When the Vandals ruled the Big Sky

As the current UI football team adjusts to life at the FCS level, it would do well to take a cue from the great Vandal teams of the 1980s and ’90s

In 1980, Idaho football aficionados didn’t really have much encouragement. It had been a wait — nine years — since the Vandals had won a Big Sky championship.

They’d suffered many a losing season, to say the least. The notion of back-to-back winning campaigns was about as serious a topic of conversation back then as UI running the spread offense, gunning it downfield seemingly to spite Big Sky opponents.

But then, a betoken arose in the form of a small-town kid, a mid-sized, four-sport athlete — baseball, basketball, track and football. This kid had run the wishbone offense as a wiry quarterback at Kamiah High, a 75-mile trek southeast of Moscow down U.S. Highway 12.

“I could obviously run. That’s why I went here. We ran the veer, but I could also throw,” said Ken Hobart, an all-time great for UI at field general. “I was in the right place at the right time.”

Right place, right time — perhaps one of the trends of UI’s 14 years of Big Sky supremacy before moving up a division, an era spanning from 1982 to 1995. It’s been termed the “Decade of Dominance,” though maybe “Decade-plus” would be more fitting.

UI etched an aberrant 14 straight winning seasons, produced four consecutive long-term quarterbacks, three notable coaches — four, if counting Chris Tormey’s first year in 1995 — who all are now hailed by the Idaho faithful, and went to the Division I-AA playoffs 11 times, making the semis twice.

They did almost all of it in a dimly lit Kibbie Dome — then “the best stadium in the Big Sky by far,” said former coach Dennis Erickson — with a student/student-athlete shared weight room, playing on skin-destroying AstroTurf while donning “Pride” gold and black — a “Killer V’s” look.

“I fell smack dab in the middle of it,” said 2006 College Football Hall of Fame inductee John Friesz, who led the Vandals in the late 1980s. “Hobart, Gilby (coach Keith Gilberton) and (coach) John L. (Smith) should take as much credit as anybody. … We were sort of carrying the torch, and it was easier to keep it going than sparking the fire.”

Basically, it began with a fortuitous choice, then an incidental sign of fate; Hobart wanted to play baseball at Lewis-Clark State out of high school after taking in some games during the fall of 1979, so he enrolled there. Chance is a funny thing, though. Hobart and then-Warriors coach Ed Cheff ended up “butting heads,” leading to Hobart’s decision to transfer to UI with designs to play for the Vandal baseball club.

“Two weeks after I transferred, they ended up dropping the baseball program,” Hobart said. “Now what do I do?”

Well, what else but walk on to the Vandal football team, which hadn’t produced a winning season since 1976.

Hobart worked his way from the “No. 7 spot” up the depth chart by irking first-team defenders in practice as a reserve quarterback.

“The day before the alumni game (UI used to pit contemporary players against recent graduates for its spring game) the coaches said, ‘You’re gonna start the game tomorrow night,’ ” Hobart said. “I played the first quarter and a half, then coach said, ‘You’re done for the night.’ I’m like ‘what?’ and he says, ‘Because I’ve seen enough. You’re my starter come fall.’ ”

The following Monday, Hobart was offered a scholarship.

He began as a decathlete-type runner in coach Jerry Davitch’s veer offense. That translated to less than 2,000 yards passing per year in his two opening seasons. After a disappointing 3-8 mark as a sophomore in 1981, a former athletics employee — after having “one too many beers” — inquired to Hobart as to where he’d transfer next season.

“We ran the same offense as the University of Houston … we’d sent tape over to them. So I actually was thinking about transferring,” Hobart said. “But when they changed the rule (redshirt rule that afforded Hobart an extra year) I said, ‘I’m staying and I’m gonna show … I can throw.’

“Lo and behold, they hire Dennis Erickson.”

Hobart’s introduction to the program may have foreshadowed success, but when Erickson stepped foot on campus in late 1981, overarching prosperity began to take shape as a long-running reality.

“When I was an assistant for Ed Troxel in the late ’70s … a big piece of my heart went up there to stay in Moscow,” Erickson said by phone this week.

He was just coming off a three-year stint as the offensive coordinator at San Jose State under Jack Elway. There, Erickson implemented a spread offense, an anomaly in the Big Sky.

“It all started at San Jose, when we were spreading out people before anyone was really doing it at all,” Erickson said. “At that time, it was all about matchups … our quarterbacks dealt well with the spread, and I think that turned (UI’s) program around.

“As soon as we got there we were putting that offense in. … Kenny was one of the best and we were fortunate to have him.”

A turnaround might be an understatement from the storied skipper, who’s traversed almost every level of NCAA football, the pros and now finds himself at age 71 as the new coach of the Alliance of American football’s Salt Lake City troupe.

Really, the program’s largely hapless past all but dissolved thanks to Erickson and Co., and was supplanted with a new culture, one that expected winning from all angles — winning support, winning recruits and most importantly, winning games.

“Football was king,” in the words of Smith. UI became I-AA royalty in the Northwest during and after his tenure. The dome “never had under 8,000 in it” and “the tailgates started at 3 o’clock on Friday after classes were over,” said Hobart.

To get there, Erickson started right away recruiting from scratch, and accumulated a stout gang of regional guys and California talent. He brought in some juco quarterbacks to challenge Hobart — then a junior — but it quickly became clear that nobody was going to leapfrog the “Kamiah Kid.”

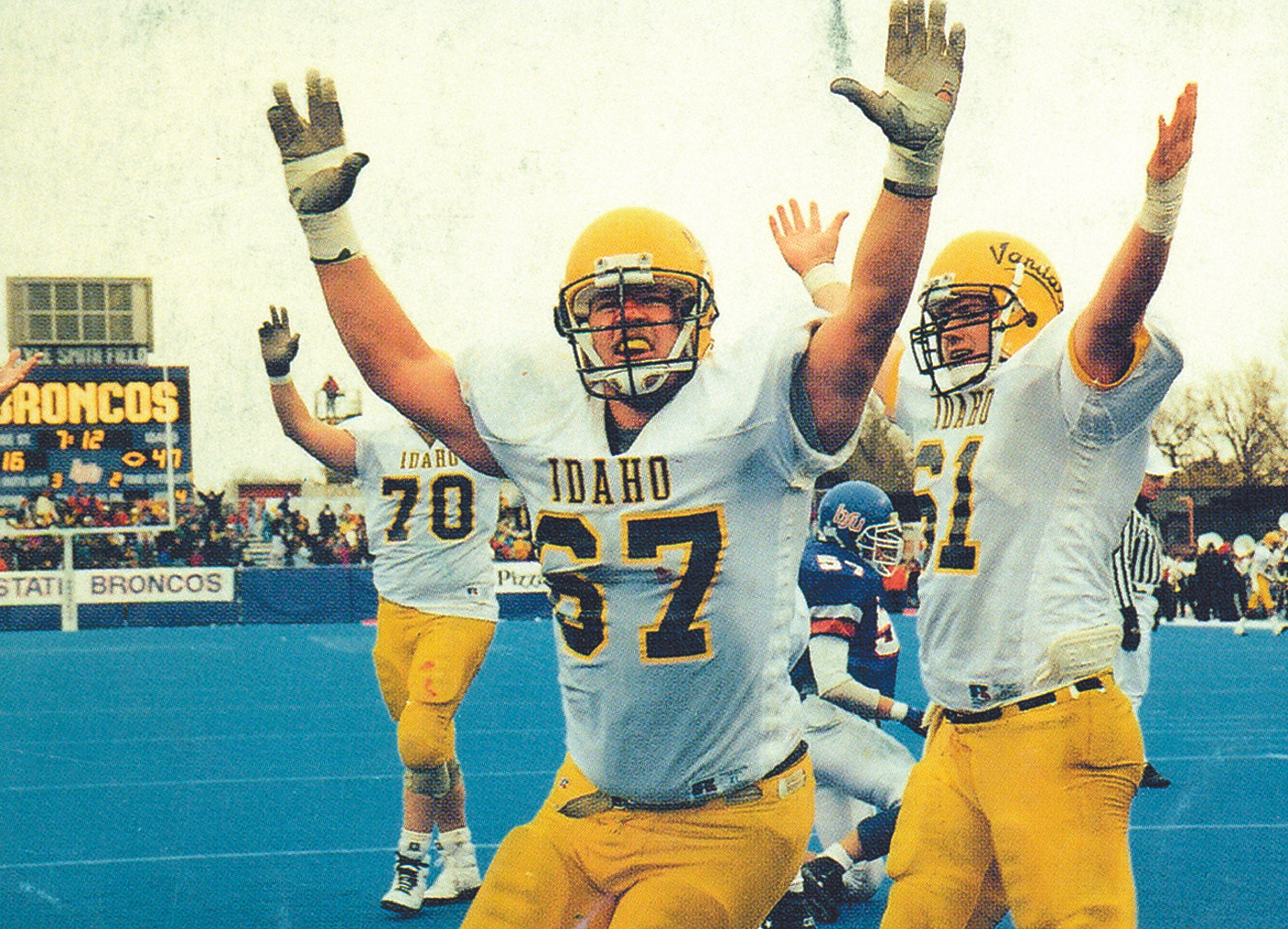

With now-New Orleans Saints receivers coach Curtis Johnson to throw to, and with now-Raiders O-line coach Tom Cable as his right guard, Hobart threw for over 3,000 yards in 1982 — almost triple of 1981 — and spearheaded the Vandals to their first win over Boise State (in Boise) in six years.

The Vandals also finished with a 9-3 regular-season record — then the program’s most wins in a season. Hobart earned an All-American award and UI solidified its first-ever appearance in the I-AA playoffs, a one-score loss to eventual-champion Eastern Kentucky in the quarterfinals.

They tied in the regular season with Montana for the Big Sky title, but lost the head-to-head tiebreaker.

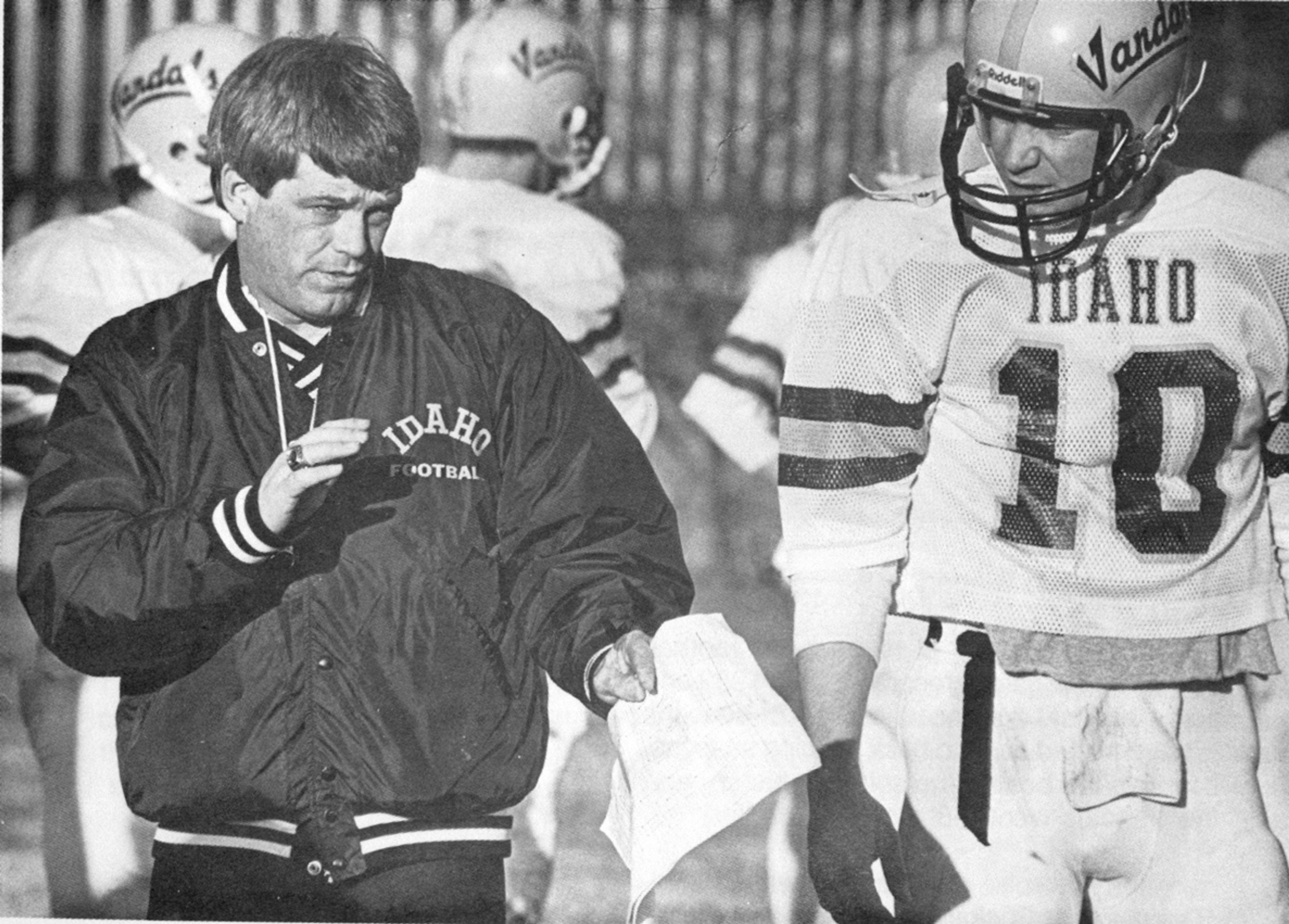

That year, Erickson also put together a staff that featured such names as Smith and Gilberton, who successively carried the torch after he left for Wyoming in 1986.

“We were very successful in the four years I was there,” Erickson said. “Then Keith took it over and then John, who was an assistant, took it over. The whole thing just fell into place once we started winning.”

After throwing for over 10,000 yards in his career, helping cement the Vandals as a conference powerhouse and having nearly been blinded by potato starch — Montana spectators used to huck sliced spuds at UI players in Missoula — Hobart was off to the Canadian Football League, where he aided the Hamilton Tiger-Cats to a Grey Cup in 1986. Before that, though, he said Erickson asked one more thing of him in 1984.

He was to go up north to Coeur d’Alene High and check out the athleticism of a Viking that Erickson had his eyes on, a player who’d become the third straight uber-successful UI quarterback and perhaps the most heralded among Vandal fans: “Deep Friesz.”

Not long later, Hobart phoned Erickson.

“I think this guy’s gonna go to Idaho,” he said.

Sure enough, Hobart’s prediction was spot on. Friesz had two options: Idaho and then-lowly New Mexico.

“I only started one year in high school; I was a late-bloomer,” Friesz said. “I had two offers: one to Idaho and one to New Mexico, which had the longest losing streak in I-A football.”

Friesz directed himself to UI, where he redshirted in 1985 and spent a season behind Scott Linehan, the now-Dallas Cowboys offensive coordinator and father of recent UI standout Matt.

It was Erickson’s last season, and Linehan abetted the result — UI’s first outright Big Sky championship since 1971, a No. 5 ranking and another playoff appearance.

“We had to go recruit (the region), we had to get skill there,” Erickson said. “Then we continued to recruit guys like Scott Linehan — from Sunnyside, Wash. — and John Friesz (who) took the program forward.”

After Erickson was gone, off to eventually earn two national championships with the Miami Hurricanes (1989, 1991), his two-year offensive coordinator, Gilbertson, was handed the reins.

Friesz made his first splash on Sept. 5, 1987 against D-II Mankato State. Friesz distinctly remembers sitting in his car pregame, telling himself how he was not ready for it. A few hours later, he had passed for over 300 yards and easily scooped up his first win.

“From that moment on, I felt very comfortable,” Friesz said. “I was always between 300 and 400 yards, with consistent scores and wins. … Every week was the same thing.”

Every week for three years, that is. Buttressed by luminaries like Mark Schlereth in the trenches — a 12-year NFL player and now-renowned sports commentator — and D-end Marvin Washington, pocket-passer Friesz captained the Vandals to back-to-back-to-back Big Sky championships.

That included three more wins over BSU, driving UI’s streak to eight, and three consecutive regular seasons with UI finishing ranked top five in the country.

For two of those years, it had a jovial coach in Gilbertson — Friesz recalls him as “the funniest coach I’ve ever had” — who’d “poke and prod” players with quips, but always get positive results at practice. All UI had to do was lean on the group camaraderie and trust the staff, and fans, who were absolutely enjoying the party, could continue expecting wins.

“It was a big deal to go to games,” Friesz said. “After and before I was there too.”

In 1989, Smith’s first year as head coach and Friesz’s final, UI took back the Little Brown Stein on ESPN at home against Montana, Friesz was named the Walter Payton Award winner and, of course, they logged an 8-0 Big Sky record, the only time the Vandals have ever gone unbeaten in conference.

And despite his accolades, Friesz defers the credit to his teammates.

“There’s no smoke and mirrors. I had ability, but also limited ability,” Friesz said. “I was completely dependent on the O-line giving me the time … and I was dependent on receivers stopping or breaking routes exactly when they needed to.

“Those guys were a tremendous part of my success. … I know they see their names (up in the rafters) right up there with mine.”

Under Smith and new quarterback Doug Nussmeier — the Walter Payton winner in 1993 and currently tight ends coach for the Cowboys — UI’s success didn’t halt.

Smith, who Friesz said “cared passionately about his players,” posted a UI-best 53 wins in six seasons, won two Big Sky titles and made the playoffs every year but 1991.

“I look back at my coaching career, having coached all over the U.S. from the SEC to Big 10 to at a D-II school right now, and that was probably the most fun I’ve ever had in coaching,” said Smith, who now heads Kentucky State but plans on retiring in McCall. “It seemed like our kids were just on board … we didn’t have to discipline our team. They took care of it.”

In 1993, UI made it all the way to the semifinals after edging Northeast Louisiana and Boston U in the playoffs. Ryan Phillips, a four-year starter at defensive end from 1993-96, former New York Giant and now UI’s radio broadcaster, offered an account of the playoff loss to Youngstown State.

UI was always tabbed as underdogs back then, said Phillips, even during the stretch of immense success. In Ohio, in minus-20 degree temperatures, the Vandals proved they could hang with I-AA’s “big boys.” They were one of them, in fact.

“It came down to a controversial call. Doug threw a touchdown pass, but the refs said he caught it out of bounds,” Phillips said. “You could see where his toes drug from where his tracks were in the snow.”

But it was “all for naught.” That was perhaps UI’s best shot to log a national championship.

The 14 seasons of prosperity may not have produced a national championship, but they proved what can be accomplished through a string of achievements.

Those past years aren’t all for naught, when considering what they culminated in: a chance for the Vandals to compete at the I-A level, and notch a 3-0 bowl record in 22 seasons there.

Chris Tormey took over as coach in 1995, UI’s final I-AA season, and again, the Vandals made the playoffs. The triumphs of the former years shone through, though, and Tormey was able to take the momentum forward into a 1998 Humanitarian Bowl victory over heavily favored Southern Miss.

Those may have been “the days” for Vandals fans to dream of when faced with turmoils like the present. To each of these former players and coaches, despite the currently split fan base on FBS versus FCS play, UI “can get back there again.”

They say it’s all about the “culture” that was implemented — “everything’s a lot easier when you’re winning,” said Erickson. Former linebacker (1983-86) and assistant coach Mike Cox said the bar was always set higher for incoming players, and none of the coaches missed a beat.

“Every year we strived to reach the goals and set goals for the next,” said Cox, now an assistant at UTEP. “There was a lot of pride in being a Vandal because of what all the guys before you achieved.”

It also helps when you consistently handle your rivals. UI took BSU down 12 times in a row (1982-93), and went 119-52 between 1982 and 1995 — when the “Decade(-plus) of Dominance” was sparked by Erickson, then carried forward into a new chapter by Tormey: I-A play.

And don’t forget, current UI coach Paul Petrino was on that staff of supremacy from 1992-94. It was a cycle of success back then, and the Vandals now hope they can reignite it, and carry that torch forward when they get Portland State on Saturday at 2 p.m. for their first Big Sky home game since a Nov. 18, 1995, takedown of Boise State.

Colton Clark may be reached at cclark@lmtribune.com, on Twitter @coltonclark95 or by phone at (208) 848-2260.