OPINION: The acorn lamp and meaning of fake history

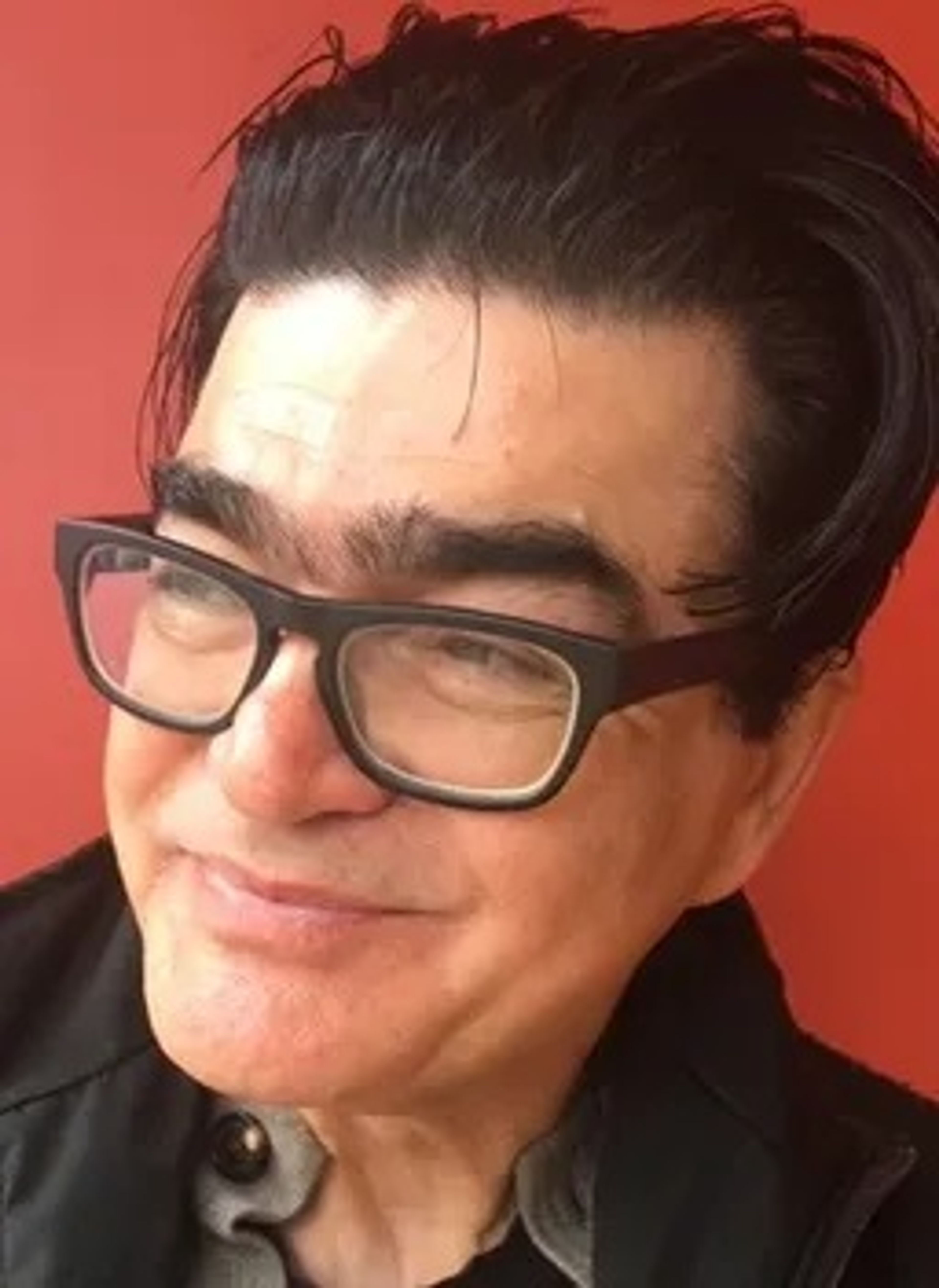

Commentary by Ayad Rahmani

Streetlamps come in different shapes and sizes. The selection is quite large. Pullman chose a specific one for its recent renovation project in downtown. Let’s take a look and figure out what it means.

It is composed of a column and a lens, both harking back to a time before the modern when ornament and classical orders still represented fidelity to moral values related to either God, cosmos, or some other social contract.

The column is Greek and marked as such by a distinct flared-out base, a shaft featuring flutes (vertical indentations) and a flowery capital designed, in this case, to receive the lens atop of that, which features an expression akin to an acorn. Why an acorn, no one really knows, but according to the manufacturer it is likely because it “is evocative of nature and classical design elements, often associated with strength, growth, and sustainability.” But also “an era when gas and early electric lighting became widely adopted in urban environments.”

Fair enough, but what should we make of a design that willfully erases at least about 200 years of history? Since the Greeks and gas lighting, there have come about major changes, in technology, social reform, urban planning and so much more. Since then, we have ended slavery, invented the elevator, penicillin, the computer, Prozac, the internet, the iPhone and now artificial intelligence. Why this intentional and self-imposed amnesia?

One answer may come in the form of context, namely that we live in a setting whose history is everywhere visible, in well-preserved buildings, parks and monuments. No matter where you look you see old facades, rich in detail and ornament, classical motifs and deep expressions of structural honesty. To go through them is to relive precious memories of family and friends who may have shopped there, bought Johnny’s first bicycle, or secured a loan for a house up the hill. All would have been well and wonderful had that been true. But it is not. Pick up a photo from the ‘50s and ‘60s, and you will see many beautiful buildings that have since then been erased and replaced with either nothing or buildings that resemble nothing of the past.

Even as recent as few years back, when Evolve came around and took over the Pullman site on which it sits, the same tragedy happened. In that location there was a midcentury modernist bank building, which, while bland in one sense, was profound in another, highly ethical in its manner of structural and spatial clarity and indeed integrity. Overnight it was gone, without the mere effort to stop and think about what it meant. Very sad.

And yet even more recently than that the same story struck again, this time as related to the Moose Lodge building on Kamiaken Street, a tired box for sure but one that stood nobly on its block and held its corner strongly and graciously. It may not have had deep symbolic values, but it did place on exhibit genuinely old bricks, windows, sills and so on, and not fake ones.

Clearly, we don’t hold history in high esteem, or if we do, only in sentiment but not in action. Clearly, we don’t care to spend the extra effort to find the resources to preserve old structures. At the first open wallet, we bow and take the nearest sledgehammer to existing walls. Which is fine, but then why do we go the extra mile to put up histories that never existed. When did Pullman have acorn lamps or Greek columns? Why do we take down genuine history in favor of fake history?

Perhaps the answer has less to do with the love of history and more with the fear of appearing rootless. Without parents or community, or a number of other agents of anchor, we do risk looking aimless and lost, perhaps sad and threatening. Which wouldn’t be too bad if the problem did not also mean living without meaningful relations. Who wants that and in remedy fake signs of belonging are erected, like Greek columns and acorn lamps?

The fear makes sense, not least because over the years Pullman never formed a firm commitment to either rugged capitalism or aesthetic and moral values, but instead wavered between the two, with results finding expressions in a built environment that lacks a sense of history, identity and culture. No doubt the city cared for quality design and lustily trained its sights on towns elsewhere wishing it could transplant them here, but it never instituted the political itinerary by which it can authentically accomplish as much. So as long as building plans met basic safety standards, zoning and planning codes, they were good to go.

The fakeness does not hit you with a ton or force until you turn the corner on Grand Avenue and look up. There the Greek-acorn lamp posts vanish in favor of industrial lights, towering over the street and commanding a different form of recognition altogether, more military than old small town. You can’t help feeling duped and like the end of a day spent at Disney, you must exit the gates and face reality all over again.

Rahmani is a professor of architecture at Washington State University where he teaches courses in design and theory.