‘Phoenix or bust’: the arc of University of Idaho’s saga

As a plan to rework the purchase flamed out, frustrations flared

By late February, the State Board of Education was losing the University of Phoenix narrative, and losing support in the Statehouse.

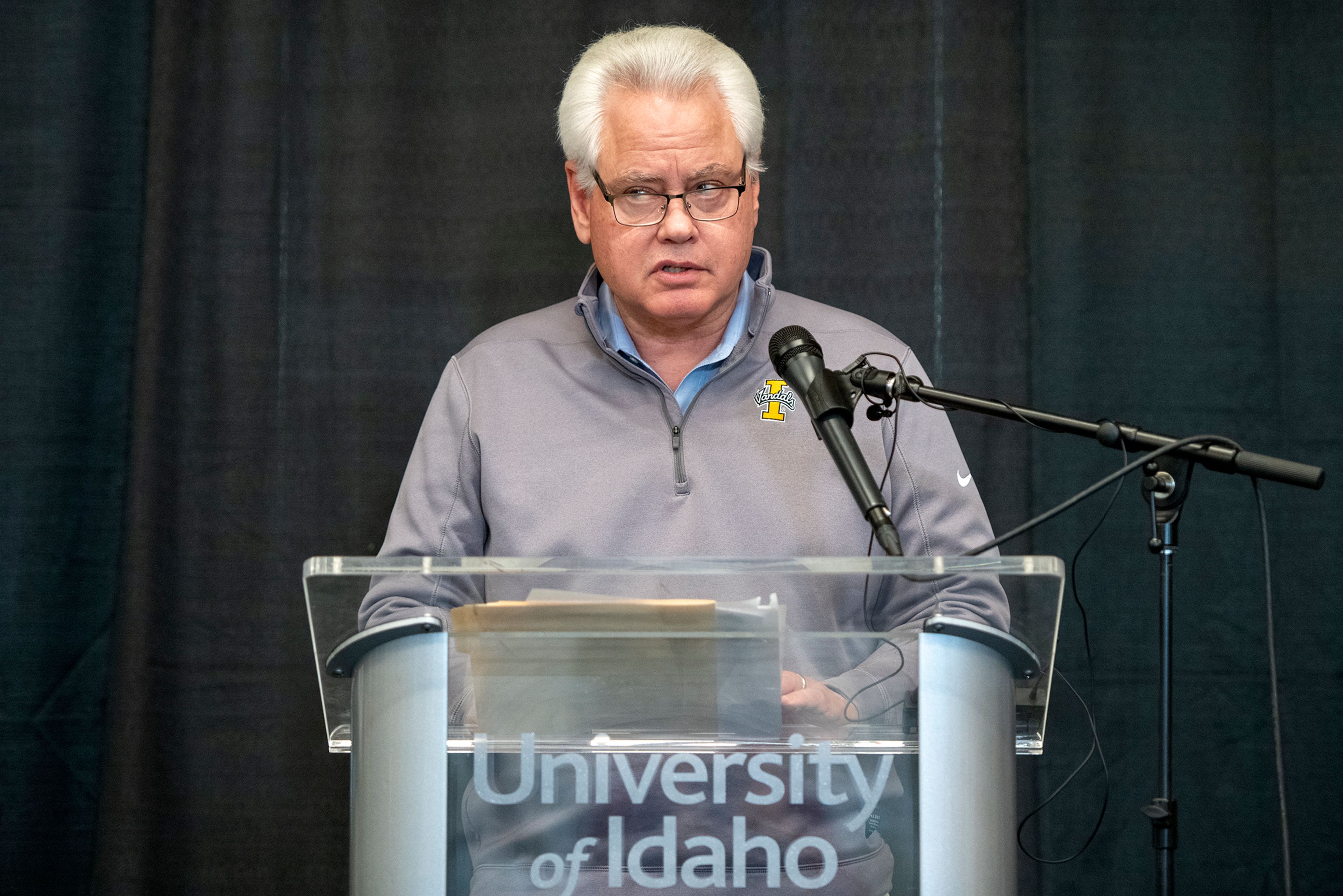

Executive Director Matt Freeman put his dismay in writing.

“Ever since (Attorney General Raúl Labrador) filed his lawsuit last June, the Board has necessarily kept a low profile on the merits and process of the transaction,” Freeman wrote in a Feb. 25 memo to board members.

“However, I do not believe we can maintain that posture any longer. Certain legislators and members of the media are vilifying the Board and impugning its motives and reputation. We need to get the facts around process, due diligence and the structure and benefits of the transaction out to policymakers and the public.”

But after Freeman’s memo, and by the end of March, both the House and Senate cast votes against the $685 million Phoenix purchase — throwing the University of Idaho acquisition into limbo, and delivering a sharp rebuke to the board that endorsed the plan in May 2023.

On top of that, the 2024 Legislature shoehorned language into a far-reaching school facilities bill that gives the Senate the power to confirm or reject a State Board executive director. (This new policy will go into practice in 2025; Freeman is stepping down effective June 30.)

Through a public records records request, Idaho Education News obtained hundreds of pages of State Board emails from Jan. 1 through May.

The emails weave a story of the State Board’s failed attempts to head off a public embarrassment at the Statehouse. They also reveal strained moments between the players on the same side of the Phoenix debate — parties who maintain Phoenix could transform adult learning in rural Idaho, and provide the state with millions of dollars in revenue from the online education giant.

January-February: a courtroom victory, a gathering storm

For the board’s eight members — seven gubernatorial appointees and elected state superintendent Debbie Critchfield — a courtroom battle overshadowed the advent of the 2024 session.

In January, Labrador’s lawsuit came before Ada County District Judge Jason Scott.

The judge sided with the board, saying its closed-door discussions of the Phoenix purchase were allowed under Idaho open meeting law. But the Jan. 30 ruling only came after all eight State Board members took the stand for hours of laborious and sometimes repetitive questioning.

When the testimony wrapped up on Jan. 25, Freeman gave board members a pep talk.

“It has been a frustrating and stressful distraction from the education advocacy and leadership work you were appointed to do,” he wrote in an email. “You may be feeling a bit disillusioned or demoralized with public service. Quite honestly, and unfortunately, I wouldn’t blame you if you were.”

Board members had little time to celebrate Scott’s verdict. By early February, a Statehouse game of peek-a-boo began to play out.

On two occasions, a proposal addressing the Phoenix issue appeared on a Senate committee agenda — but was pulled off the calendar at the last minute. This bill was never introduced, but it caught the attention of Phoenix backers.

“Lots of risks starting to escalate and wanted to make sure we get on the same page,” said Theo Kwon, chief operating officer of Apollo Global Management, Phoenix’s owner, in a Feb. 3 email to State Board member Kurt Liebich.

Early that Saturday evening, Liebich wrote back. “It looks like the Legislature is going to try to create more mischief.… I have not heard any details about what they are going to discuss, but I will plan on attending the meeting.”

That Senate committee meeting never materialized. But other meetings, and tense conversations with lawmakers, would soon follow.

February-March: The debate shifts to the House

The first Phoenix proposal went public on Feb. 15. The House State Affairs Committee introduced a resolution that would require the State Board to reconsider its Phoenix vote, while giving the Legislature the authority to sue to stop the sale.

Joined by Caroline Nilsson Troy — a former legislator who now serves as UI’s government relations liaison — Freeman went to committee members to cajole and commiserate.

“We opened each meeting telling them we understand they are frustrated, and we (Board and U of I) are frustrated too because the transaction has not progressed as intended,” Freeman said in his Feb. 25 email to board members. Freeman laid some of the frustrations at Labrador’s office door, saying the open meetings lawsuit prevented the State Board and UI from fully discussing the sale with lawmakers.

House State Affairs’ chairperson remembers his meeting differently.

Rep. Brent Crane said he didn’t ask questions. Instead, he said he was pressed for information — namely, a sneak preview of what he planned to ask in a public hearing. Crane told the group to come to the committee room and find out.

“The conversation needed to take place in a public setting, but it was also strategic,” Crane, R-Nampa, told EdNews on Thursday.

Freeman said he and Troy heard a chorus of concerns. Lawmakers said they needed more financial details. They said they had heard only problems with the purchase — nothing about the positives. And they wondered when and how they would have a say in the decision.

All of these concerns flavored the Statehouse’s Phoenix debates, which began in House State Affairs.

The fate of the House resolution was likely sealed before Freeman and Troy tried to win over committee members.

The resolution had backing from Crane, the committee’s powerful chairperson, who had already publicly admonished the State Board and UI for cutting lawmakers out of the conversation. The resolution had bipartisan backing: Rep. John Gannon, D-Boise, was its co-sponsor.

Behind the scenes, and in emails obtained by EdNews, Crane and two other House State Affairs members restated their concerns with the deal.

In a Feb. 29 email to Crane, Rep. Heather Scott criticized UI President C. Scott Green’s decision to hire his previous employer for Phoenix consulting.

“Tremendous conflict of interest,” said Scott, R-Blanchard.

As EdNews reported on Feb. 27, the international law firm Hogan Lovells had received $7.3 million in fees for Phoenix-related due diligence work; Green had worked for the firm before returning to his alma mater as president in 2019.

In emails to a constituent — and to Joanna Hayes, editor of the Argonaut, UI’s student paper — Gannon restated his concerns. He said he had decided to keep silent on the purchase, until it became clear to him that important details weren’t being made public.

“Bigger is not necessarily better — The College of Idaho is a good example — and I am concerned about adding 80,000 out-of-state online students,” Gannon wrote Feb. 26.

On March 1, House State Affairs passed the resolution, with one no vote. On March 5, it easily passed the House, on a 49-21 vote.

February-March: Fitful, fruitless attempts to change the narrative

As an anti-Phoenix surge swelled in the Statehouse, the State Board tried to fight the tide. To no avail.

In early March, the State Board drafted a guest opinion, signed by Liebich, explaining the board’s continued support for the Phoenix purchase.

On one level, the piece seemed to be the State Board’s attempt to tell its side of the story — and address the concerns Freeman and Troy heard from lawmakers who said they hadn’t heard a case for the sale.

The guest opinion never went public. It’s unclear why.

In emails, the State Board outlined some basic protocol, saying UI and Little’s office should sign on before the guest opinion went public. But if UI or Little’s office spiked the piece, no one is saying.

Emily Callihan, a spokesperson for Little, declined comment. UI spokesperson Jodi Walker deferred to the State Board. In an email Wednesday, State Board spokesperson Mike Keckler wouldn’t directly say what happened.

“The (internal State Board) emails reflect potential informational strategies developed and discussed about the University of Phoenix acquisition proposal,” he wrote. “It was a fluid issue throughout the legislative session, with narratives changing almost daily. Given that, many of the strategies were never used including the draft op-ed, which wasn’t released.”

The State Board and UI also discussed a public meeting — a town hall of sorts, at the Lincoln Auditorium, the Statehouse’s largest hearing room. The parties even set a tentative date: March 6.

“The proposed informational hearing … obviously did not come to fruition,” Freeman said in a March 10 email to the board. “President Green was not supportive of the concept.”

Walker disputed Freeman’s account.

“President Green has always supported the concept of a meeting,” she said Wednesday. “The discussion was around format and timing. Because of the volume of work and timing of legislative actions, the calendar did not allow the meeting to come together.”

The mothballed guest opinion and the aborted public meeting both came just days after Freeman’s call to arms — his Feb. 25 email decrying legislative critics and news coverage vilifying the board and impugning its motives.

On Wednesday, Rep. Wendy Horman bristled at Freeman’s remarks. A skeptic of the Phoenix deal, and the co-chairperson of the Joint Finance-Appropriations Committee, Horman said legislative budget-writers have a duty to look after the state’s fiscal health. (Horman and other lawmakers have questioned UI’s claims that the $685 million purchase will not jeopardize the university’s financial health.)

On Wednesday, Horman, R-Idaho Falls, blamed the messaging problems on UI: “It felt like the University of Idaho was trying to hide information from the Legislature from the beginning, which in turn caused us to wonder why.”

March: A rollercoaster ride in the Senate

The legislative process is predictable in its unpredictability. Bills that appear to be greased for passage can hit unexpected snags. Sleeper issues can emerge late in a session, causing deadlock and delay.

As Phoenix supporters turned their attention to the Senate, hoping to save a troubled transaction, their moods changed almost daily.

By early March, it became clear that supporters wanted a Plan B — a bill to restructure the Phoenix purchase entirely.

They hoped a new bill would render the House’s adversarial Phoenix resolution moot. They also hoped that restructuring would address structural concerns about the deal the State Board endorsed in May.

The Senate never took up the House resolution. Privately, then publicly, the Senate bill took shape.

On March 5, representatives and lobbyists from Phoenix, Apollo and UI met with Little’s staff and State Board members for a “very productive discussion about finding a path forward,” Freeman told board members in a March 10 email.

The next Sunday night, in his March 17 update to the board, Freeman delivered a grim message.

“One day things seemed hopeful, and the next day not. Friday didn’t end well,” he said. “A member of the public has been particularly influential in convincing certain legislators that seemingly nothing could be done to make the transaction viable.”

Noting Statehouse opposition to a compromise — from House Speaker Mike Moyle, R-Star, and Senate JFAC co-chairperson C. Scott Grow, R-Eagle — Apollo’s COO said it was time to call for backup.

“This deal isn’t on the governor’s priority list,” Kwon said in a March 15 email to Liebich. “Given our situation and limited time, is there more that the governor can do to push this across the finish line?”

But in a sparse March 20 email — redacted by the State Board, which cited attorney-client privilege — Troy took a more optimistic view. “Better news that (sic) we’ve been used to … Phoenix or bust.”

On March 25, the Senate’s Phoenix bill finally emerged. On March 26, Troy and Phoenix lobbyist Kate Haas shepherded the bill through a supportive Senate State Affairs Committee.

That evening, in an email to Green and Liebich, Kwon noted that “things went very well” in the Senate. But Kwon predicted that Phoenix supporters would face “new challenges” from House leaders, Labrador’s office and state Treasurer Julie Ellsworth. “It sounds like the bill will die if we can’t successfully navigate those challenges.”

Kwon was proven right.

On March 27, letters of opposition from Labrador’s office and Ellsworth made the rounds in the Statehouse. And in an unexpected 19-14 vote, the Senate killed the last-ditch Phoenix bill.

March and beyond: Dead, or alive?

The Senate vote caught leading legislators off-guard.

Senate President Pro Tem Chuck Winder, R-Boise, said the late-breaking opposition from Labrador and Ellsworth probably flipped the outcome. Surprised by the Senate vote, Moyle declared the Phoenix deal dead.

On March 28, in an email to board members, Freeman delivered a similar diagnosis.

“Kurt (Liebich), President Green and I met with the governor this afternoon. It was determined that there is no viable path forward at this point for the University of Phoenix transaction. A statement will be issued by the University of Idaho — likely tomorrow.”

No such statement came. And in public comments, to the university and the State Board, Green has insisted the Phoenix deal is alive.

Two of Freeman’s more recent emails, also obtained by EdNews, spell out one possible roadmap.

Apollo has said it is willing to continue negotiating with UI — but it wants to be able to talk to other prospective buyers. If Apollo sells to another party, or hangs onto Phoenix, UI could receive a “breakup fee” that could offset some of its costs of consulting and due diligence. (On Tuesday, EdNews was first to report on this latest development in the Phoenix negotiations.)

And Apollo and UI plan to keep talking, for now, past an opt-out date Friday that would have brought the process to an end. UI says the talks will continue at least through June.

Ongoing talks bring the process that much closer to the start of the 2025 session, which will be marked by some new faces.

Freeman will be gone, after nine years as the State Board’s executive director and daily Statehouse presence.

The same goes for Winder, perhaps the Legislature’s most prominent advocate for the Phoenix purchase. He lost his May primary, in the biggest upset of a night that saw 15 incumbents lose their jobs.

And Green will be without several Statehouse allies, including Winder, House Education Chairperson Julie Yamamoto, R-Caldwell, and Rep. Megan Blanksma, R-Hammett. All of them received financial support from Green — in an unusual and high-stakes political gamble that won’t be soon forgotten by other legislators.

After 2024, and what Crane called a “full-on” lobbying pitch, the lawmakers who do take office will likely demand a say on the purchase. If the Phoenix deal is still in play when the 2025 Legislature convenes, it will again be a focal issue.

Senior reporter and blogger Kevin Richert specializes in education politics and education policy. Follow Kevin on Twitter: @KevinRichert. He can be reached at krichert@idahoednews.org