Every so often, the Pullman City Council will be asked to vote on a project the size of a small residential community. About halfway through a council meeting, the mayor will give the floor to the city planner who introduces the project. Using a site plan, now projected on a screen, the planner will point out boundaries, acreage, basic building boxes, parking, sidewalk and one or two other things.

Beyond that, the world seems to fall off the map, a matter of someone else’s business. There could be a brothel across the street and you wouldn’t know it. No crosswalks, play structures, bus stops — nothing to suggest that life on the other side of the street goes on. Having mentioned a few self-evident facts about the number of units and the like, the planner will then open the floor to questions.

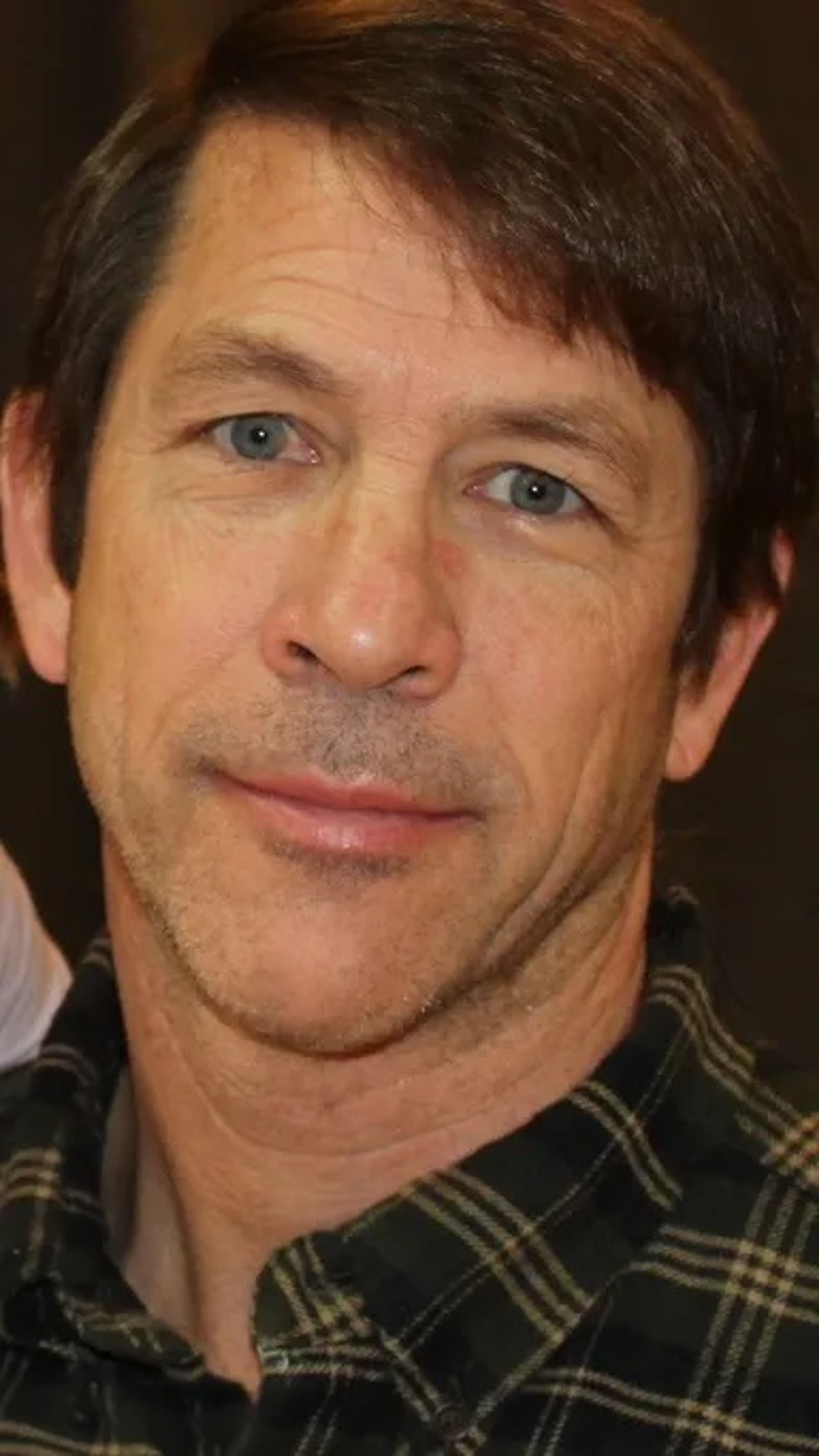

Having had no previous training in either planning, architecture or the like, council members will look baffled, unsure what to make of the drawing presented to them. And so they will start asking random questions. Not bad questions, but just not particularly relevant to the concerns at hand, namely, how does the residential community up on the screen enhance livability.

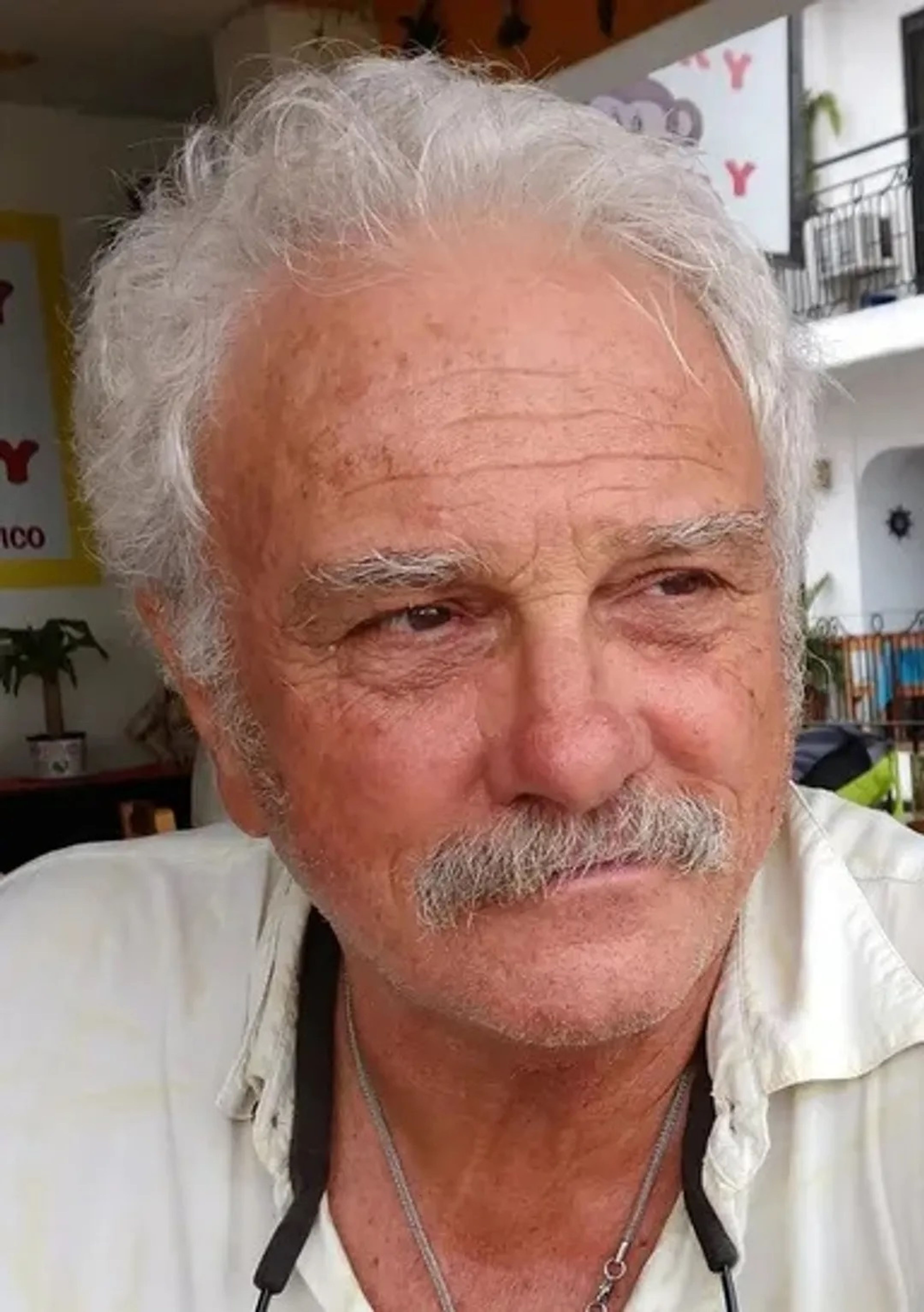

Questions related to such matters as child care and the elderly are left behind, but so are walkability, environmental sustainability, social and racial justice. Today we have collectively agreed that there is more to life than mere profit, but a need to include in our efforts concerns for climate, soil, animals, meaningful work and much more. Profit will, of course, always be important but today we have come to understand it less in binary terms and more as a feature of a much larger complex system of care and wellbeing.

By the time planning projects make it to the city council for debate they should be well vetted next to a large web of economic, social, environmental and cultural effects. Developers, by then, should have demonstrated their impact through drawings that transcend the singular site plan, including diagrams and perspectives showing activities promoting health and wellbeing — children playing, people interacting, animal habits. How about features that harvest natural energy, such as solar and wind tools, feeding the proposed community but then restoring excess supply back to the remaining city.

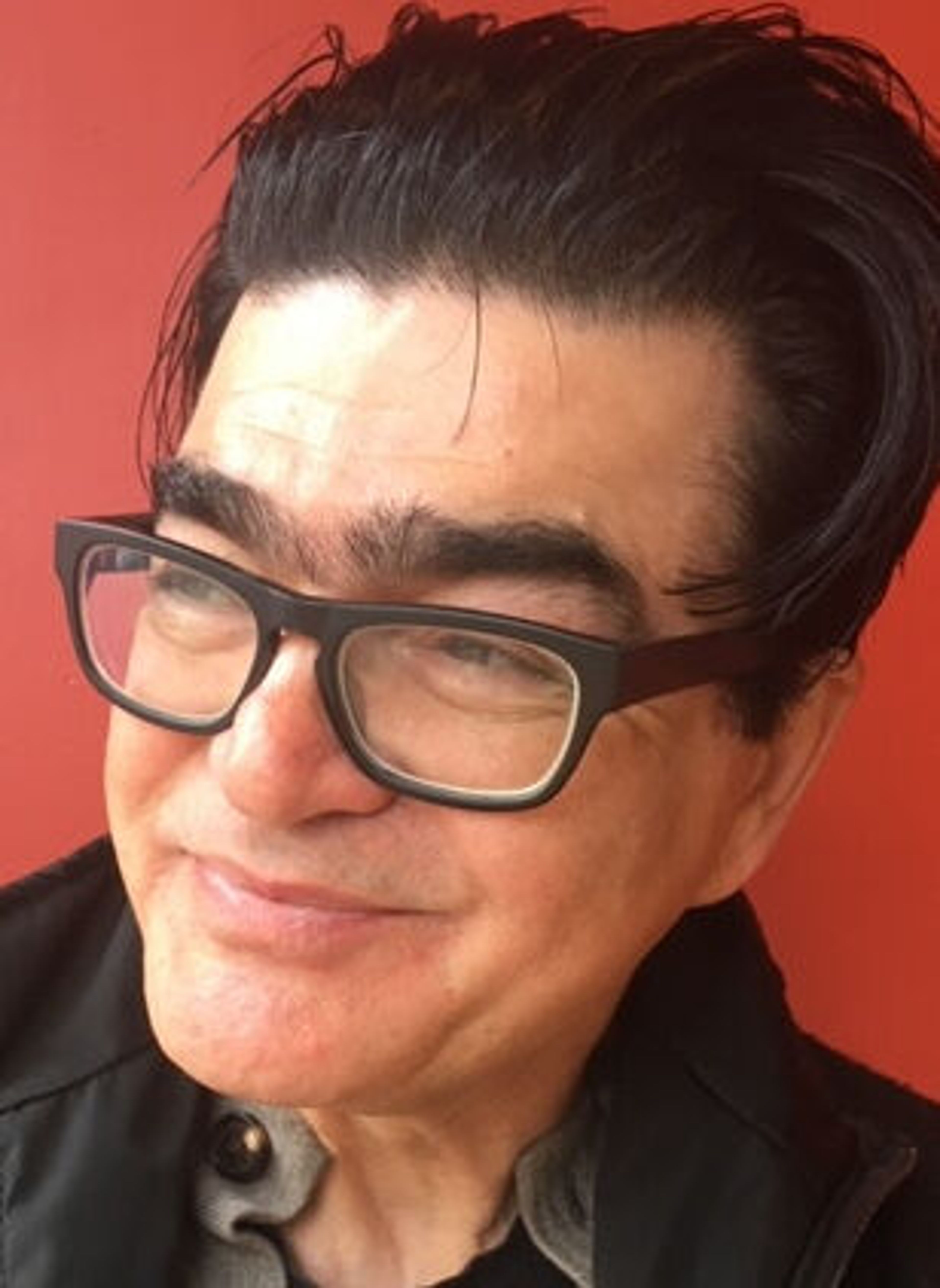

The city planner back at the podium knows the importance of such drawings but has no recourse. Look at him speak and you can tell he is a little embarrassed by what he is showing. His face is downcast, his language limited. There is no joy in what he is saying, no hope, no pride. He dreads the questions from the council, not because he does not like them but because he has little to offer in terms of meaningful answers.

He may defer to the planning commission for that. But even that august body of individuals has little or nothing to offer, again, not because they lack intelligence, but because they too had been dealt the same limited information as the city planner. Consider their response to the Hidden View residential development back in April, located by Kamiak Elementary School.

Having heard from the developer and one or two proponents of the project, including important comments about “stormwater runoff,” its members quickly moved to forward the proposal to “the city council with the recommendation for approval, subject to the eight conditions as prepared by staff.” Of which the only one condition that seemed to have a remote impact on quality of life matters was a mechanical statement about sidewalks.

And that’s it. No mention of any of the concerns listed above and which in today’s practice represent a standard response to a world split apart by economic, racial and political divides. How can this be? How can we vote on an emerging community without the proper information to do so? How can we pass along a consequential development without empowering council to know how to debate the issues? Which of course they don’t.

The community deserves better. It is well and fine to promote development, but with that also comes the responsibility to enhance life, foster relations, encourage art, expansion of habitats, indigenous culture and more. Time to take a hard look at the way we do things.

Rahmani has been with Washington State University since 1997 and is an associate professor in the School of Design and Construction.