Wastewater testing could be crucial in virus battle

UI joining up with other colleges and universities in Idaho to watch for COVID-19 spikes in communities' wastewater

Wastewater testing at the University of Idaho, along with partners at Boise State, Idaho State and Lewis-Clark State, is helping to pave the way for a new method of tracking and predicting spikes in COVID-19 cases at a community level.

The team at the UI first started its work in 2020, after the city of Moscow requested help to monitor COVID-19 levels in wastewater, said Erik Coats, a professor of environmental engineering and lead for the UI testing program.

Now, funding from the CDC’s National Wastewater Surveillance System is expanding those efforts in collaboration with Idaho’s four public colleges and universities.

The universities are collaborating with the Idaho Bureau Of Laboratories, with the hope to eventually have roughly 35 testing sites statewide.

The UI will get about $825,000 over two years through funding from the CDC, Coats said, which included spending roughly $140,000 on new equipment to standardize all labs. Thanks in part to their early start, they’re currently the most active wastewater testing lab in the state, tracking data from Moscow, Genesee, Juliaetta, Kendrick, Troy and Potlatch.

Previously Moscow used data from the private company Biobot Analytics, which inaccurately estimated in the summer of 2020 that the city would have roughly 1,800 COVID-19 cases when Latah County had only confirmed 46.

“To date, we have no ability to correlate wastewater concentrations with a number of infections. It's too dynamic at the individual level,” Coats said. “Clearly, they jumped the gun.”

Coats is critical of that type of jump, he said — when science isn’t communicated carefully, the public loses trust in tools that could help them. But even though wastewater can’t be used to measure case numbers, it’s a powerful and completely anonymous early warning system for changes in COVID-19 activity at a community level.

The value of wastewater testing is watching trends over time, Coats said. While they can’t predict exact numbers, the team has been able to predict case spikes by roughly five to seven days before they appear in clinical data sets.

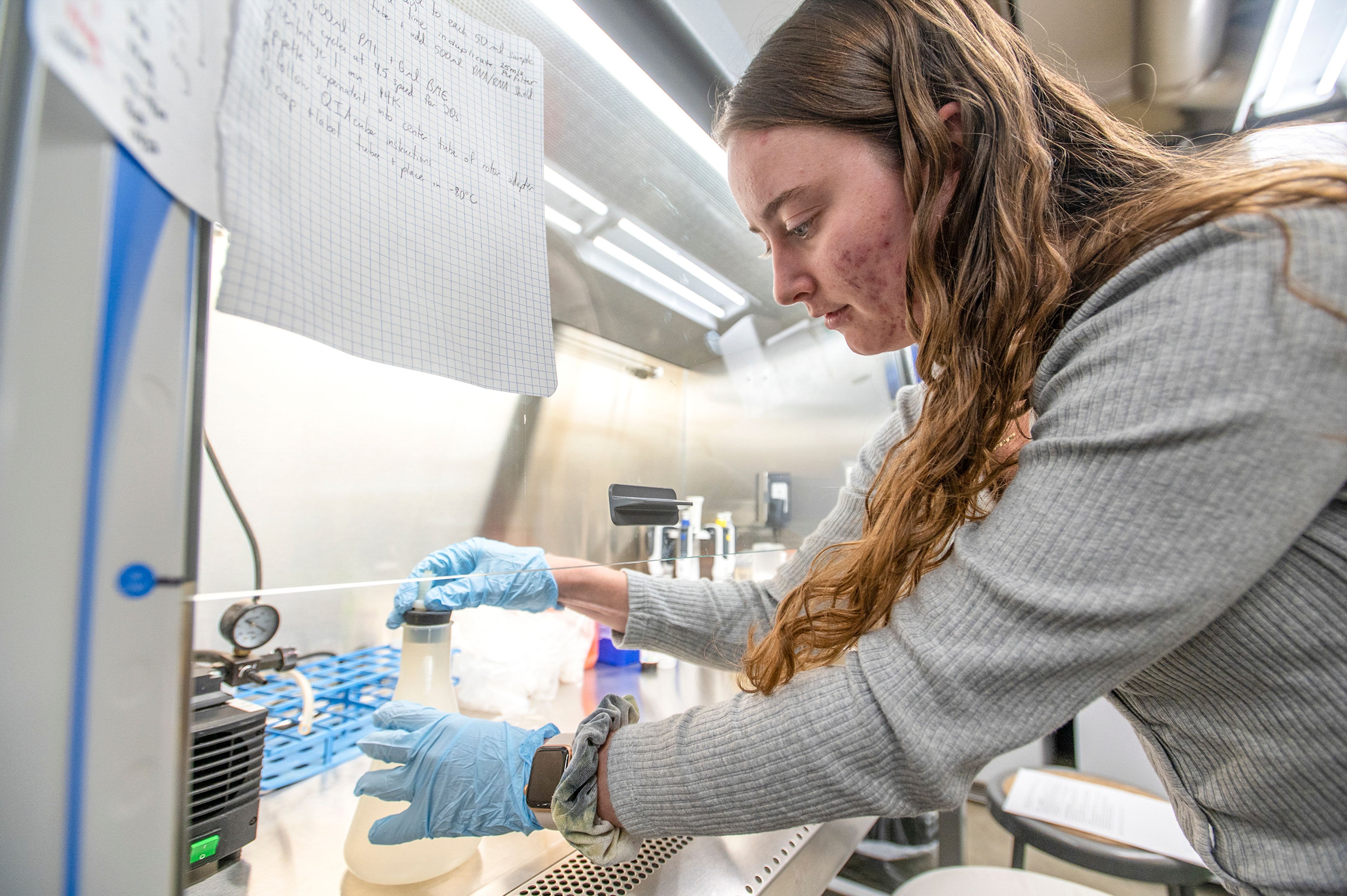

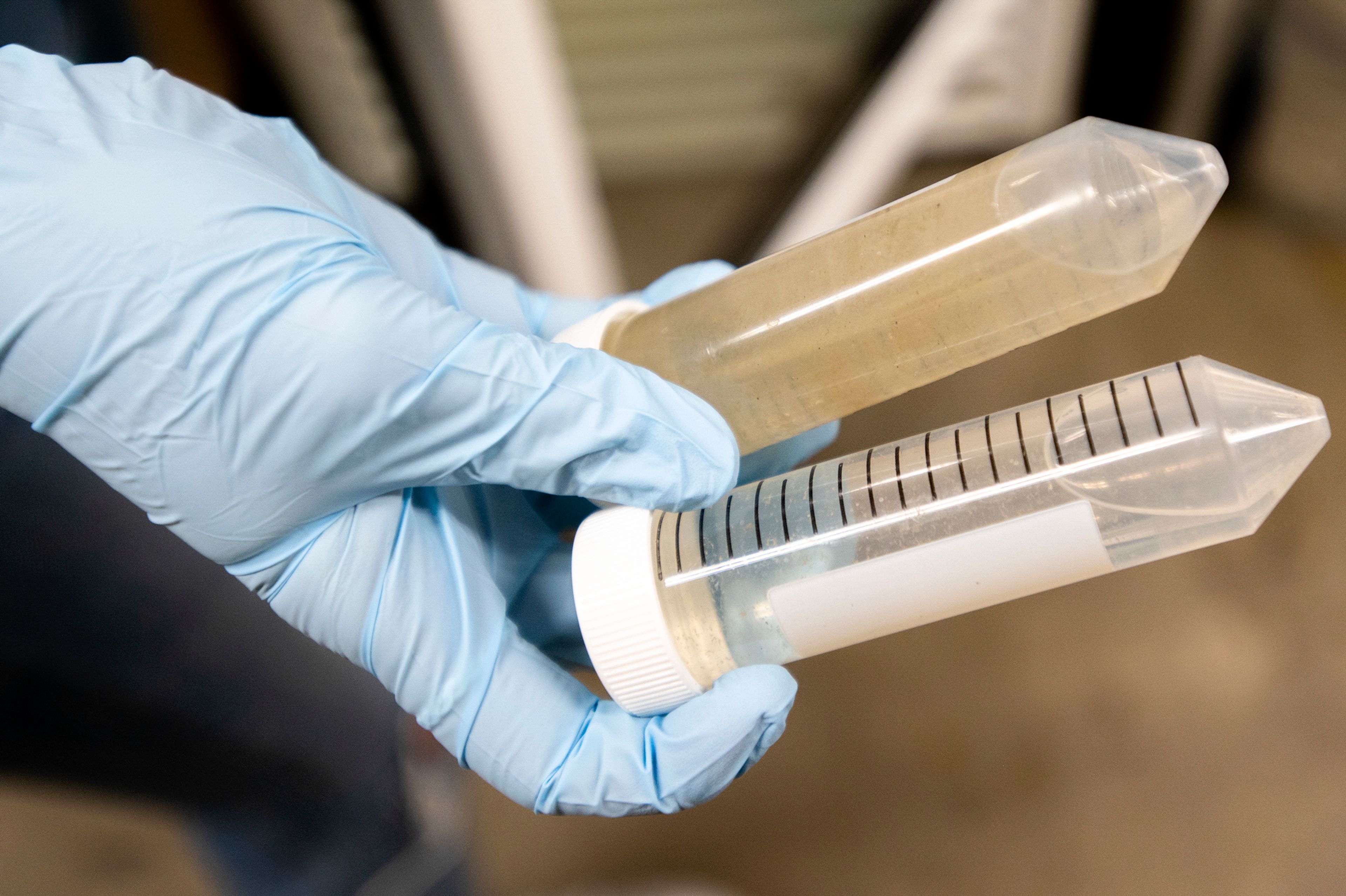

To test the levels of the virus in wastewater, a technician uses a filter to get concentrated samples, which are then put in a machine to lyse, or break down cell membranes, and extract RNA samples. Those samples are then run through a digital PCR test.

“It basically amplifies everything that's there, so you can back-calculate to how much was the original concentration,” said Solana Narum, a lab technician on the UI team and soon-to-be Ph.D. student.

Wastewater monitoring has become even more valuable as clinical data becomes less accurate with the increased availability of at-home testing kits, which aren’t reported to health authorities. Even before that was the case, there were people who never got tested.

“(Clinical data) only represented those who were ill, and who went to a clinic to get tested. The wastewater testing captures the entirety of the community,” Coats said. “It's the only method that captures the entirety of the community without requiring people to do anything.”

Wastewater testing also has implications down the road for monitoring other illnesses within the community, such as influenza, and even narrowing down the source of an outbreak.

During the 2020-21 academic year, the team also measured 10 sites at the university. The data helped administrators make health decisions and notify living groups of potential exposure, said Thibault Stalder, a research support scientist in the Department of Biological Sciences.

“You could see when there's people that are getting sick (in) the building, you will see the wastewater spike,” he said. “That spike would help the university administration. They would see that fraternity or sorority building or that dorm getting people sick, so then they would send an email and say, ‘Please get tested.’ So then they could get everyone tested, and then they could isolate the individuals.”

As data from more collection sites becomes available, more people will be able to visit the CDC website to view that data in their region. Coats said he hopes the availability of that data may help quell some of the political divides over COVID-19.

“We can help provide data that helps them make decisions on whether they're going to mask up, whether it's time for a booster,” Coats said. “There's information on the community health, and people can make decisions on their own.”

Sun may be contacted at rsun@lmtribune.com or on Twitter at @Rachel_M_Sun. This report is made possible by the Lewis-Clark Valley Healthcare Foundation in partnership with Northwest Public Broadcasting, the Lewiston Tribune and the Moscow-Pullman Daily News.