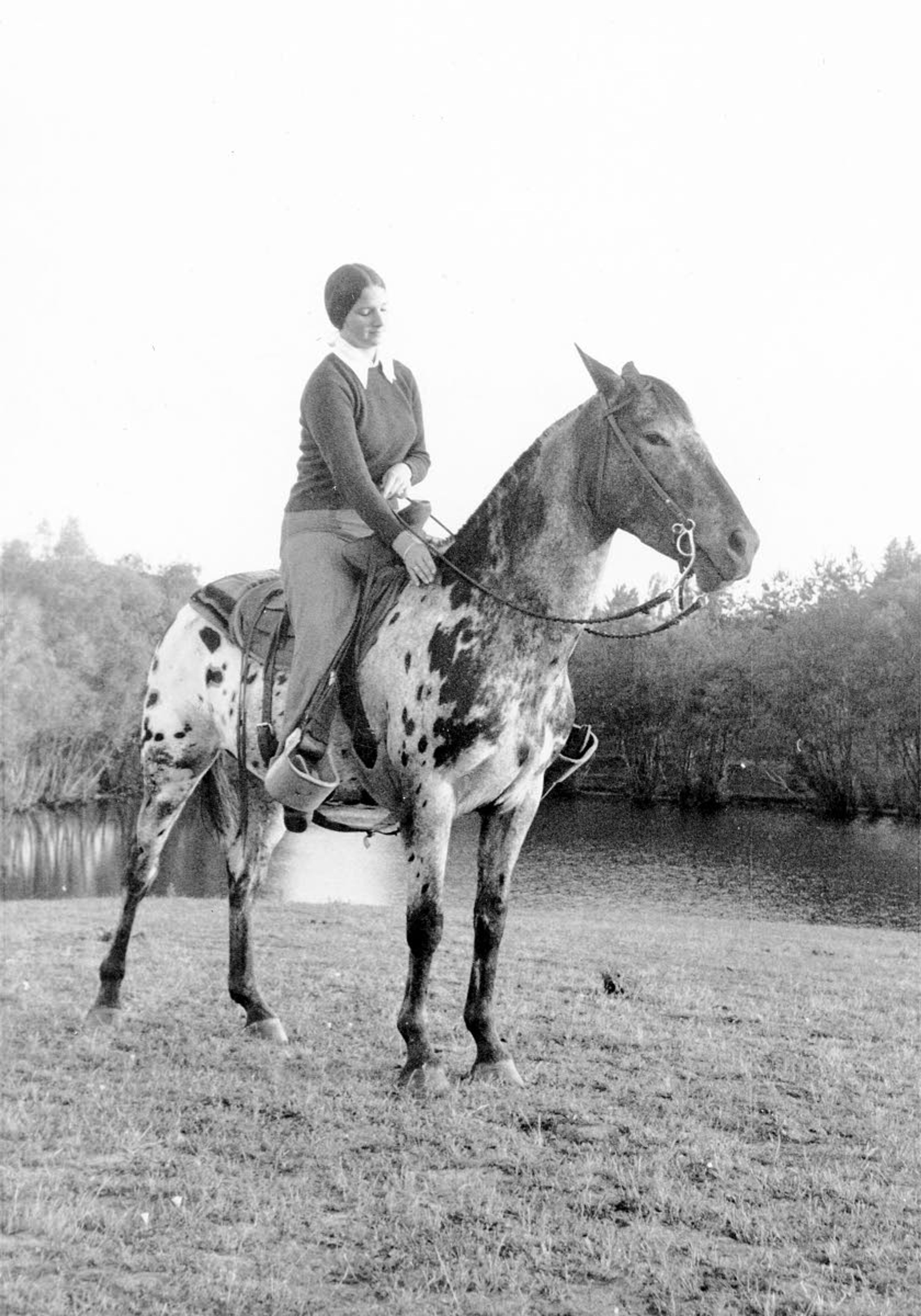

The Nez Perce, or Nimiipuu, became particularly adept at raising and handling horses. Through selective breeding, the Nimiipuu developed larger herds of beautifully colored and remarkably athletic animals. Spotted horses were particularly prized because of their attractive markings, which resembled war paint and thus they were always ready for battle.

While encounters with the Nimiipuu were remembered as peaceful by members of the Corps of Discovery, the next wave of American arrivals brought with them irrevocable changes.

Missionaries like the Spaldings discouraged horse ownership in the American Indian communities in which they settled. Horses encouraged conflict, missionaries believed. Moreover, horse racing was a popular sport among the Nimiipuu and the Spaldings would not stand for gambling among their converts.

Following the discovery of gold in the region, the Nimiipuu were forced onto reservations, greatly reducing their grazing territory. Those who did not sign the reservation treaty were pursued by the U.S. Army through parts of Idaho and Montana throughout the summer of 1877, taking with them large number of Appaloosa. When Chief Joseph surrendered just south of the Canadian border, he turned over nearly 1,100 horses.

During the last decades of the 19th century and the first of the 20th, the Appaloosa breed was nearly lost. Settlers on the Palouse preferred draft horses, and so they rounded up any animals left behind by the Nimiipuu and sold them to buyers in other areas of the country. Appaloosas became a rarity in the region, with a handful of ranchers maintaining the breed for their attractive look and ability around stock.

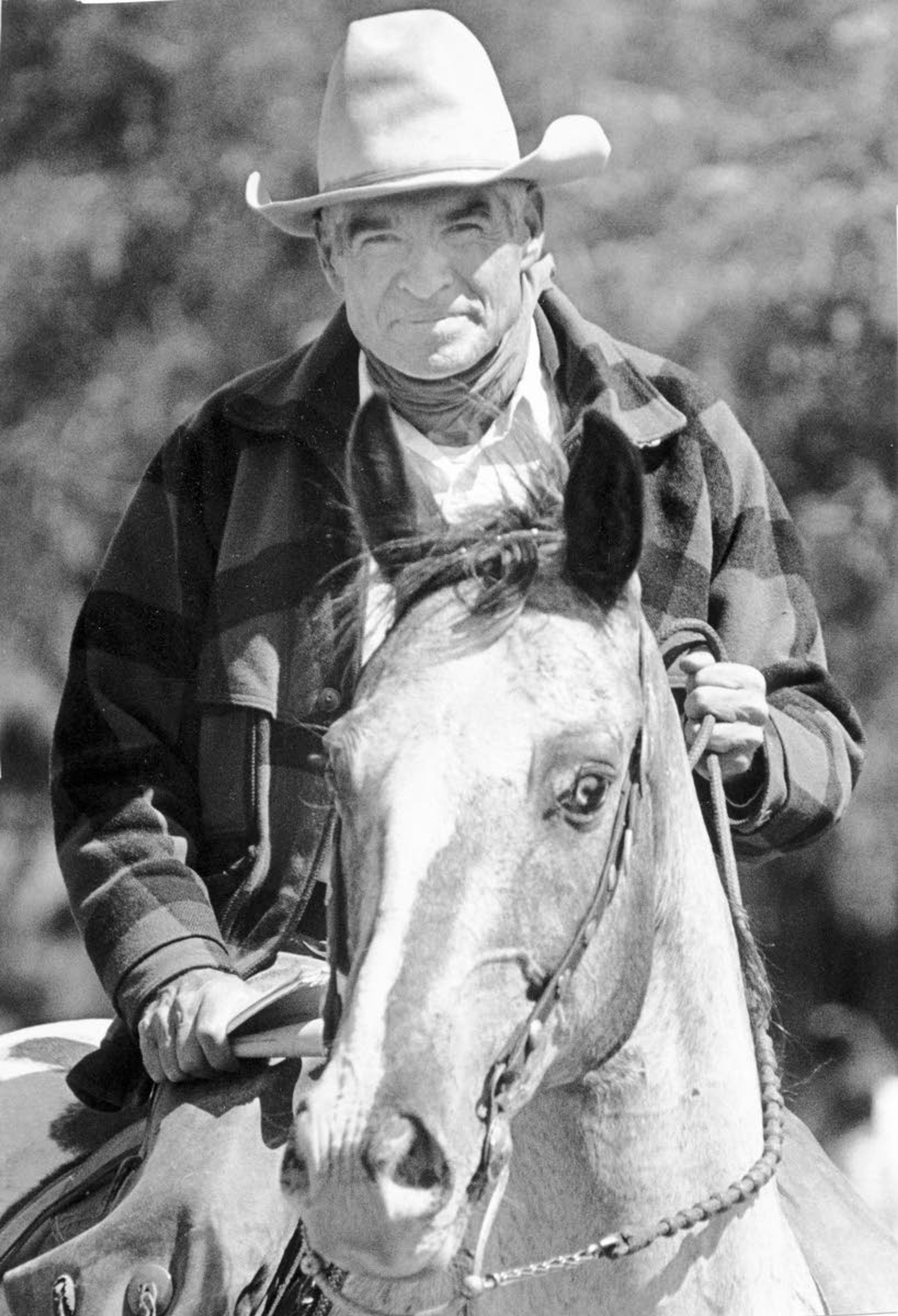

The breed’s fate changed around 1940 when a young Moscow man named George Hatley bought a good-looking Appaloosa stallion from a breeder near Colfax. Family stories of the “Appaloosy” that used to roam the Palouse sparked in George a curiosity, which ultimately led to the basement of his home becoming the Appaloosa Horse Club’s world headquarters.

If this very brief historical overview has whetted your appetite to learn more about Appaloosas, the Nimiipuu or the Hatley family, you should join us for the progressive dinner, “Meet Us at the Museums” on Feb. 2. Guests will visit the Appaloosa Museum for appetizers and a champagne toast before sitting down to a three-course dinner at the McConnell Mansion historic house museum. Tickets are limited and reservations must be made by Friday. Please visit www.latahcountyhistoricalsociety.org for more details.

Dulce Kersting-Lark is the executive director of the Latah County Historical Society.