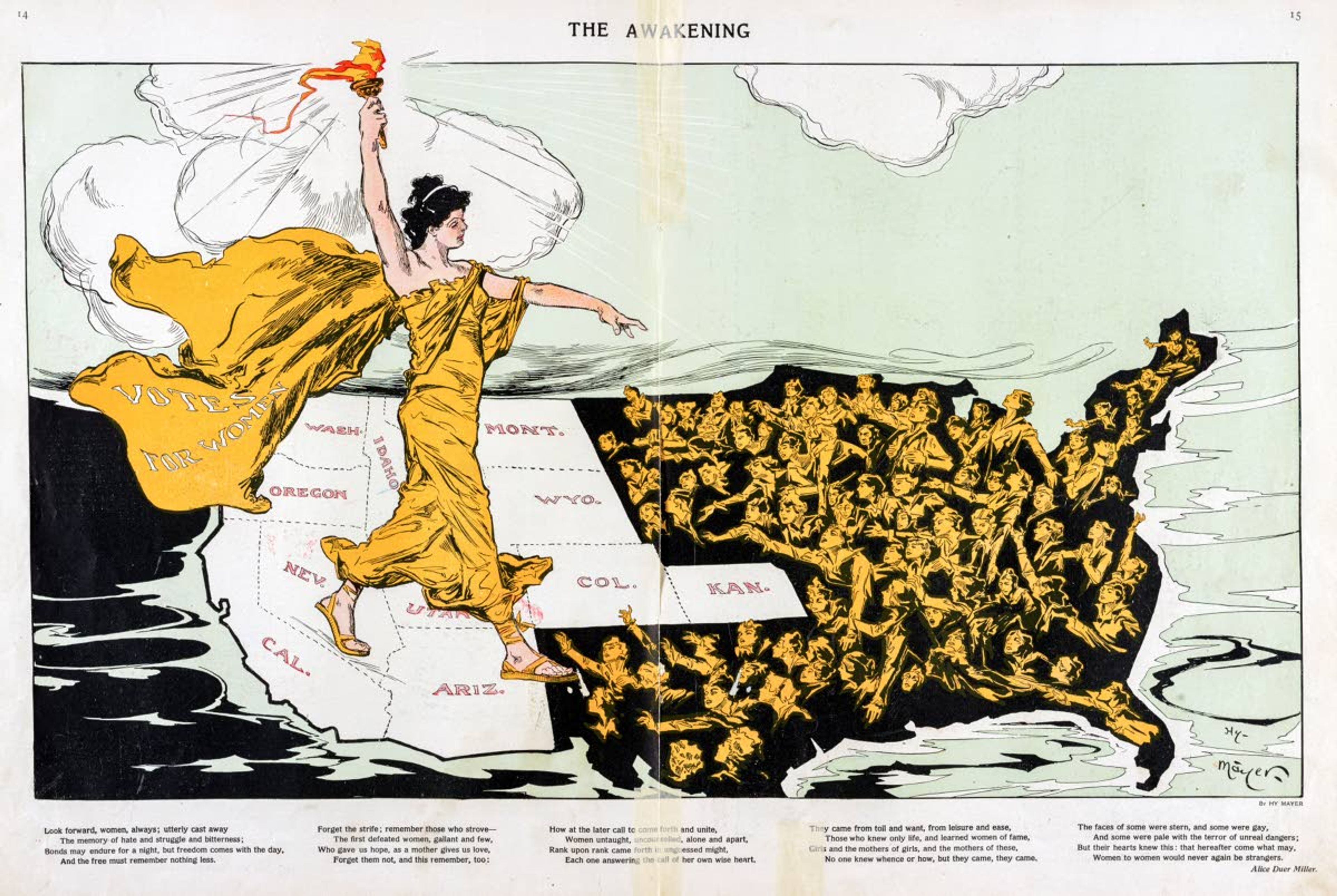

America’s West led the way in women’s right to vote

The fight for women’s suffrage was won in the West long before it was achieved nationwide, and Idaho was a leader in the fight along with Wyoming, Colorado and Utah.

Idaho was the fourth state to extend suffrage to women. State voters agreed in 1896 to extend voting rights to women, but it took a court ruling for the vote to stand.

Women’s suffrage in the United States was full of fits and starts. New Jersey women enjoyed full suffrage rights from 1790 until the Legislature took it away in 1807. Kentucky gave head of household women the right to vote on taxes and schools in 1838.

But women’s suffrage would not take hold anywhere east of the Mississippi in the 19th century, even as the national movement for the right to vote would officially begin in a women’s rights convention at Seneca Falls, N.Y., in 1848.

Women’s suffrage first was realized in Wyoming Territory in December 1869. Idaho Territorial Legislature had a bill to extend voting rights to women a year later, but the bill died in a tie vote, Idaho State Historian HannaLore Hein said.

Idaho made another attempt that failed in 1872. Utah had passed women’s suffrage and then took it back, Hein said. Women continued to advocate for suffrage in Idaho through the 1870s and 1880s.

They would win the right to vote in school-related laws in 1885 in Idaho Territory, Hein said.

“Partial suffrage gave women a foot in the door where they could flex their civic muscles,” she said.

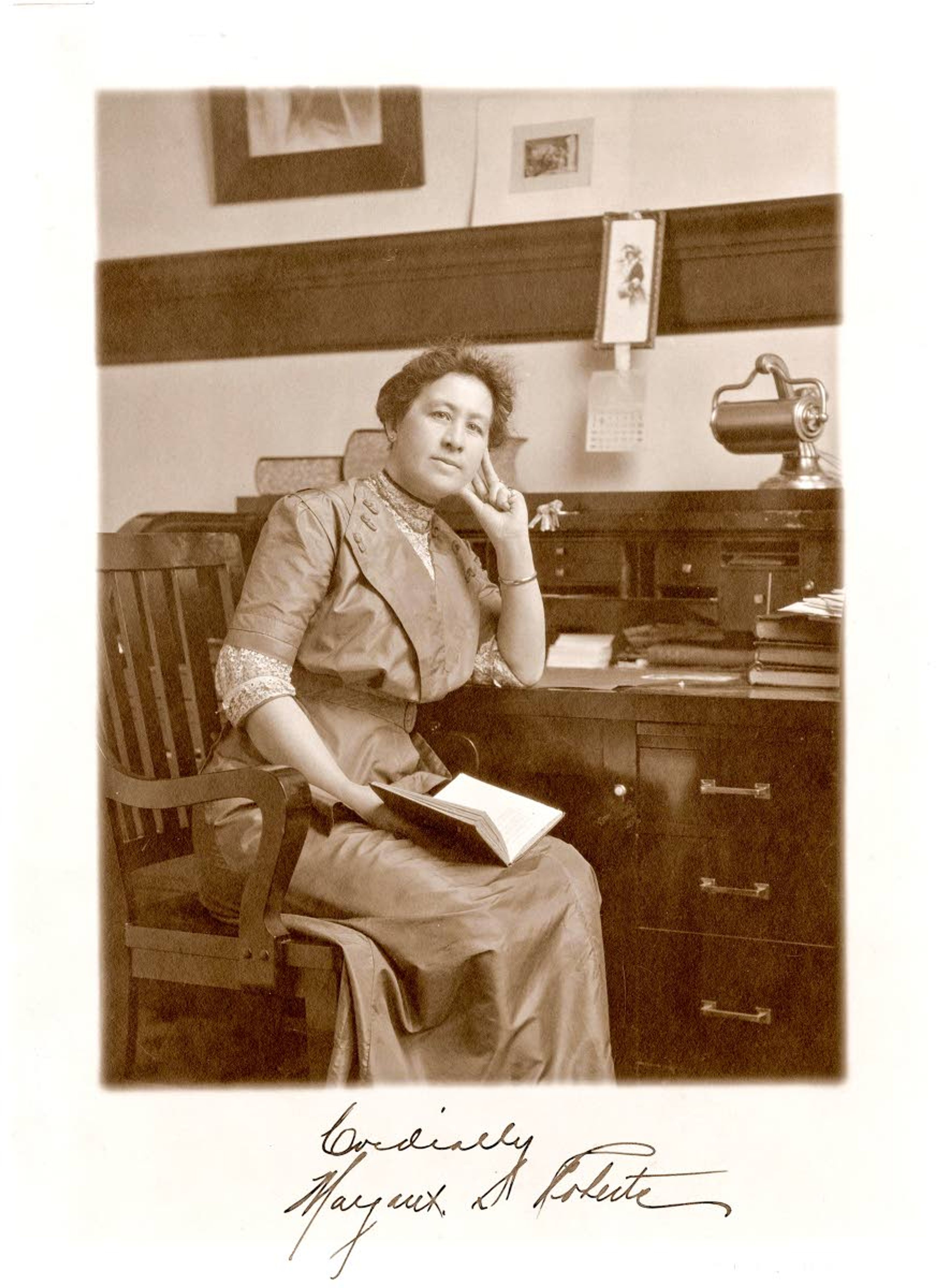

Abigail Scott Duniway believed women’s suffrage was a right. Her husband got into debt in Oregon and was injured in an accident. She started a boarding school, a shop and later, in Portland, she started a newspaper devoted to the issue of women’s suffrage, Hein said.

“She had to figure out how to support her family,” Hein said.

Dunaway gave speeches around the country and in 1887 she moved to Custer County, Idaho. There were other women in Idaho advocating for women’s suffrage such as Carrie F. Young, Idaho’s first woman lawyer and Rebecca Mitchell from Idaho Falls, who fought for suffrage and prohibition, Hein said.

In Idaho, mining communities were against women’s suffrage because of the close association between the issues of women’s suffrage and the temperance movement that sought to prohibit the production, sale and use of alcohol, Hein said.

The Idaho Equal Suffrage Association was formed in 1895 as the state’s first statewide suffrage club, Hein said.

Idaho’s legislature decided to put the question of women’s suffrage on the 1896 ballot. Women across Idaho and their mail allies went to work in the summer to ensure passage in November.

“They ran an amazing campaign, a grassroots campaign, that was especially amazing for people who had no experience doing that,” University of Idaho emeritus professor of history Katherine Aiken said. “It was outside their comfort zone in a lot of ways.”

Women traveled from all over the state to a women’s suffrage conference in Boise, which was no small feat in 1896. Women caught trains through Montana or Washington to Boise or they rode a horse for long distances across Idaho, Aiken said.

“It was amazing how women advocated for themselves in 1896,” Aiken said. “Most of them had never run a meeting before. They had to rent halls, they raised the money for the campaign, they had people at almost every polling place in 1896. they sent letters to ministers.”

When the vote came in November, 12,126 were in favor and 6,282 were against women’s suffrage. The measure passed, but it was challenged in the courts because there were less people voting on the issue of women’s suffrage than other questions on the ballot, Hein said.

Other questions on the ballot received 29,000 votes to women’s suffrage receiving a little more than 18,000 votes. William Borah argued the case for women’s suffrage to the Idaho Supreme Court as a pro bono attorney, which was ironic because Borah would oppose the U.S. constitutional amendment for women’s suffrage in the early 20th century, Aiken said.

“He was kind of the hero in 1896,” Aiken said. “But he was opposed to the national amendment and stridently opposed it all the way to the end.”

Aiken said Borah’s opposition mirrored opposition to women’s suffrage in the Southern states. Borah did not want African American women to get the right to vote.

The Idaho Supreme Court ruled on Dec. 11, 1896 that a non vote on a question on the ballot does not equal a no vote, Hein said.

Women had succeeded in Idaho. A year later, voters elected three women to the Idaho Legislature from Rathdrum, Idaho City and Boise, Hein said.

In the end, Idaho proved to be a leader in the women’s suffrage movement, but only for white women. The women’s suffrage movement in the Gem State in the 1890s did not include women of color, Aiken said.

Wells may be contacted at mwells@lmtribune.com or (208) 848-2275.