Washington Supreme Court sides with state in school building costs suit

Out of options to fund repairs to its decaying buildings, a 400-student school district in one of Washington’s poorest counties launched a legal challenge against the state two years ago.

On Thursday, the Wahkiakum School District lost in a unanimous ruling from the Washington Supreme Court. Local taxpayers are still expected to share in the costs of maintaining and constructing school buildings, even if, like Wahkiakum, they haven’t approved a bond in 20-plus years.

But the debate over the state’s investment in school construction funding costs will continue. While the opinion says the state isn’t required to cover 100% of basic school capital construction costs, it offers a legal path for school districts to challenge how much and where the state is currently chipping in.

“They’ve left the door open,” said Wahkiakum Superintendent Brent Freeman.

There is little reprieve for school districts that fail to pass a bond in Washington state, which are often the smallest and poorest. Without a bond, these districts are also locked out of qualifying for the state’s largest construction assistance program. Another state grant program, which is more flexible and is aimed at small school districts, hasn’t offered sufficient funds for substantive repairs. It was funded for about $100 million in the last legislative session.

Wahkiakum says it needs at least $50 million for critical repairs and to remodel its high school, which hasn’t had major renovations since it was first built in 1962. Rainwater drains from ceilings in both of the district’s school buildings, bathrooms flood regularly and there isn’t proper equipment for science experiments. Teachers hand out blankets in the wintertime to students because classrooms get so cold.

Just last week, Freeman said, his staff had to set up two garbage cans to collect water drainage.

Justice Charles Johnson acknowledged the bind that districts face in his concurring opinion.

“The State should not selectively deny funds for high quality educational environments based on the district’s lack of local monetary support,” he wrote.

Senate capital budget writer Mark Mullet, D-Issaquah, said while he agreed with the Court’s decision, “We’ve still got to find more ways to help build and maintain schools in districts with low property values.” Two bills in the last legislative session would have kicked in more state assistance, but they stalled and died in the House.

In a statement, state Superintendent Chris Reykdal proposed the Legislature remove the supermajority requirement for bond passage.

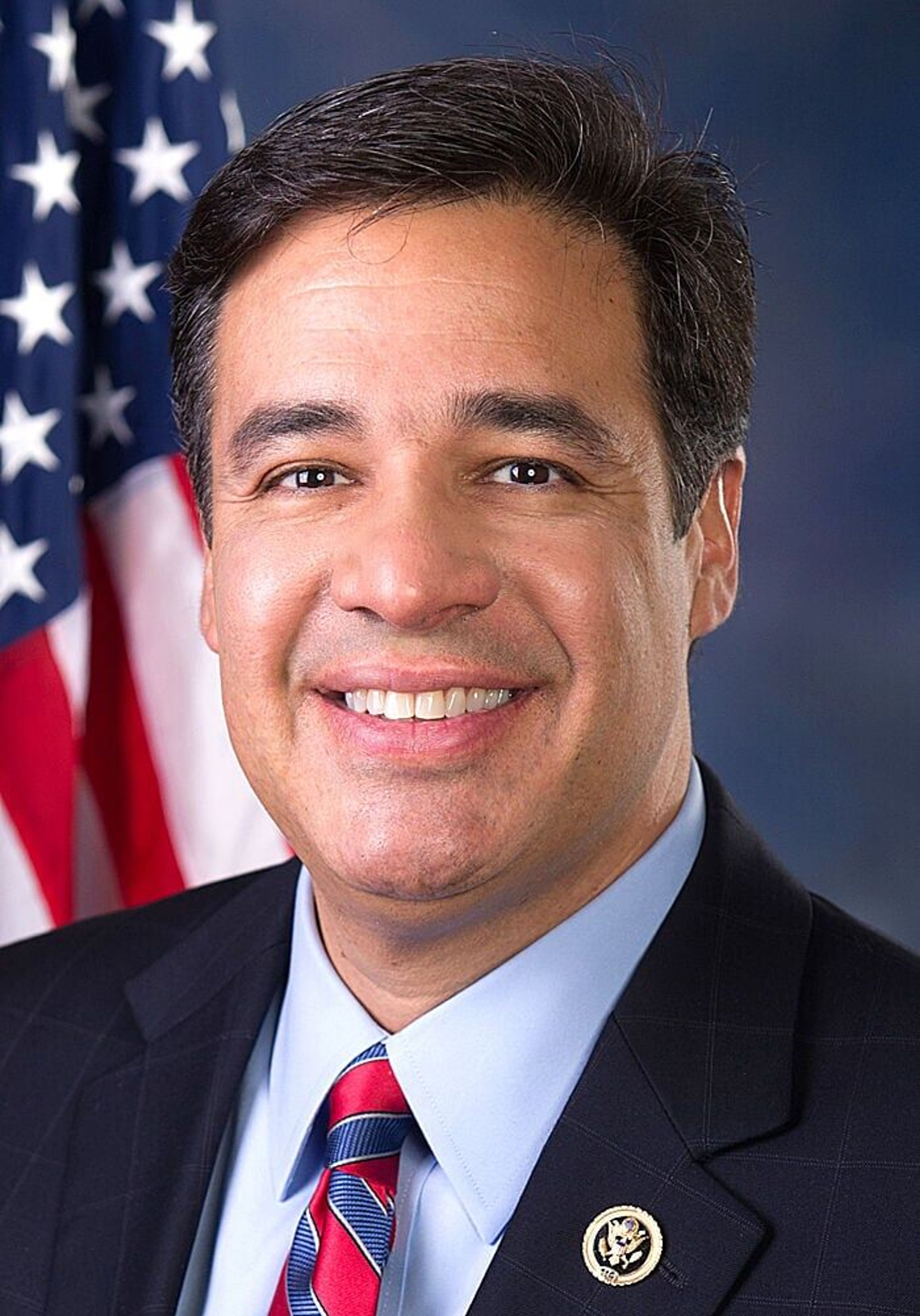

State Republican Party Chair Jim Walsh had harsher words for the Court.

“Imprisoning children in dilapidated school buildings will drive even more Washington families away from the school system. They will choose private schools and home schooling instead. And the public school system will suffer,” he wrote in a statement.

Had the Court sided with Wahkiakum, it would have meant another whirlwind change in the state’s education funding system. McCleary v. Washington, decided by the Court in 2012, determined that the state was responsible for fully funding the basic costs of educating students.

The case rested on the state’s constitutional promise to make education funding its paramount duty. The ruling forced the Legislature to allocate billions more for education funding.

Wahkiakum, represented by Seattle lawyer Tom Ahearne — the attorney who won the McCleary case — made the same argument for school buildings. But the Court rejected this premise.

“It is clear that the constitution as a whole treats funding for school capital costs differently than it treats funding for other education costs,” the decision said.

It’s way too soon to know if the district will choose to move forward with another lawsuit, Ahearne said. The district’s legal costs are estimated to be north of $300,000. Districts have donated around $100,000 to a legal fund.

But he says he’s personally invested in pursuing it further, saying the state’s current school construction funding system creates a “caste system.” Under the current funding structure, taxpayers in districts with wealthier property valuations are shouldering much less per capita for school facilities.

“Wahkiakum needs to move forward on something. Because frankly those buildings are not safe.”